Elizabeth Harrower died a legend despite 40 years of literary exile

Patrick White urged Elizabeth Harrower to write another masterpiece novel but the author was ‘stubborn’ to the end.

Elizabeth Harrower had not one but two outstanding literary careers in her lifetime. In the 1960s, she was feted as the new young voice of Australian letters, taken up by Patrick White, Kylie Tennant and others as she won accolades for her 1966 novel, The Watch Tower. More than 40 years later, she was again the talk of the publishing world as the republication of her work fascinated another generation of readers.

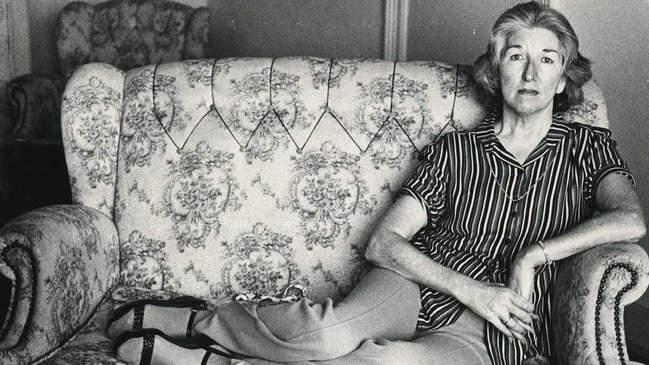

In between, Harrower, a private though not shy woman lived quietly on Sydney’s North Shore having in effect mothballed her trusty typewriter in the 1970s and stopped writing.

But for the enthusiasm of Melbourne publisher Michael Heyward, who championed her revival from around 2012, Harrower, who died on Tuesday at the age of 92, would have been scarcely read or remembered.

Yet she was one of our finest writers – modern, psychological, intelligent with a distinctive style and the capacity to create compelling narratives tackling complex subjects and ideas. Her oeuvre was necessarily small, given the decades when she did not write, but her five books are excellent, with two or three considered masterpieces. Her short stories, emotionally restrained but clear in their vision, are equally good. Her work shares what one critic called “the relentless desire to tell the hard truth” of the writing of the late American literary giant Philip Roth.

In 2014, The New Yorker literary critic James Wood said her writing was “witty, desolate, truth-seeking and completely polished”.

Her interest in the exercise of power in human interactions makes Harrower one of Australia’s most psychological novelists, compared often with her friend, Christina Stead. Her intuition about human motivation and action was superb.

In 2012, when she was 84, she told this writer: “I’ve understood more than I want to understand sometimes, and this is why not everyone is going to like the books because sometimes they tell you things you don’t want to know. I am not sure about a lot of things, but there are things I know that I would never, ever let anyone contradict.”

Harrower, as that comment suggests, was uncompromising when it came to her work.

As an expat, she went hungry and suffered through cold London flats in her 20s and 30s as she pounded out her first three novels, Down in the City (1957); The Long Prospect (1958) and The Catherine Wheel (1960), and was similarly disciplined in Sydney when she wrote The Watch Tower (1966).

But her resolve, indeed her stubborn streak, was best exhibited in 1971 when she refused to allow publication of her fifth book, In Certain Circles, because she felt it wasn’t good enough. Soon after, she stopped writing altogether.

By the time she was “rediscovered” by Text in 2012, Harrower was living in a simple, sunny high-rise apartment at Cremorne on Sydney’s North Shore with sweeping views of the harbour. A slim, youthful, tall woman she had a close circle of friends, many of whom were decades younger and included Heyward and his wife and Text editor, Penny Hueston, although Harrower lamented the deaths of the older writers who had sustained her earlier years.

Harrower always claimed she had not read her books since the 50s and 60s but she was certain that they would be republished after her death.

In 2012 she told this writer: “I thought they were worth finding and I thought someone would probably find them.”

When they were reprinted and the manuscript for In Certain Circles dusted off from the National Library archive and published for the first time, Harrower enjoyed the attention and accolades.

“I was stunned,” she said. “Friends have enjoyed it in a way more than me. I’ve been showered with compliments. I think, ‘what’s going on?’. I am pleased.”

Elizabeth Harrower was born on February 8, 1928, the only child of the marriage of Margaret Hughes, a 19-year-old woman of Scots descent, and a Newcastle railway worker, Francis Hastings Harrower. By 1935, the marriage was over and five years later the couple were divorced. Harrower spoke little of this time but it scorched her early years.

In her 80s, she said: “All I can say is that I was a divorced child. I was the only divorced child really. It was just unheard of (in the 30s and 40s) and children can be very, very mean to other children if they are not exactly identical. Very mean.”

After her parents separated she and her mother lived with her maternal grandmother in Newcastle before returning to Sydney when Elizabeth was about 11. It is impossible to read The Long Prospect without seeing the connections between that fraught childhood and the story of the young girl, Emily, forced to live with her grandmother in Newcastle while her mother works in Sydney. Harrower denied the novel was an account of her own “turbulent” childhood but told an interviewer in 1980 that “you would have to say that the emotional truth is there in all of the books”.

She was an intense child and from an early age a reader and a writer: “I was a great letter writer from the very early years. I used to see the troop trains (during World War II) and I wrote to soldiers. I had a natural inclination to put things on paper, to anyone – to people I knew and didn’t know.”

She went to work in the city after school (university then was for the children of “judges and specialists”, she would later say) but, hungry for knowledge and experience, the young woman read her way through the Sydney City Library, recalling “there was nothing anyone could mention that I hadn’t read”, before heading for Scotland, and then London in 1951 at the age of 23.

She went to the UK intending to study psychology but wound up in London, working clerical jobs and living in rooming houses as she wrote feverishly. She was captivated by the politics of the period, marching against the bomb, enthralled by Labour leader Clement Attlee. Always fascinated by current events and politics, she was a “print junkie” who devoured The Guardian and The Observer, and stood firmly on the left. (Back in Australia in the 1970s, she was thrilled by Gough Whitlam’s ascension and joined the ALP.)

By 1959 she had published two novels that were well received but made little money. Back in Sydney that year, she deliberately took a low-level clerical job at the ABC that would allow her to write and avoid being sidetracked into a career. She left the ABC after a year and in 1960 her third novel, The Catherine Wheel – the only one set in London – was published.

In her 80s she would reflect on her ambition to be a writer: “I was not in a literary milieu in London. It is hard for people to imagine what an unlikely thing it was for anyone to do. Writers didn’t exist, especially not women writers. I lived dangerously, I did without things. I was actually hungry.”

In the 1960s, however, Sydney’s small but influential literary circle embraced the young woman. Writer Kylie Tennant introduced her to Patrick White and his partner, Manoly Lascaris, when they lived at Castle Hill on Sydney’s outskirts and Harrower would later be a regular visitor to the couple’s grand home off Sydney’s Centennial Park. Christina Stead, Bill Cantwell, Jessica Anderson, Richard Hall, Judah Waten and Cynthia and Sid Nolan were part of her circle. In these years she worked in Macmillan’s showrooms in Pitt Street and rented all around Sydney and Kings Cross as she continued to write.

In 1966 when The Watch Tower was published, Patrick White argued it should win the Miles Franklin, but Harrower would be bitterly disappointed when she missed out. The next few years were difficult – she accepted an Australia Council for the Arts grant to write In Certain Circles but was uncomfortable with the process and the result. She was devastated by her mother’s death in 1971 and that same year blocked publication of the book, feeling it was “just one of those dead books” that should not be published.

She wrote a few short stories but by 1977 when her last short story, A Few Days in the Country, was published, her career was over.

Years later, she still wondered what went wrong: “I think I probably made a decision somewhere along the line and I think I was punishing someone [by not writing] … I think I thought: ‘You don’t want me, I don’t want you’.”

She regretted the decision: “I would love to have written more books. I knew more, I should have put more down. I knew more interesting things, I knew more exciting things. I feel guilty because this is something that I can do.”

But writing had been a demanding occupation: “I said to Patrick (White) once that writing a novel was like digging a ditch with your brain. You have to concentrate at such a level.” White was not pleased with her decision to stop writing. “He was so mean to me because I wasn’t writing. He was really, really not happy. But punishment doesn’t work sometimes,” she said in a 2014 interview.

Critics admire Harrower’s deep understanding of human emotions. Publisher Ivor Indyk wrote of her protagonists: “At the heart of their fretfulness is a terrible fear of emptiness, and at moments of awareness, when their emotions run high, and they exhaust themselves with anxiety, it is not the emptiness that triggers their fears, for that is readily filled with emotion, but the emptiness all about them. In short, there is in their restlessness a strong sense that they are doomed. Or damned, rather than doomed – for although theirs is a godless world, you feel the absence of God, or even just a sustaining moral code, most acutely.”

Critics have noted the recurring themes of gender, class and hierarchy in her novels populated by controlling men and women, who James Woods described as “Protestant masochists” who are often unable to break free. Most of Harrower’s work was written before the feminist awakenings of the 70s but readers have long identified with the struggles of her women characters to disentangle themselves from damaging, abusive relationships with the manipulative, misogynistic men in their lives. Novelist Michelle de Kretser says her work “obsessively circles the workings of power within the domestic sphere. Watchfulness, cruelty and the suffering of the innocent feed her work … ”.

Harrower spent decades outside the literary spotlight but her final years were filled with attention and excitement. In Certain Circles won the Voss Literary Prize in 2015, and was short-listed for the Miles Franklin and the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards in 2015, and Harrower was in demand for literary events. In 2017, she was driven by friends to Adelaide to attend the Writers’ Week dedicated to her and her work. (She had made the same road trip almost 60 years earlier to attend the first Writers’ Week in 1960.) There were academic surveys of her work including a 2017 collection of critical essays, Elizabeth Harrower: Critical Essays, edited by Elizabeth McMahon and Brigitta Olubas, was published by Sydney University Press.

Harrower never married and said she never wanted children. In 2012 she remarked: “I am terribly surprised to be the age that I am. I am as lively as a cricket, as lively as I ever was … the world is so beautiful, so interesting that you don’t want to leave it. It is a shame because you feel you have just grown up and you are ready for anything.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout