A China book we don’t really need

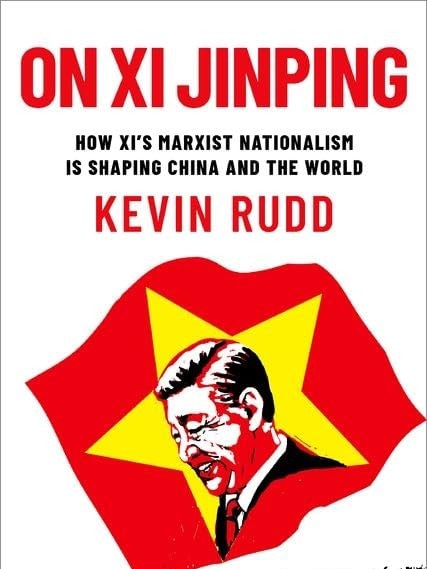

His new book On Xi Jinping begs one obvious question: Why on earth did Kevin Rudd think this was a good idea?

The literature on China’s rise and the neo-totalitarian regime of Xi Jinping is voluminous. Some of it is very good. The debates concerning crucial aspects of it are important and analytically challenging.

Kevin Rudd has added to all this an excruciatingly detailed exegesis of the propaganda and policy proclamations under Xi Jinping and his recent predecessors.

Those professionals who follow the subject are aware of what Xi has been doing: reversing the political and economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping (or more precisely his liberal acolytes), abandoning his hide and bide approach to the display or exercise of Chinese hard power and doubling down on censorship, indoctrination, surveillance and propaganda, while rejecting any possibility of democratic liberalization.

John Fitzgerald’s Cadre Country: How China Became the Chinese Communist Party (UNSW Press, 2022), Steve Tsang and Olivia Cheung’s The Political Thought of Xi Jinping (Oxford University Press, 2024) and Chun Han Won’s Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China’s Superpower Future (Corsair, 2023) all cover the terrain.

Michael Sheridan’s Red Emperor: Xi Jinping and His New China (Headline, 2024) and Josh Chin and Liza Lin’s Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control (St Martin’s Press, New York, 2022) are also perfectly adequate guides, especially when taken together with the others. And these are the tip of an iceberg of commentary, in books and journals.

What did Rudd think he could add to this? Why, having been prime minister, then foreign minister of this country, then first head of the Asia Society Policy Institute in New York, from 2014, did he think that this account of every step in Xi’s ideological evolution would be a good use of his time, or something others would value?

Well, to be fair, he undertook his study of Xi as a DPhil at Jesus College, Oxford University, from 2017, before any of the above books had been published. He presumably thought this would enable him to at least get his own thinking about the Chinese dictator clear.

Moreover, the increasingly assertive stance of Xi in world affairs makes close analysis of how he thinks important. Everyone from politicians to corporate leaders to intelligence analysts and university students does need to grasp what Xi is doing. But what Rudd has offered them is almost indigestibly dense.

Publishing the updated doctoral dissertation in 2024, also, must have taken a good deal of time, during 2023-24, out of his busy schedule as Australia’s ambassador to the United States, at a critical stage in Australia’s relations with its great and powerful, but internally fractured ally.

It’s rather as if George Kennan, instead of writing his famous “Long Telegram” from Moscow, in 1946, had written a six hundred page tome On Stalin and published it under his own name. It’s strange, on the face of it.

That said, if you have the patience or the perceived need to trawl through the book’s sixteen chapters, or even, as Rudd himself suggests, just the first three and the final three, you will encounter something truly remarkable: a minutely documented account, down to tabulated enumeration of the uses of “banner words” or key phrases in Party documents, the Party’s propaganda outlets and official speeches; the parsing of planning documents, the painstaking definition of terms such as nationalism, ideology, worldview, Marxism and Leninism – all in order to show that Xi has moved China from a relatively market-oriented economy to a highly mercantilist and state-dominated one and from a cautious to an ambitious military and geopolitical stance.

Yet anyone who has been paying attention for the past few decades has been able to follow all this quite readily. In any case, Rudd nowhere seriously probes beneath the rhetorical surface to seek out the tensions within China’s intelligentsia over the path on which the authoritarian dictator has insisted on taking the country. Yet even in the terrifying Maoist years that was standard practice, not least by Rudd’s revered mentor Pierre Ryckmans, to whose memory he dedicates the book.

Fred Smith, singer songwriter, wrote and recorded a wonderful set of songs about the tragic civil war in Afghanistan some years ago, called The Dust of Uruzgan. It includes a song called “Woman in a War”, the refrain of which goes “Pay no heed what people say/Notice only what they do”. If we did little more than observe closely what Xi was doing, over the past ten to twelve years, we were able to understand what was happening. It’s not clear that Rudd’s textual and terminological exegesis adds any real value.

Chin and Lin’s Surveillance State is all about what Xi has done to China and why. It pivots on the pioneering, Orwellian vision of a Chinese scientist named Qian Xuesen, decades ago, that a high tech surveillance state was possible. His name nowhere appears in Rudd’s book. Nor do the Silicon Valley and Chinese companies that have created this state for Xi, under his close direction. Nor do the names of those Party figures, starting with Hu Yaobang and his circle, in the 1980s, who warned against China sticking to a “dragon culture” receive more than passing mention, if at all.

Make no mistake, On Xi Jinping is a formidable intellectual achievement. It must have taken Rudd endless patient hours to pull all this together, and include seventy entries under his own name in the Bibliography – more than any other author. It’s just not obvious that this served much purpose, or was the best use of Rudd’s time.

Perhaps the DPhil and book feel satisfying to Rudd, given his ANU honours thesis on Wei Jingsheng decades ago, and his work, in 1984-85, as Second, then First Secretary in our Embassy in Beijing, analysing Politburo politics, economic reform, arms control and human rights for then Ambassador Ross Garnaut.

Hu Yaobang was then at his height and liberal reform was in the air. In this book, Hu receives only three cursory mentions. Yet his thinking was China’s last best hope.

On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism Is Shaping China and the World

Paul Monk is a Fellow of the Institute for Law and Strategy (London and New York), was head of the China desk in the Defence Intelligence Organization, and is the author of a dozen books, including Thunder From the Silent Zone: Rethinking China (2nd edition, 2023) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout