Beauty from the ugly truth for Edgar Degas

DEGAS'S popularity today masks the sometimes brutal realism of his work.

Degas: Master of French Art. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Until March 22. Closed December 25.

EDGAR Degas once declared that he wanted to be illustrious and unknown. He had his wish: he is clearly one of the great artists of the 19th century, yet the man remains elusive. What is really remarkable, however, is the degree to which his work is simply misunderstood: it is not unusual to hear people exclaiming at the beauty of his ballet dancers, or even at the statue of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, considered shockingly ugly by contemporary viewers. Reproductions of his ballet paintings hang in dance schools and girls' bedrooms, even though the young women Degas painted were often plain, always uneducated and mostly destined to supplement their earnings through prostitution.

There is much more to the pictures than this, of course, but the popularity of Degas owes a lot to the superficial way we generally look at paintings. The new exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia is a welcome opportunity not only to admire the work of a great master, but also to consider the various facets of his poetic world and the diversity of the media and genres that he employed.

It is a fine achievement, including important paintings as well as works on paper and sculptures, and is a credit to the curator, Jane Kinsman. If there is anything to be regretted -- apart from the absence of the late pastel bathers, which apparently could not travel for conservation reasons -- it is that the last section is titled Towards Abstraction, which implies an unwarranted modernist teleology, an assumption that art is moving inexorably towards the illusory consummation of the abstract.

This is untrue in general and more so in relation to Degas. Similarly the catalogue cover cannot help referring to the artist as radical and opposing him to "conservative traditions". There should be a moratorium on the use of such expressions, which have become the most arid of cliches.

And if any modern artist conspicuously refuses to be pinned to these dreary but seemingly obligatory poles, it is Degas. He was not an avant-gardist searching for ways to look innovative and surprising; he was a classicist and an admirer of tradition whose pursuit of truth led him to make real, not gratuitous, experiments, and whose academic training allowed him to take shortcuts that would have been unavailable to others.

Degas was born into a wealthy family and went to the best school in Paris, though many years of his adult life were later overshadowed by the financial catastrophe of his father and brother. His grandfather Hilaire was a very rich banker established in Naples, while other members of his family were in the cotton business in New Orleans.

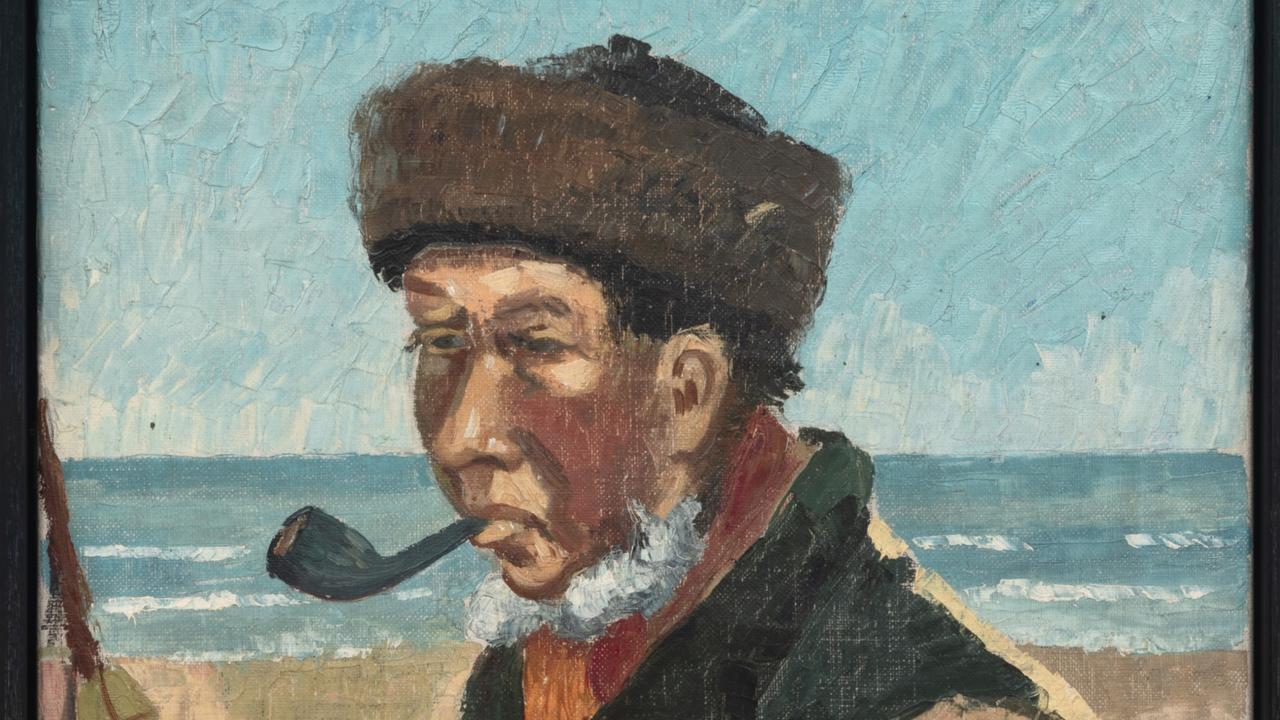

Although the boy was meant to study law, his father Auguste, who was more interested in music than banking, allowed him to study art instead. The amazing talent of the young man is evident in the two self-portraits at the beginning of the exhibition, one in oils and the other in red chalk. These works are as astonishingly sophisticated in their psychology as they are refined in their mastery of the materials: there is an acute sense of penetrating curiosity held back by reticence, pride, even a kind of dandyism.

One can see already much of the character of a man who was private, proud, lonely, self-centred and obsessed with his work, who never married and may or may not ever have had a lover. And yet he was exquisitely sensitive to others and to their personality, character and moods. This is what made him a great portraitist. Whether in the gentle and refined features of Helene Hertel or those of his sister Marguerite -- respectively in a pencil drawing and an etching -- or later in the gross and stupid faces of tired prostitutes in a brothel, Degas had an almost miraculous capacity to read the soul of his subject and to embody it in graphic form.

There is hardly a better illustration of the principle that the thinking of the artist is inseparable from the work of the hand; Degas could not have articulated or even perhaps perceived what he did in any other way.

One of his most elaborate works of portraiture is a group of his New Orleans family, A Cotton Office in New Orleans (1873). The apparently casual composition is very carefully constructed; it centres around the foreground figure of Degas's uncle Michel Musson, in Vermeer-like concentration on a hank of cotton -- such expertise being at the heart of the enterprise -- while behind him the artist's rather feckless brother Rene lounges reading the paper. Details such as the old man's hands reveal the depth of the skill Degas acquired through his assiduous study of the much-maligned conservative traditions, but also the lightness with which he employs his virtuosity.

Such refinement and attachment to clarity distinguish Degas from the impressionists with whom he was to exhibit for some years. It particularly contrasts with the ham-fistedness of the young Cezanne around this time (think of Afternoon in Naples, at the NGA). Cezanne would of course evolve into one of the greatest of modern painters, and Degas later collected his works, but he was never at ease with the human figure.

Equally remarkable in this painting is the mastery of colour and tone, built around the cool green of the walls, a colour that Degas loved all his life, and the warm browns of the floor and furniture; there are touches of pink and blue in the foreground for variety. These mid-tones are framed, as it were, by the strong black of the suits and the white of the cotton (the mass of soft cotton fibre on the table is nicely echoed in the cotton shirt sleeve of the clerk on the right).

Compositionally, what gives the Cotton Office a look of unexpected realism is the combination of cropping at the edges (possibly an effect inspired by photography, though cropping was extensively used in the mannerist painters Degas had seen in Florence) and a view from slightly above, which makes the floor seem to tip upwards (again, oddly enough, an effect common in 15th-century Flemish painting).

In both these respects, the most telling comparison is with The Bellelli Family (1859-60), in which the figures are contained by the composition and seen frontally. Although this work is not in the exhibition, the same vision of the world is implied in the study of the two Bellelli girls. Ever since the invention of perspective, the underlying assumption has been that the viewer's sightline is horizontal, parallel to the ground. The rising floors of the Flemish paintings are there because perspective theory had not yet been assimilated in the north.

In Degas's case, it is an aesthetic choice to break with the perspectival model of objective vision and evoke a direct and personal encounter. This is an effect he continues to use for the rest of his life.

The use of strong blacks and whites -- visible also in At the Races (1869) -- is later abandoned in favour of a more continuous tonal range, with less sharply defined extremes, in The Racecourse (1876-87). Horses were a favourite subject, as they had been for Gericault; but the contrast is instructive. While Gericault's horses are embodiments of romantic sensibility, expressions of irresistible vital force, those of Degas are nervous, highly strung and moody.

But women are Degas's quintessential subject. The nude in art, which had been predominantly male from the renaissance, when figures were part of narrative paintings, became mainly female in the 19th century, as artists suffered from a lack of meaningful subjects. Ingres had ended up painting bathers, which are essentially unemployed figures; so would Cezanne. Degas encountered the same problem as Ingres, whom he admired so much: having tried to paint important narrative pictures, he eventually fell back on the female nude.

The study of the figure, fundamental to the Western tradition and its pedagogy, served the needs of a particular genre, that of history painting; since the decline of that genre, artists have tried to put the nude to work in other genres. Thus Cezanne turns his figures into parts of a landscape, Lucian Freud treats them as still lifes, and Degas resorts to the genre of animal painting; it has often been observed that he watches his bathing women in the same way one would watch a cat cleaning itself.

Naturally he has been accused of misogyny, but this is clearly simplistic. We have already seen that both beauty and ugliness, refinement and stupidity can be found in his images of women. What is probably more to the point is that he sees women as essentially intuitive and instinctive in their natures; the wilfulness and rationality of men are of less interest to him.

Thus his monotypes of the pensionnaires in brothels are dispassionate but inexhaustibly curious observations of creatures who have almost no inner life, but who alternate between comatose boredom and sudden avid alertness when a client walks in. These rapid, instantaneous and unique images are like an experiment in observing the most elementary level of human responsiveness. But there is no puritanical disapproval, and the figures of washerwomen (often retired or part-time prostitutes) are sympathetic, if by sympathy we mean feeling for and understanding of their experience, rather than mawkish sentiment or moralising.

The ballerinas are, in the end, his central motif. Degas's dancers are not pretty middle-class girls going to ballet class. They are scrawny little proletarians whose talent may allow them to escape poverty and drudgery in a sweatshop for a while but who will almost inevitably be the paid mistresses of various male admirers.

Degas is fascinated by the way these girls, who are seldom beautiful in themselves, can be made beautiful by the arts of choreography and music; hence the central role of the ballet master Perrot in The Dance Class (1873-76). But he never lets us forget, if we look closely, the unpromising nature of the raw material; in the late Dancer with Bouquets (1895-1900), he does not attempt to disguise the ugly rictus of the girl's mouth. In particular, Degas is struck by the contrast between the elegant and artificial attitudes instilled by the choreographer, and the instinctive, involuntary actions of a girl who stretches her aching limbs or, as in The Dance Class, scratches herself.

The famous statue Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, originally in wax (1880-81) and represented in the exhibition by one of the later bronze versions, epitomises the paradox that fascinates Degas. The girl herself is not at all beautiful; indeed Degas was specifically interested in the ugliness of her features and even of her figure, as is made clear by the nude version included in the show, with its pot belly and scrawny hips. The key to the work is that the girl is simultaneously stretching and standing in fourth position; she embodies both involuntary action and learned elegance.

The final work is beautiful, though the subject was not, and the beauty is Degas's achievement, just as the painted dancers are beautiful because of his drawing, colour, composition and poetic conception. The magical transformation that takes place on stage is replaced with the magic of art, in which truth becomes beauty.