Archibald Prize finalists revealed at the Art Gallery of NSW

The strongest portraits in the Archibald lineup have an eccentric charm or reveal something of the sitter’s personality.

The extreme disparity between portraits selected for the Archibald Prize in recent years recalls the old saying about a camel being a horse designed by a committee – but it’s actually much worse than that.

If anything, it reminds me of the appalling tourists I saw in Cyprus a few years ago – bloated and sunburnt Putin loyalists – piling a whole breakfast smorgasbord on to a single plate, with chocolate cake balanced on fried eggs and bacon.

The distasteful mess that results in the portrait prize is entirely the fault of the trustees of the Art Gallery of NSW, who select and judge the pictures.

There were 816 portraits submitted for the Archibald this year, and it is clear that anyone with the slightest discrimination could reduce these to a decent exhibition, or even several.

We know this because so many good pictures, knocked back by the trustees, turn up in other shows such as the Salon des refuses or the Portia Geach, both held at the S.H. Ervin Gallery.

Instead, the trustees deliberately seek disparity and cacophony; they want the audience to be surprised, titillated and even shocked. Hence the range from coloured-in printouts of photos to real or pastiche outsider art.

At the same time, the gallery – like all institutions these days – is desperate to tick ideological boxes: genderists, racialists and other identitarian narcissists all need to be appeased.

And there are still a few colossal heads, like dinosaurs surviving from another age.

One of the mysteries of the Archibald, incidentally, is why people who should know better allow themselves to be painted by certain artists. Painters look for well-known figures to be sitters, but allowing an artist to paint you is an implicit endorsement and thus reflects on your own judgment.

Among the few paintings that can be taken seriously, Keith Burt’s picture of Bridie Gillman is sensitive and interestingly composed, although the palette is a bit cool and lifeless, contrasting with Tsering Hannaford’s adjacent picture, which is dominated by warm colours.

Both are very talented painters, but in one case the effect is a little bloodless, in the other rather suffocating. Just as the balance of tone – of lights and darks – gives vitality to a painting, so does the energetic interplay of warm and cool colours.

Ann Cape has a good portrait of her fellow painter Euan MacLeod which, unlike some other pictures, shows that she has spent time with her sitter and has come to know him.

Robert Malherbe’s portrait of Dana Rayson is intimate, inward and intense though at the same time distant and dreamy.

Lewis Miller’s Deborah Conway is striking and authentic although it could, in the end, have been more effective as a head-and-shoulders picture than as a seated full-length with large areas left unpainted, reducing the face to a tiny area of the pictorial surface.

One of the best pictures in the show is a little self-portrait by Wendy Sharpe in a found antique frame. Sharpe has done a lot of work with found and antique frames recently and, apart from the many interesting associations they bring with them, they also generally enforce a smaller scale than is usual in oversized commercial art today.

Sharpe is a talented artist, and the painting benefits from the discipline of the small frame, creating a moving and intense image of herself emerging from the shadows, with a dreamlike apparition over her shoulder.

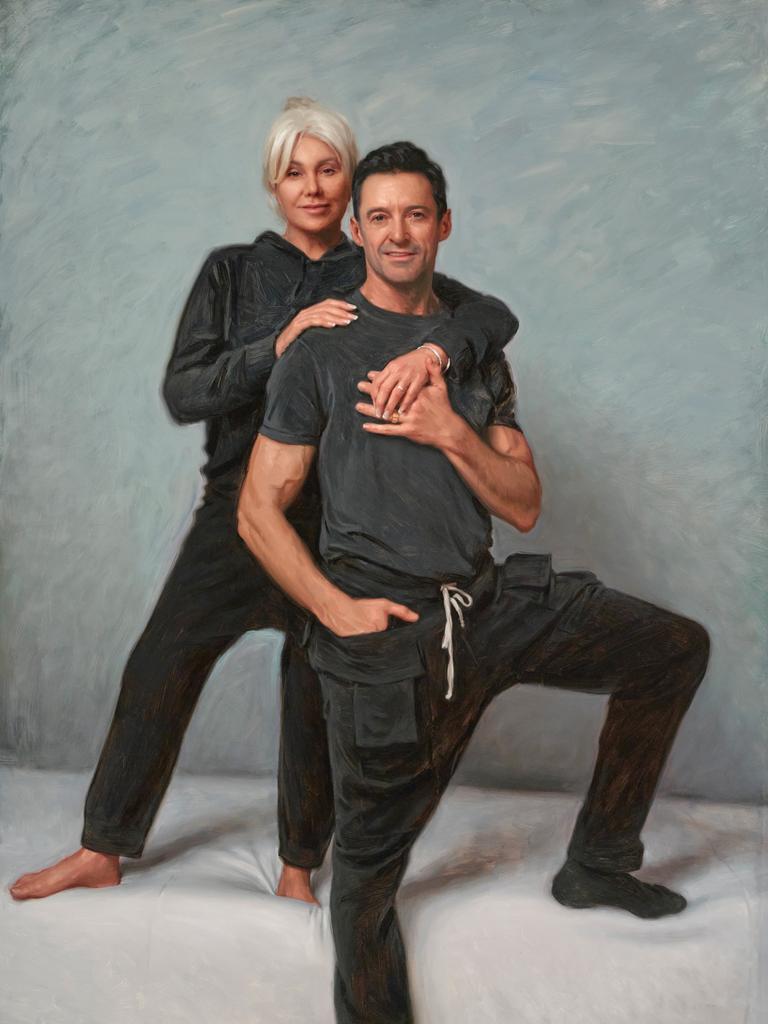

A few other artists deserve a mention, including Paul Newton (he has painted actors Hugh Jackman and Deborra-Lee Furness) and Jude Rae (inventor Saul Griffith).

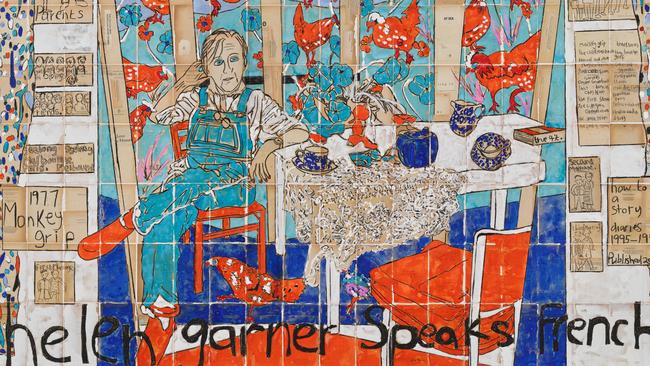

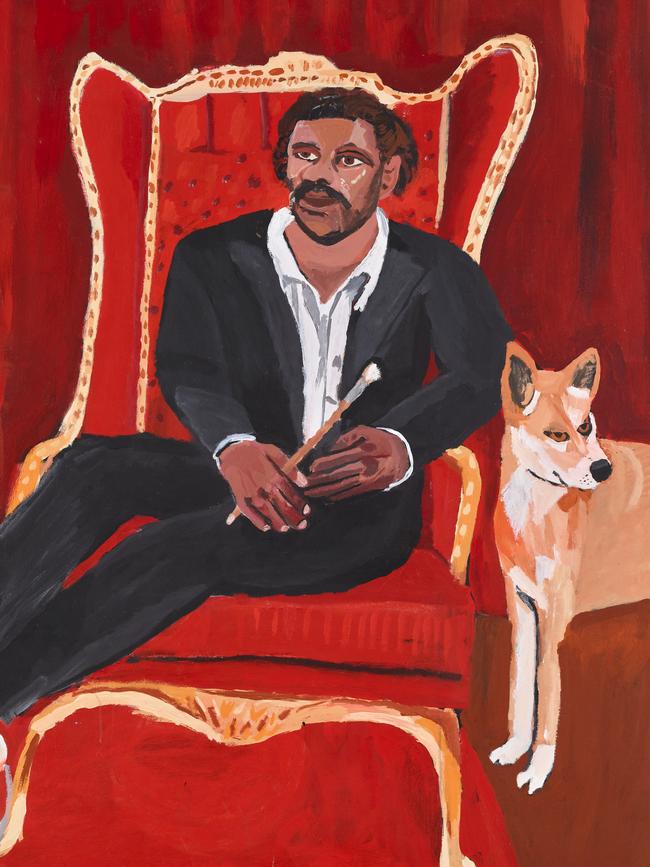

And there are some others who have a certain eccentric or quirky charm, including Noel McKenna, even though he almost omits his subject’s face (art collector Patrick Corrigan), Vincent Namatjira for his self-portrait with a dingo, Katherine Hattam with Helen Garner, or Yoshio Honjo’s portrait of Yumi Stymes in imitation of ukiyoe woodblock prints.

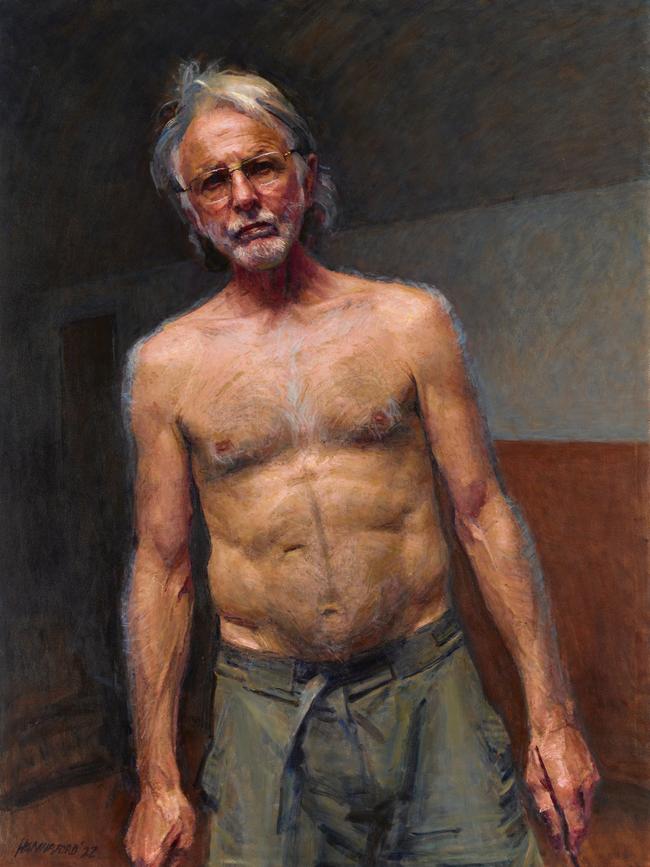

If there is one painting that stands out, both for the quality of its painting and for its expressive presence, it is Robert Hannaford’s self-portrait. Hannaford is Australia’s most distinguished professional portrait painter, and has been represented in the Archibald countless times.

If the prize were judged by portrait artists instead of by business people and socialites, he would have won it long ago.

This picture, a statement of his virtuosity, but also his courage and persistence in the face of severe illness, has a conviction that no other picture in this exhibition achieves.

It shows up the paper-thin weakness of most of the other finalists. And it reminds us of the shameful injustice done to Hannaford in 2018 when his fine and moving self-portrait was overlooked in favour of what was, in my view, a work of obvious and embarrassing mediocrity.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout