WHO would have thought it? Just when we had got through an Archibald prize season without the much-anticipated controversy, there was one, after all, in the usually dull Wynne exhibition.

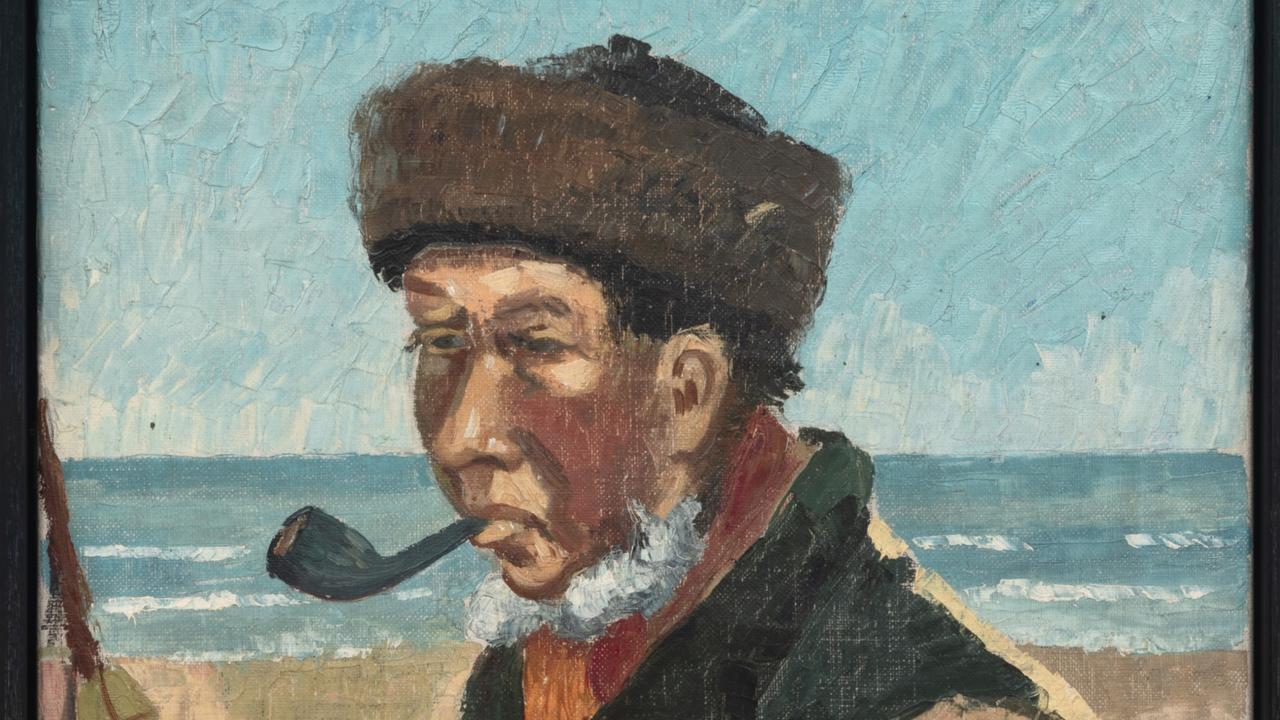

Sam Leach, who created a minor sensation when the Art Gallery of NSW trustees fell in love with his work and awarded him both the Archibald and the Wynne, turns out to have based his landscape composition rather too closely on a 1660 work by an Italianate Dutch painter, Adam Pynacker.

As to the legitimacy of what Leach has done, the matter is both complex and ultimately fairly straightforward.

Because the area is rather unfamiliar to contemporary theory and beset with various fallacies about the nature of art, it is necessary to be clear about the principles.

Most people take it as axiomatic that art has to be original, but they seldom stop to think what that means.

Instead of analysis, we encounter cliches. The most shopworn terms in art writing are innovative, groundbreaking and the like.

The myth of originality has its immediate origin in modernism and a deeper taproot going back to the romantic movement. Anyone who knows much about art or literature, though, is well aware that such activities belong to cultural and technical traditions in which material is constantly borrowed and reconfigured.

Homer, our first author, was already recycling earlier material; artists from the beginning of history to the present have scoured the work of their predecessors for ideas and solutions to problems. It was only the misunderstanding of this by the modernists that allowed the postmodernists to rediscover this fact as though for the first time.

So there is nothing inherently wrong with borrowing from artists of the past. Culture lives through a process of transmission and transformation. What we admire in the work of our predecessors cannot simply be repeated, as academies of all kinds tend to imply; it must be taken and changed in order to continue to live.

This is what is meant by tradition: we accept what we are given by our predecessors, with respect and a sense of responsibility for what has been entrusted to us, but also with boldness and courage. We assimilate it, make it our own, change it where we need to and pass it on to our successors.

Postmodernism did not quite understand this process, because it had inherited the modernist prejudice that the past was dead, and tended to think that art was made from the lifeless remains of older art, missing the point that cultural tradition operates by the giving and receiving of material that is alive and renewed by successive generations.

Of course a number of so-called postmodernists were intuitively cleverer than that.

So what has Leach done? Basically, he has copied a composition by Pynacker on a much reduced scale while omitting the figures, boats and cattle that were part of the original composition, and added various little touches that give the scene a slightly surreal or science-fiction appearance.

The composition is awkward and unbalanced without the figures, which played a central role in its articulation, while some elements, such as the foreground trees, become excessively prominent. The heavy resin coating conceals any painterly sensibility in the surface and makes the picture look illustrative and formulaic.

There are two more serious problems, the first of which is aesthetic and the second ethical.

To begin with the aesthetic, the picture is copied too literally, and in this respect it is closer to the postmodern appropriation of dead material than to the transformation of a living tradition. This is a shame because, from what I can see, Leach is talented and could do better.

The second problem is ethical. There is nothing wrong with quoting as long as you acknowledge it; failing to do so constitutes plagiarism.

As so often, this is ultimately a matter of common sense. It may not be necessary to refer explicitly to a borrowing that everyone will recognise, nor one that is remote or approximate.

But it is always better to err on the side of prudence; in this case the words "after Pynacker" would have sufficed.

As it is, Leach has very closely copied a relatively unfamiliar work, disguising this by reducing the scale and removing its characteristic figures, and has failed to acknowledge this fact while entering an important competition.

The judges, who have to look at many works in a short time, deserved to be properly informed, not ambushed and humiliated, and they would be quite justified in reconsidering their decision.

Christopher Allen is The Australian's national art critic.