Hamish McLachlan: Footy hero Jason McCartney on why he’s a lucky man

Jason McCartney tells Hamish McLachlan how focusing on a return to footy was crucial to his recovery from the Bali bombings.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

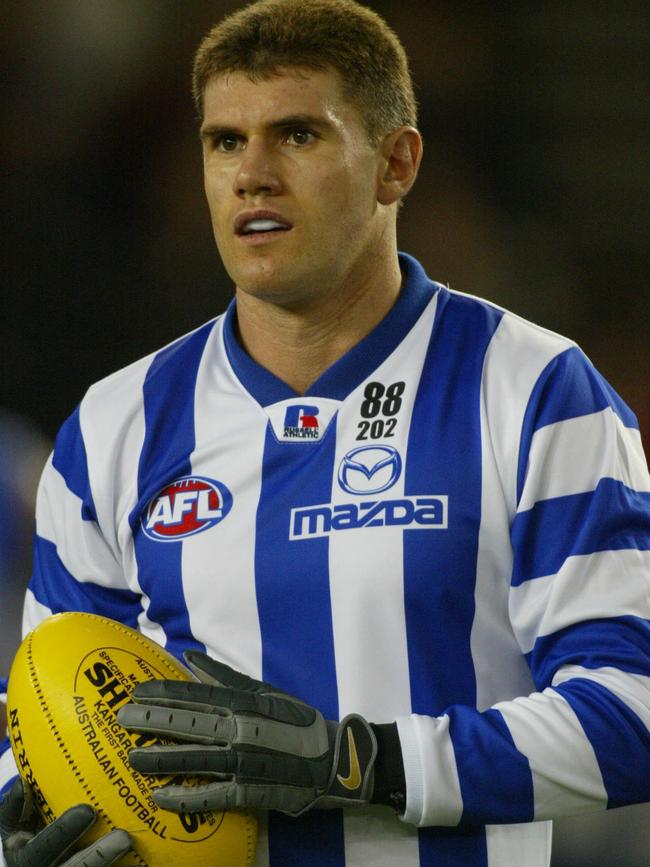

Jason McCartney played 182 games of AFL football for Collingwood, Adelaide and finally North Melbourne. His last game was the most extraordinary. And the most unlikely. It came after a terrorist attack in Bali almost took his life, as it did many of those he was near that night.

HM: Were you a better cricketer or footballer representing Nhill?

JM: Football! I enjoyed my cricket, but football was always where I felt my talent was.

HM: Right-arm quick?

JM: We were all right-arm quicks growing up, weren’t we? I tried to be really quick. It soon takes its toll on your knees and back when you’re playing on the malthoid wickets!

HM: How big a town is Nhill?

JM: Well … the population sign hasn’t changed for 30 years. About 2300.

HM: Most famous Nhill product?

JM: David Flood, Dean Wallis or Adrian Burns I’d say. If you count premierships as success, it’s Wallis with his two. Games wise my career ended up being longer than the other boys, though!

HM: You were hugely talented, but 16 does seem a very young age to be sent to Collingwood.

JM: I laugh when I look back on it now. Having worked in that talent space for the AFL, and at club land, you’re working with kids that are 16 and you can’t help but reflect on the fact that that’s what the draft age was. You think of Tim Watson playing out of Dimboola at 15 – it’s just hard to imagine. It’s a different system now, but it was a huge eye-opener leaving home in 1990 after turning 16 earlier that year. I’d played senior football for a year and a half, so it was a great opportunity to step up in that space. When you work with kids now, and see kids, you wonder how on earth we allowed that.

HM: Were you ready?

JM: I was. I was a bit bigger and more mature than many my age, and the systems we have in place now from a talent development perspective are far greater. We have the NAB League in Victoria, the SANFL in SA and the WAFL in WA, before you push into senior level. We didn’t have those opportunities. Some of my best memories were playing senior footy from 14 to 16 years old in the country.

HM: You arrived at a good time at Collingwood.

JM: They’d just won the premiership, and some of the most famous names in the game were there. The first day I arrived at the club would have been in early December of 1990, and you see the late great Darren Millane, Peter Daicos, Craig Kelly, Michael Christian, Mick McGuane and Gavin Brown. It was quite daunting.

HM: Particularly as an Essendon fan!

JM: A little daunting given I’d spent all of my youth barracking for Essendon, completely idolising the Essendon Football Club, and I’d been cheering for them against the club I was now playing for, a few months beforehand!

HM: Why after four years did you head west to Adelaide?

JM: I’d played a lot of junior football as a forward, but I actually played in the schoolboy’s championships at centre half-back. The best football I played at Collingwood was when Ned did his knee and was out for 12 months. I cemented myself in that position. Ned came back, Michael Christian was playing there, and then we had a great recruit from Fitzroy come in by the name of Gary Pert. I knew my opportunities were limited in that position. I was very familiar with Adelaide as a city, growing up in Nhill, which is halfway between Melbourne and Adelaide. I spent a lot of time over there as a kid, so when they showed some interest, I jumped at that opportunity. When I was playing there early days, I was at centre half-forward again. That wasn’t part of the plan.

HM: You were doing your own list management as a player, just seeing how it was all going to play out, and plotting your own path.

JM: Most definitely. I thought the opportunities would be limited if I stayed at Collingwood. I’d be constantly looking at stats in the SANFL, so I knew all the players coming through. I knew they’d be a pretty good side in time, which proved to be the case.

HM: You can get unlucky. You left Collingwood for Adelaide, and in 1997 you played six games for the Crows, but didn’t make the premiership team. You left, and in ’98 you played in the grand final for North, after leaving the Crows, and lost to them. And then in ’99 when you’d never been in better shape, you got suspended and missed the grand final win for North. It’s a pretty tricky three years.

JM: It was an interesting three years, that’s for sure. In ’97, that was Malcolm Blight’s first year as coach. I only played the first six games. I’d been a regular the previous two years under Robert Shaw. After those first six it saw me on the outer, and I couldn’t get back in. I made the move across to North at the end of that year, and I realised you can be the best side all year and not win it. We were certainly that at North Melbourne in ’98. The Crows just got there again, but they produced on the only day that it counts. To get reported and suspended in ’99, and miss out, was really tough. That’s footy. You move on. And with every little setback I had along the way, the next year I’d come back and have a better year. That premiership eluded me because in 2000 we were beaten in a prelim final by Melbourne, and I never got back to the big dance again in the playing career.

HM: After the ’97 season, was it Denis Pagan who called you?

JM: Denis came over and saw me the week after the 1997 grand final. He’d been in contact throughout the year. At that stage, after only playing the six games, I’d lost a lot of belief. I thought my days were numbered. When Denis showed interest, although it was flattering, he came and saw me at West Lakes after the grand final, which, to be honest, wasn’t an ideal week for a visit!

HM: He turned up at your house?

JM: He did. I’ll never forget, he walked into my place at West Lakes, and he just had this A4 sheet of paper. He handed it to me, and it just had all these points detailing what was good about me. He was the master psychologist, Denis, and he really made an impression. Two weeks later, when the trade period started, I refused the opportunity to head over, and said I was staying. He called back on the final day of the trade period. In the seven years prior, I’d only played 75 games. Whatever it was Denis said, his persistent endeavours, I’m very grateful that I took the opportunity. A one-year contract at the time, to move back to Melbourne and play under Denis at North Melbourne.

HM: You played a lot of football for North and then in 2002, life as you know it got turned upside down in Bali. When you look at your Bali experience, do you look at yourself as being incredibly fortunate, or incredibly unfortunate?

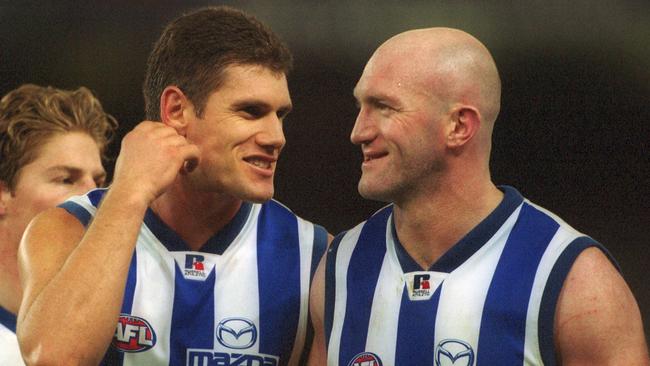

JM: That’s a great question – and one I wrestled with early on. But the answer is overwhelmingly fortunate. Incredibly fortunate, given what actually took place. Unlucky to be involved in something like that, but from the moment it happened, I feel like every step of the way, I was fortunate. I was fortunate that Mick (Martyn) was there and was able to help me get some medical attention. I was fortunate that I ended up back in Melbourne at The Alfred hospital, with great support around me, and very fortunate everything healed pretty well and quickly. I do feel very lucky after being in such a horrific situation.

HM: Do you find it difficult to talk about?

JM: In the early days, I certainly did. It’s easier to talk about it when it’s about yourself. It would be much more difficult if it had happened to one of my sons. It was hard early, but I also felt it was unbelievably beneficial in my whole healing process, mentally and physically.

HM: To talk about it?

JM: Yeah. Being in the environment I was in, you can’t be fronting up in the physical shape I was in and avoid talking about it. It was confronting for the boys, so I addressed it and it was easier to do that, than not.

HM: Take us back to the night of the explosion. You were standing at the bar with Mick when it happened?

JM: We were in Paddy’s Pub. There were two levels, and we were downstairs near the bar, standing with a couple of other mates. We’d only been there 10 or 15 minutes. We had no idea at the time, but where the bomb went off, it was only about five metres from where we were standing. We were incredibly fortunate to make it out alive.

HM: Was it literally five metres from you when it exploded?

JM: Yes. We had no idea at the time, but it all makes sense when you get told what happened. The two things that will live with me forever were the sound, but also the sheer force that I was hit with from the explosion. I’ve never been hit like that before. It was like something you see in a movie.

HM: You thrown across the room?

JM: It knocked me completely off my feet. Thankfully, I was able to turn my back on it, but the force threw me three or four metres across the bar.

HM: How quickly did you recognise what had happened? That it wasn’t a gas bottle or something in the kitchen exploding, but a bombing?

JM: I had no idea – I just didn’t contemplate terrorism.

HM: What did you think?

JM: Everything is rushing through your mind, but it feels like everything is in slow motion. There were people screaming and crying and trying to get to safety and out of the bar. My first thought was that I’d been shot. Then I thought that the boys close by in Hawaiian shirts on a footy trip must have let off some fireworks and I’d been hit by one of those. It wasn’t until the next day that we were alerted to the fact that it was an act of terrorism. That night, when we got to the Sanglah Hospital, to try and keep everyone calm they were talking about a gas explosion at the pub.

HM: Knowing that it clearly wasn’t?

JM: Yep. But they were trying to keep people from being terrified and panicking.

HM: It would have been terrifying chaos.

JM: Mayhem. The flash of the explosion was so bright, I was temporarily blinded too. When my vision did return – and it didn’t take long, but it felt like forever – that’s when I realised that the building was on fire, and worse, people were on fire. Then I looked over my left shoulder and I could see the flames roaring up the back of my shirt, and I realised I was on fire. I dropped and rolled on the ground to try to put it out.

HM: And then I’m told you started helping others?

JM: Like I imagine anyone would do, you just try and help those that need it most. I thought it was Mick who was standing next to me, but it happened to be a girl that was in a group nearby. We couldn’t see anything, but we guided each other 15 or 20 metres to get out of the building. We got two-thirds of the way, and I thought it was my clumsiness, but we stumbled to the ground again. That was the effects of a massive car bomb explosion outside the front of the Sari Club. The terrorists’ plan was to send a suicide bomber into where we were, and in doing so, cause as much devastation as possible, and flush everyone out onto the street. Then, when we were out on the street, they would send a car bomb in to clean more tourists up.

HM: You’d lost hearing too?

JM: Most of it – the first blast perforated my ear drums. I was on my own out the front, and that’s when Mick appeared. He had some injuries, but very minor in comparison to what mine were, and he took control and got me out of there.

HM: And he was standing just to your left – but largely unaffected?

JM: It’s like when you see the devastation of bushfire … one tree is fine, and everything else is broadly decimated. Mick and I were like that. Our situation, where one gets badly burnt, one with minimal injuries, one or two lose their lives, some lose limbs, isn’t unusual. But we both made it out – we were both lucky. Mick had minor burns and perforated ear drums, but he was relatively unscathed compared to others. There were a lot around that weren’t as lucky.

HM: It must be the most confronting situation, being surrounded by those who had just been killed.

JM: It is. It’s hard to erase. I saw a bit, too much maybe, but my heart goes out to all of those people that weren’t directly involved but came to support. Whether it be at the site or the hospital, what they came across … it is hard to describe. When you’re really badly injured, and in the madness of it all, and your body is going in and out of shock, it’s a blessing that you don’t take it in as much.

HM: Those that came to assist arrived to human devastation.

JM: People were wheelbarrowing ice into a makeshift morgue out in a passageway. They would lay the bodies on the ice to stop the deterioration in the heat. It was something you can’t imagine ever seeing.

HM: Did you know your life was in danger?

JM: Not initially. I thought once I was out I was safe, but then the extent of my burns and injuries became apparent. I was operated on in the early hours of Sunday morning and very quickly, because there were so many people to operate on. They did an amazing job. This was at the local hospital in Denpasar.

HM: Was it adequate for what was needed?

JM: You can imagine what it would have been like 20 years ago. They were unbelievable with what they did for us all, but no one, and not many hospitals, were prepared for anything like they saw.

HM: What did they need to do with you?

JM: They removed as much of the burnt tissue as they could. I’ve learnt a lot about burns injuries now, and the issue is with infection. Unfortunately, they didn’t have enough dressing to really dress the wounds. They did the best they could with the operation, but then your wounds lay open and are exposed to infection, and that is when the major issues occur.

HM: How many operations did you need in the end?

JM: I’ve never counted the total. I was operated on in Bali on that Sunday morning, and I flew back via Darwin and had more treatment in Darwin. When I got back to The Alfred hospital, I was instantly into surgery. I had 50 per cent burns, so a number of skin grafts, and once again, that’s where I feel pretty lucky. My understanding now is sometimes those grafts don’t take, and you need to go back under for multiple operations. It would have been a fair length of time that I was under, but all those operations were completed in that one hit, and they were all successful. It was a bit of a miracle, really.

HM: The other part that was fortunate was that given you were an adult, you were fully grown. When you’re a kid needing skin grafts, they don’t stretch, and you need to continue to have them.

JM: That’s the hardest thing for kids with burns. I was lucky, all the skin grafts took, and I had no more growing to do. For the kids, the number of operations year on year – because that skin will not stretch with the rate of growth in a child or a teenager – is horrible. I also think a lot about the disfigurement. For an adult, you can live with that, but for a kid – you can’t begin to imagine what that would be like. The bullying they have to go through. I really feel for the kids that sustain burn injuries.

HM: Did you come close to losing your life?

JM: I had a week in an induced coma. I got back to The Alfred hospital on the Monday and was straight in for multiple operations around the skin grafts. Beyond that, within 24 hours, I was really struggling to breathe. That was around the infection. It was taking hold. I remember one night where I couldn’t do it on my own anymore. As bad as it sounds, and as close as I was to losing my life, the induced coma gave me the best chance of beating it. Your body can just shut down, and the medication, the drugs, they just take over. Your body can rest, and it can help you fight it.

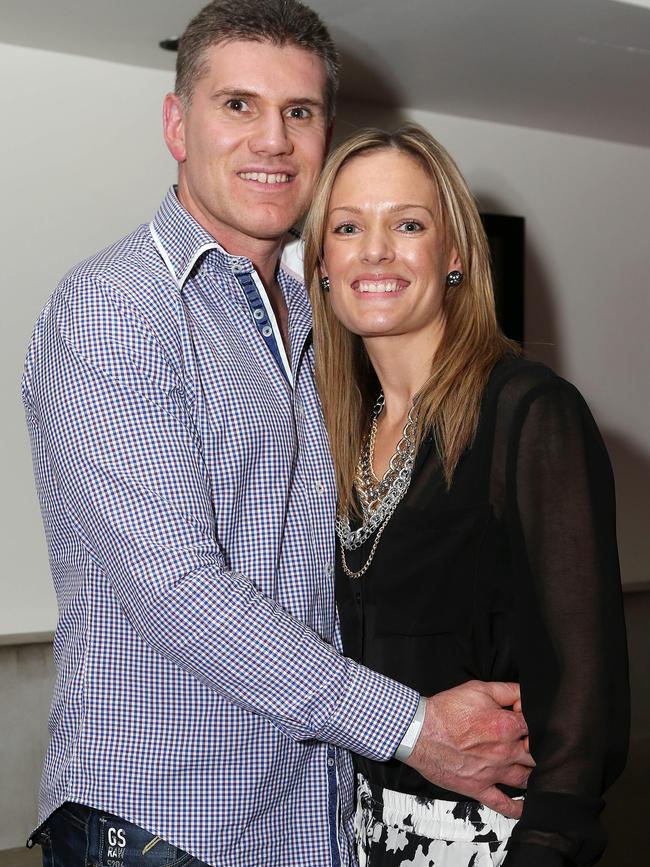

HM: All of this trauma – and struggling for life – is not the ideal prep leading into your wedding?

JM: (laughs) No … it’s not. If Nerissa wanted an opportunity to get out, she had the get-out-of-jail pass!

HM: In your recovery you said, “I’m going to do two things. One, I’m going to get married in 63 days. And then, I’m going to return to football again.”

JM: That’s right. There’s no doubt the wedding gave me a focus, and everything that football had given me in terms of my skill sets – training, the mental application, mental toughness, the disciplines, and the goal setting – was a huge help. I was able to narrow my focus in the short term, and that was all about the wedding.

HM: Your surgeons didn’t agree with you around the timing.

JM: My surgeons, who were amazing, told me I’d have eight to 10 weeks in hospital. That wasn’t going to work for me with the wedding coming up in mid-December. I took that on board, but my mindset was “I can do this, and I will get there”. I had a plan in place with my physio at the hospital; I had everything mapped out. It was tough, but doable. I’d never had injuries like that before, but pre-seasons every year were really tough. I just had to knuckle down and get stuck into what I could control. The only thing I could control was my rehab. I got out in about 3½ weeks.

HM: Not 10!

JM: The Alfred were fantastic, they allowed me to come back as an outpatient each day to continue with my rehab. That gave me the next four weeks to get fit and strong enough to be able to handle that wedding day. I’d lost 12kg, and getting closer to that wedding day, I’d just started to run a little bit again. I was still pretty weak. I didn’t want to just make it there, I wanted to be able to enjoy the day. I was strong in the mind. I thought, “Yes, this has happened, but for me to recover, I need to get back and do everything I was beforehand.” That really helped fast-track that whole process returning to play footy again.

HM: You were long odds to play footy again, weren’t you?

JM: Huge odds, especially at AFL level. It’s hard to put into words, but those disciplines that have been ingrained in you since you were 16 help you believe you can though. You do take it for granted, particularly early on, but they’re wonderful life skills. That determination and focus on a goal and wanting to get back and achieve it was critical.

HM: What was the process?

JM: I returned to training in January – the body had done a great job of healing. The grafts had taken well. I had a really good run right until a month or so before I got back to AFL level. I had a minor calf injury, and that was the only moment where I thought, “Maybe I can’t play again”. I’d had a decent hole blown in my left calf from the shrapnel, and that caused a few problems. I felt like I was so close to getting back into the AFL team, and then the calf happened and I felt I had gone backwards. It made me reflect on my career. We talked about missing out on premierships earlier, and it just got me thinking, maybe this is not meant to be.

HM: You don’t seem to be a negative thinker.

JM: It was one of the rare occasions I was. I thought, “I’ve missed out on playing in premierships, I’m going on holidays and things like this are happening to me. I was so close to returning, and now, I’m injured again.” I thought, “Maybe that’s how it goes for me.” That was my lowest point in that chunk of recovery. Thankfully, Nerissa talked some sense into me, and Anthony Stevens and Glenn Archer had a chat to me the next day. I was close to giving it away then, but I’m glad I listened to those guys.

HM: What did they say?

JM: They just put perspective on it. It’s a calf injury. With what happened, you look back, and you’re probably allowed to have a couple of flat spots. I didn’t have too many. I got some really logical advice, hung in there, and three weeks later, I was back playing AFL. To be honest, that was when I realised that I couldn’t keep going.

HM: Mentally or physically?

JM: A combination. The extent of the burns, understanding that it would take a good two years to heal properly. I was 29 at the time, and I realised there were other things that had become more important in life. Football had been huge, and continues to be so, but when you go through something like that, your family and your life beyond the playing days becomes more important.

HM: The McCartney game was pretty hard to script. It was Hollywood-esque.

JM: It was remarkable how it panned out. It was a really tight game against Richmond, prime time. When I look back, rotations weren’t big in AFL football then, but I spent the whole first quarter on the bench. The second and third quarters, I had limited impact, but then in that last quarter, to be able to kick a goal early, and then very late in the piece I had a hand in the goal that got us across the line to win. I thought Denis Cometti summed it up really well: it was an absolute fairytale ending. You couldn’t have scripted that any better.

HM: No one really knew that it was your last game. There was a handful of players, and the coach.

JM: I spoke with Geoff Walsh, Tim Harrington, Dani Laidley. After the Friday morning team meeting, we had a leadership meeting. We didn’t talk to the rest of the group about it, so it was only those guys that knew. We got the result, and for anyone that’s interviewed on the ground after the game, the spectators never usually hear that. Normally it’s just for the TV audience, but I’d spoken to the club, and because it was our home game, we thought it would be good if the interview could be heard across the PA at Etihad. When we got in after the game, there was a lot of those young guys, and they didn’t have a clue what had just gone on! There was a handful of young guys that didn’t have a clue that I’d actually retired. It was amazing scenes in the rooms afterwards.

HM: It was like a premiership.

JM: It was. We went up to the Victory Room for the after-match, and I’ll never forget that for as long as I live. It was like grand final night – we couldn’t fit everyone in! The band was playing, I was interviewed up on stage, and it was an unbelievable feeling in there. That was the first time I’d realised the enormity of everything. I was so focused on getting back to normality, I hadn’t even given it a thought until that stage about the positive impact it could have on so many others. Through the power of sport, and the sport we love in AFL, you are able to have a positive impact on so many other people.

HM: I remember watching the match in tears, thinking, “This is one of the great unscripted sporting dramas, playing out in real time.”

JM: It’s still hard to believe. It was 18 years ago.

HM: From all of the trauma, drama, and the experience, how in any way has it helped you?

JM: You realise you are very lucky to have a second chance at life. And how precious it is. Like a majority of footballers, before that happened, I was 28 years of age, fit, healthy and felt bulletproof. It sharpens your focus and perspective on life, and life past football.

HM: You must have also at some stage realised what an amazing woman you had by your side in Nerissa?

JM: I had a fair idea beforehand, but she went way above and beyond through that process. In those times in hospital, she was unwavering, day and night by my side, refusing to give up. She was such strong and critical support. Absolutely remarkable. It would have been harder for her. She is there, in the unknown, and you talk about that experience in the coma. There was a period where Nerissa, Mum and Dad were told by the doctors that it wasn’t looking great and it might not work out. Luckily it did.

HM: You mentioned earlier how complicated it is to be a burns victim, but even more so as a child given the nature of the immature minds around them and the bullying. The KIDS Foundation is something you and I both support for good reason. The camps they run make integrating back into the everyday, a little easier.

JM: There’s no doubt about that. I remember my first introduction to Susie O”Neill, who runs the Foundation. It was when I returned to the club in 2003, and that was the start of an 18-year relationship. My wife actually became heavily involved and ended up working there for a period of time. They’ve done some amazing things. When I reference the burns survivor camps for the kids, it’s about helping with the healing process mentally and physically, by bringing a group together. You come from being in a minority at school to feeling normal again. They can come away on a camp and share their stories with others who are going through similar challenges. It’s so empowering. I really struggled with the first day at the camp as everyone was arriving. I’d been through a bit, but the part that I struggled with was I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing when people were arriving, hearing some of their stories. Some of the incidents weren’t accidents. You wouldn’t wish a burns injury upon your worst enemy.

HM: The camps give them back their confidence.

JM: The trauma of the disfigurement, the ongoing operations over a number of years until they get to that adult stage when they’ve stopped growing – that acceptance in the community is enormous. In my situation, people were very familiar with who I was because of AFL. It’s not like people were looking at me dressed in garments, wondering what had happened. They knew. It would be so much harder with people looking at you, wondering what happened. These camps are a great opportunity for people to come together over three or four days, with great support around them, psychologists, and activities where for that period of time you are accepted and you’re normal again. It breaks your heart for kids to have to go through something like that.

HM: Well said. I interviewed Mike Sheahan a few years ago and he listed his five most emotional moments in football. The McCartney Game was No.1.

JM: He came and spent a day with Nerissa and I in at The Alfred during my rehab process. He is a great man. Thanks, Hame.

You can support the Kids Foundation at putyourhandup.org.au

More Coverage

Originally published as Hamish McLachlan: Footy hero Jason McCartney on why he’s a lucky man