The rise, fall and future of Colleen Gwynne: Children’s Commissioner considers next moves after not-guilty verdict

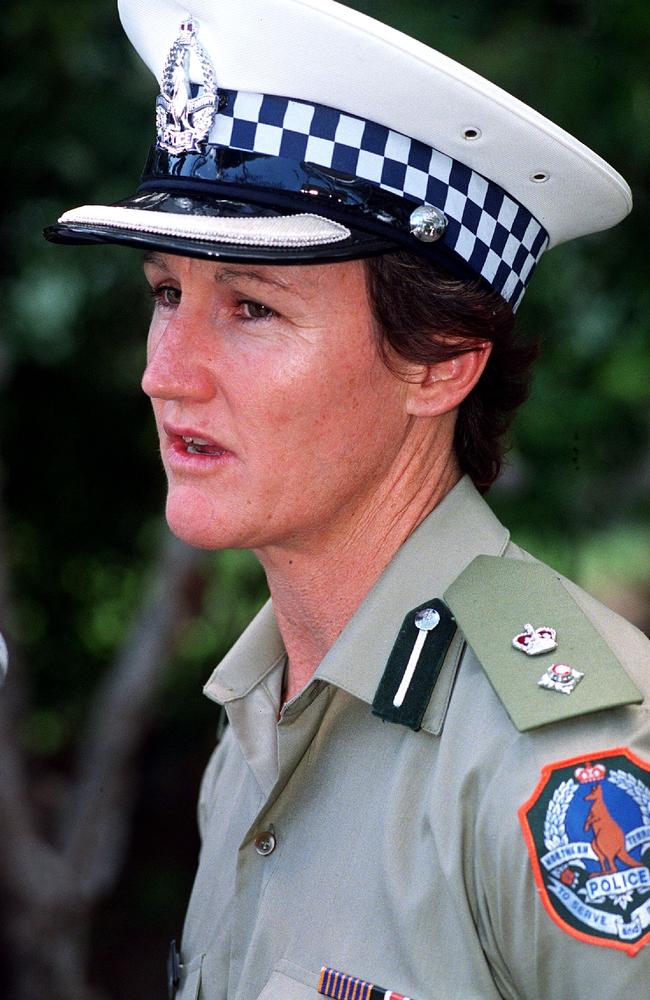

From a childhood of violence to a career in the police force and ultimately being appointed Children’s Commissioner, Colleen Gwynne climbed the ranks of the Territory. But her rise has not been without political controversy.

Politics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Politics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Four days was all it took for a three-year investigation into the NT Children’s Commissioner to blow up, leaving behind her 26-year police legacy and eight-year stint as the children’s safety watchdog in smoke.

On Tuesday, Colleen Gwynne was found not guilty of abuse of office, bringing the six-week Supreme Court trial to an abrupt end after four days.

After a legal decision by Judge John Burns, prosecutors dropped their case and urged the jury to deliver a not guilty finding.

With her name legally cleared, Ms Gwynne stood on the steps of the Supreme Court to ask for time to consider her future in the Territory.

The former NT Police officer turned children’s welfare ombudsman was known across the Territory for her unflinching criticism of the systems to protect young Territorians, becoming known as a ‘welfare warrior’.

The 56-year-old has led many lives in the Territory, through her 26 years with the NT Police, as the lead investigator in the Peter Falconio case, a major crimes chief and the subject of political controversy.

Childhood

Ms Gwynne carved out a career to protect children and victims from homes marred by abuse, violence and volatility — childhoods very similar to her own.

In 2008, she publicly shared stories of her youth, growing up as one of eight siblings in Port Victoria on South Australia‘s Yorke Peninsula.

“Our father was a builder and a fisherman. A really bad fisherman. As a family, we struggled,” Ms Gwynne said.

“My father used to beat up on my mother. He was a terrible alcoholic, an extremely violent, very intimidating man.

“I'll never forget one night when I was about 10 and my father was taunting my mother and going off.

“(My brother) Phillip was only 17 or 18 at the time. My father was a really big man – he weighed 100-plus kilos – and Phillip threw him through a glass door. I remember thinking, ‘Thank God Phillip is here to protect us’.”

Ms Gwynne said she left home at 18 with no plan for what her future would hold, later saying: “I didn't really know what I wanted to do in life. I couldn’t stay home. I just couldn’t be there”.

In 1985, the then-teenager helped her mother escape the violent home by organising a rented house in Adelaide, helping her mother pack and move without warning, then living there for 18 months to protect her.

“My mother is the most robust, amazing woman, but I think the strength in her had been sort of belted out of her,” she said.

“Every time I speak to her it reminds me of what my father put her through.

“I haven‘t spoken to my father for 20-something years. I’ve tried, but I couldn’t ever forgive him for what he’s done,” she said in 2008.

Ten years later in a 2018 interview with The Australian, Ms Gwynne said she did not go to her father’s funeral.

“As other people who have grown up in a violent household will tell you, you’re always in almost a state of alertness,” she told The Australian.

“And I think that’s what I went through. I think it helps me to understand how others feel.”

POLICE CAREER

Ms Gwynne joined NT Police in 1988 at 22 years old, entering yet another world of violence, alcohol and abuse — but this time in a position of power.

“When I joined in the late 1980s there was only a handful of us who were operational at the time — now you could walk into some areas and see more women than men,” Ms Gwynne said in 2004.

After 14 years on the frontline, Ms Gwynne rose to the rank of acting superintendent of the Alice Springs region but the promotion in 2002 came with what was seen at the time as a ‘poison chalice’.

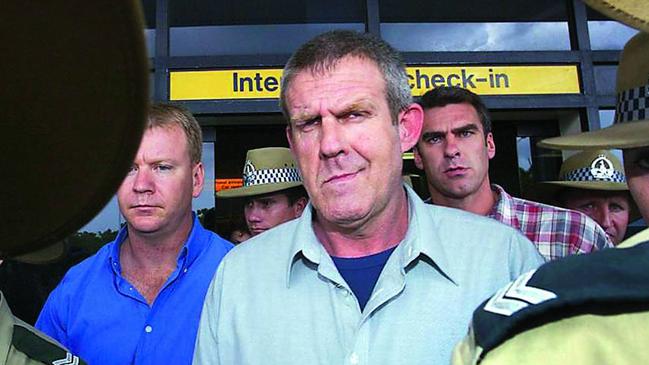

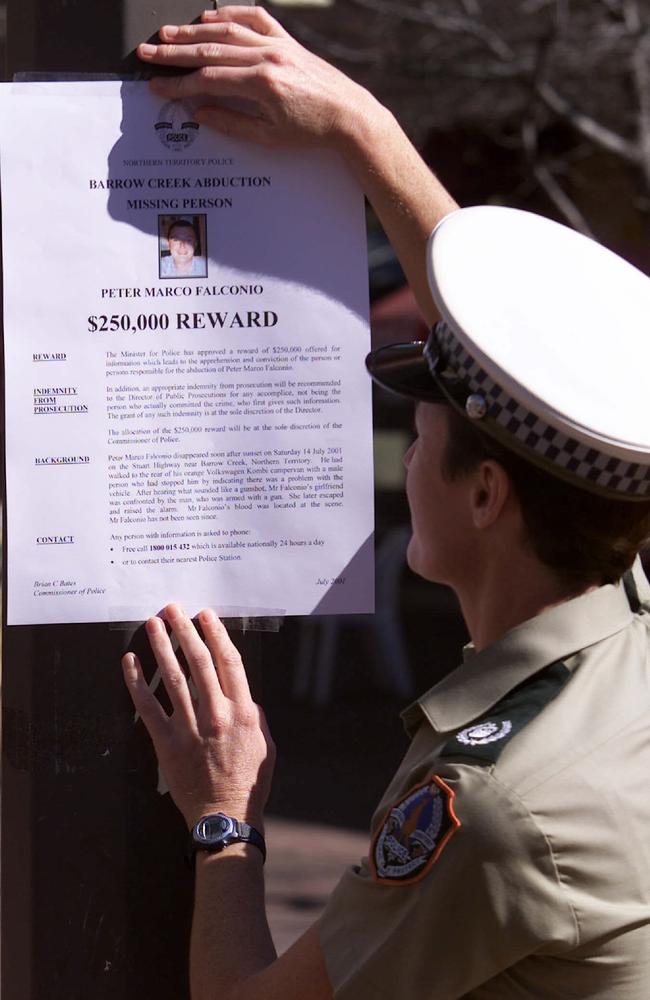

Only six months earlier, a distressed Joanne Lees flagged down a truck driver on a darkened stretch of the Stuart Hwy after hiding in bushland for five hours after being attacked by a gunman.

The national spotlight narrowed on that vast stretch of desert in search of Ms Lees’ boyfriend turned missing person, British tourist Peter Falconio.

When Ms Gwynne arrived to the case the police investigation had turned up no body and no prime suspect.

Ms Gwynne would lead the national search for Bradley John Murdoch, eventually tracking down the murderer to South Australia’s Yatala prison.

Despite being convicted for Mr Falconio’s murder, Murdoch continuously maintained his innocence — particularly with the greatest remaining mystery being the failure to ever find the missing backpacker’s body.

As the chief investigator, Ms Gwynne told the media that finding Mr Falconio’s body would “be like finding a needle in a haystack”.

She has said there was no hope of Murdoch ever telling police or Mr Falconio’s family where the body was.

“For the victims, to find the body is probably as important as a conviction,” Ms Gwynne said reflecting back 15 years on.

“He’ll always maintain his innocence; he’ll take that to his grave,” she said in 2016.

“He’s an extremely arrogant man, so he still feels like the system’s done him wrong. He’s not about to then provide us with information to try to locate Peter.”

Even after leaving the police force, Ms Gwynne would be called on to debunk fresh dodgy tip-offs, rumours, innuendos and lies circulating about the two-decade-old mystery from the heart of the desert.

After the Falconio case, Ms Gwynne was promoted to the upper ranks of the force moving to Major Crime where she would deal with bikies, drug syndicates, murderers, rapists and mayhem.

As a police officer, Ms Gwynne would investigate high-profile incidents involving young offenders.

“One of the problems we as law enforcers are faced with each day in the Territory is the number of children who roam the streets 24 hours a day, committing crimes,” Ms Gwynne said following a 2011 fatal fire linked to a 12-year-old and a group of kids.

“It’s a concern for the community, not just police.”

NT CHILD ABUSE TASKFORCE

Ms Gwynne established the NT Child Abuse Taskforce where she would investigate violence, abuse and neglect of Territory kids.

In 2004, a police investigation allegedly uncovered more than 10,000 images of child sexual abuse in raids of 14 homes across the Territory, including in Darwin, Alice Springs and Tennant Creek.

“(They) are the most extreme that we have ever seen here in the Territory,” then-Organised and Major Crime Squad acting commander Ms Gwynne said.

When ABC’s Lateline published claims in 2006 that petrol was being exchanged for sex with children in Mutitjulu, it was Ms Gwynne who investigated the findings.

After police interviewed almost 300 people in Mutitjulu, Ms Gwynne told the media in July that year the report may have been overstated.

“There’s still no direct evidence that identifies anyone who has sexually abused any children in Central Australia,” Ms Gwynne said at the time.

“We have found some evidence of petrol being provided to children.

“We haven’t found any evidence of petrol being provided for sexual favours.”

Despite police rebuking the ABC claims, these and other stories of child abuse in the Territory were used to justify the 2007 Intervention, with former prime minister John Howard famously declaring the situation a “national emergency’’.

In 2007, then-police commander Gwynne investigated after a 12-year-old girl in foster care died in a Palmerston home from chest, blood and bone infections related to a leg injury three weeks earlier.

The investigation led to a coronial inquiry and the Territory government announced an audit of all high-risk children in foster care.

In 2004, the NT News reported that girls, mostly from Yirrkala, near Nhulunbuy, were having sex with mine workers in exchange for cannabis and money.

Four years after the reports, Ms Gwynne headed a special taskforce in Nhulunbuy, which knocked back claims of the child sex trade.

“Unfortunately some appear to have arisen from rumour which has been unable to be substantiated and other reports of child abuse (which have been made publicly) actually involve consenting adults,” she said in 2008 as acting assistant police pommissioner.

Ms Gwynne was forced to strongly defend claims police had done nothing about the allegations that had been circulating for years.

She would go on to run Nt Police’s internal affairs division, the Ethical and Professional Standards Command.

But Ms Gwynne left the police in 2013 after 26 years with the force.

Her police boss, commissioner John McRoberts denied in 2013 that one of his most high-profile officers had quit after an argument over an internal investigation.

As head of the Ethical and Professional Standards command, Colleen Gwynne acted as the assistant commissioner in 2011 but the permanent role was instead given to AFP officer Reece Kershaw, who later went on to become the AFP commissioner.

It was suspected at the time, Ms Gwynne had ambitions for the second-in-command job but the then-police commissioner McRoberts preferred the interstate option.

CHILDREN’S COMMISSIONER

In 2015, Ms Gwynne was appointed Children’s Commissioner by then-health minister John Elferink.

Her appointment was not without controversy – ironically the same scandal that would plague her office for the past three years.

Mr Elferink, who once worked in the police force with Ms Gwynne, did not advertise the job and faced accusations of providing ‘jobs for mates’.

Mr Elferink maintained Ms Gwynne was not a mate appointment but rather the best person for the job.

“I have seen the quality of her work in the police force and drafting youth justice policy. She is someone I have high regard for,” he said.

Asked why the government did not go through a public advertising process, Mr Elferink said: “The Territory government is unashamedly in favour of hiring Territorians.”

Over her eight years with the Office of the Children’s Commissioner, Ms Gwynne became known for her blunt and unsparing attacks of the child protection system – lashing criticism at the feet of Corrections and Territory Families departments.

In her first formal report as Children‘s Commissioner, Ms Gwynne said the Territory’s child protection system was in crisis and a “bold” policy overhaul was needed to deal with the increasing numbers of children at risk.

“I think we have dropped the ball in how we deal with things at the earliest opportunity,” she said in November 2015.

As Children’s Commissioner she would become a vocal critic of ‘tough on crime’ and ‘bad youth’ narrative around Territory children.

“People just jump on the bandwagon that all kids are bad, they need to be locked up and the community needs to be safe from them. The reality is so far from that,” she said in 2017.

“I am yet to meet a young person who wants to grow up to be a criminal.”

Ms Gwynne consistently highlighted that Territory Families were “too often overwhelmed” by the volume and complexity of child protection matters, called to raise the age of criminal responsibility and improve rehabilitative services for kids caught in the justice system.

Ms Gwynne said Territory Families and police had a “silo” mentality in which they failed to share details critical to the child’s welfare.

She also backed a call to toughen penalties for domestic abusers who bash their partners while their children watch on, calling them the “silent victims” of family violence.

Eleven months before damning footage of children being tear-gassed in solitary confinement aired on national television in 2016, the NT government signed off on Ms Gwynne’s report that revealed the extent of this abuse.

The investigation, carried out by Commissioner Colleen Gwynne, stated on at least 13 occasions “handicam footage” existed of the night tear gas was pumped towards the cells of six teenagers in 2014.

It also made references to the controversial use of “spit hoods” on the children.

Despite the 60-page report, which not only revealed the existence of the footage but a litany of failings, fabrications and breaches of the NT Youth Justice Act, politicians claimed they were in the dark as to what was going on within Territory youth justice centres.

The royal commission was announced – again despite reports from two consecutive NT children’s commissioners detailing the abuse, and three reports into youth justice have been completed since 2011, delivering almost 50 recommendations.

When the 227 recommendations were released in 2017, then chief minister Michael Gunner said the findings would “live as a stain on the Northern Territory reputation”.

“For this I am sorry. But more than this I’m sorry for the stories that live in the children we failed,” he said.

Ms Gwynne said: “There are two things that will determine the success or otherwise of this. Number one isn’t the money; it’s the leadership that the NT government show in this space.”

While the NT government accepted the “intent” of all 227 of the royal commission recommendations, it stopped short of giving 91 of those its full support.

It gave only “in-principle” to 91 recommendations, including raising the age of criminal responsibility, granting the OCC ‘unfettered’ access to youth detention centres, and setting up a body to address rates of child sexual abuse.

The government was given a three-month deadline to come up with a plan to shut Don Dale by the royal commission into youth justice.

At the time, Ms Gwynne said while keeping kids in Don Dale until 2020 wasn’t “ideal”, it was unavoidable.

As of 2023, the new Don Dale centre has yet to open.

Under the national spotlight of the Don Dale findings, and with numerous high-profile child abuse investigations underway, Ms Gwynne told The Australian she had “lost the balance” in her life.

“It’s a busy life, and in all honesty I’d lost the balance and I got to the stage where everything became a task,” she said in 2018.

“I think these jobs have a lifespan and I think for your own wellbeing it‘s not something you can do forever.”

It was around this time that prosecutors alleged Ms Gwynne made a “captain’s call” to appoint her friend and ex-police buddy Laura Dewson as her second-in-command, and was secretly recorded making racist comments about Ms Dewson’s rival for the job, Nicole Hucks.

One of the 2017 royal commission recommendations was the appointment of a Aboriginal Co-Commissioner, which Ms Gwynne backed.

“You need to be reflective of your target group,” Ms Gwynne said.

FOOTBALL

Ms Gwynne was among three women who were the first to be appointed to the AFLNT board in late February 2016, shattering the ‘boy’s club’ reputation.

Ms Gwynne was a five-time premiership coach for the Waratah women’s football team.

In 2016, the NTFL Women’s Best and Fairest Award was renamed to the Gwynne Medal, in recognition of her role in developing women’s football in the Northern Territory.

But on Friday afternoon, the AFLNT board reverted the name back to Women’s Premier League Best and Fairest Medal.

She was also an assistant coach for the Adelaide Crows women’s team.

A former AFLNT director, Ms Gwynne mentored the Arnhem Crows to a title in the 2020 Big Rivers Football League competition.

THE CHARGES

On Thursday, July 16 2020, police media released a statement saying a 54-year-old female had been issued with a notice to appear in court on Thursday, August 27 on a charge of abuse of office.

“The charge has been laid after an investigation by the Special References Unit,” it said.

“As the matter is now before the court no further comment will be made.”

A day later, this publication reported Ms Gwynne was the female who had been charged, reporting the charges were related to the hiring of a staff member.

At the time, a spokesman for Ms Gwynne said she would be vigorously defending the charge.

Following the three-line police announcement, police did not respond to questions from media including questions after Ms Gwynne said she was not offered an interview.

NOT GUILTY

Last Tuesday, Ms Gwynne was cleared of a charge of abuse of public office in a sensational move on day four of her Supreme Court trial.

Prosecutor Georgia Wright told Justice John Burns she had been advised by the NT Director of Public Prosecutions to drop the case against Ms Gwynne.

“It is our position that the Crown will produce no further evidence and there is no objection from the Crown to the verdict of not guilty being entered,” Ms Wright said.

Justice Burns told the jury that following his decisions on certain questions of law, the Crown had withdrawn its case.

“There has been a development in the trial, and I do not know if it will come as a pleasant or unpleasant surprise to you,” Justice Burns said.

THE FUTURE

Outside court on Tuesday, Ms Gwynne said she welcomed being found not guilty and needed time to consider her “future” as the children’s safety watchdog.

Ms Gwynne said she had been humiliated and victimised by the three-year investigation that she claimed targeted her.

“At no stage have I ever been interviewed by investigators,” she said.

“Key witnesses, who would have demonstrated my innocence were never spoken to.

“The humiliation and victimisation to which I‘ve been subjected, merely for doing my job is something that I’ve had to endure in silence.

“I watched with increasing despair as the case took a life of its own.”

Ms Gwynne also apologised for racist comments she made while being secretly recorded by police.

“I acknowledged those words were extremely offensive. I am mortified that I ever expressed my anger and frustration in that way,” she said.

“Those people who know me, know this is just not who I am.”