Colleen Gwynne, the Northern Territory Children’s Commissioner, rises to the challenge

She caught Peter Falconio’s killer and blew the lid on Don Dale, but what Colleen Gwynne found in Tennant Creek shocked a nation.

At 8.30 on a Friday morning in Darwin, Colleen Gwynne has been at her desk for two hours and the day is already looking complicated. Here in the office of the Northern Territory Children’s Commissioner, phones are buzzing about the latest news in the shocking rape of a two-year-old indigenous girl in Tennant Creek – police arrested the wrong man, locking him up for three months before charging another suspect. Meanwhile, a five-year-old from the same community is in hospital in Alice Springs after another reported sexual assault, which the police are saying is serious but welfare officials insist is relatively minor, leaving Gwynne floundering to find out what really happened.

It’s 29 days since she handed the Territory government a damning 102-page report into the case of the two-year-old, urging police and welfare workers to co-operate more effectively and revealing that the girl’s family had racked up 52 child protection notifications over 16 years. So there’s a weary feeling of déjà vu as she schedules meetings to clarify what exactly is going on in Tennant Creek, almost 1000km to the south.

“I have sympathy for those frontline officers – I was one of them for many years,” says Gwynne, 52, referring to her 26-year career as a Northern Territory cop. But Tennant Creek is a small place, she points out; fewer than 3000 people are serviced by scores of police, health and child protection workers. It’s one of the most heavily monitored communities in the nation, yet its vital statistics on violence, child sexual abuse and health are all heading in the wrong direction.

“It’s not a lack of resources, it’s the application,” she continues, as Darwin Harbour glitters in the window behind her. “What are we doing today, with the number of vulnerable kids we’ve got in our community? I just don’t think we’ve got a very good handle on that. We don’t seem to have enough people who can lead the response with passion and optimism. We seem to be burnt out. A lot of what would shock people who come into the Territory has become very much normalised.”

Welcome to another day in the slow-motion catastrophe that is child welfare in the Top End. When Gwynne accepted the Children’s Commissioner’s job three years ago she expected it to be difficult, and it hasn’t disappointed. Much of her first year was spent investigating the infamous Don Dale juvenile detention centre outside Darwin, where the use of tear gas, restraints and spit-hoods against teenage inmates sparked global outrage and a damning royal commission report. The Tennant Creek sexual assaults, meanwhile, have created the biggest crisis in the Territory’s welfare system since the Howard government ordered the National Emergency Response 11 years ago.

Gwynne has been blunt and unsparing in her criticism of these debacles, angering some of her fellow bureaucrats in the departments of Corrections and Territory Families. The NT Children’s Commissioner has broad power to investigate and report on failures in the child welfare system; that can be tricky in a city of only 106,000 people, where the people you’re sharing a lift with might be the same ones you just publicly named as incompetent. “The Northern Territory is such a small community – everyone’s accessible, so I could be out at my kids’ soccer game and be standing there with my minister, the media and people involved with service delivery. It can be really difficult, because your Act stipulates you have certain functions. I’ve got to make sure I represent the interests of vulnerable children, and sometimes that’s not palatable to people who are actually colleagues or friends of yours.”

Gwynne’s week had started with a flight to Alice Springs, where she took part in an indigenous reconciliation event and a meeting of the Australian Football League’s NT board. Away from her child protection work, she’s better known to Top End sports writers as an “AFL legend” with 11 premierships to her name as a player and coach, including assistant coach of the Adelaide Crows women’s footy team. She got her start in the game as a 10-year-old masquerading as a boy in rural South Australia, playing midfield due to her diminutive stature, and 42 years later she still walks with the rapid bob-and-weave gait of an AFL tagger. She kept playing until she was 49 and still boasts an athlete’s lean muscularity, although she gave up coaching recently to spend more time with her two young children.

Gwynne is a passionate believer in sport as a great leveller for divided communities and a pathway out of trouble for at-risk kids. But the day she’d arrived in Alice Springs, the front page of the Centralian Advocate featured the words YOUTH CRIME in giant typeface over a photo of a shattered window, and the taxi driver who took her into town complained bitterly about marauding kids vandalising shops and cars. At the reconciliation event she’d met Martin Luther King III, son of the famed civil rights leader, who was back in Australia for the first time in 20 years and visibly chagrined by the deterioration of indigenous town camps. Gwynne was the only white speaker at the event, carefully advising the Arrernte elders that everyone had a role to play in curbing rising rates of indigenous infant mortality and school truancy.

She’s still mulling over the trip a couple of days later when we meet in Darwin. As a cop she spent nearly four years in Alice Springs and remembers the early 2000s as a more optimistic time when Labor governments were trying to divert youths away from jail and into “restorative justice” programs, in which offenders meet their victims. Those programs work, she insists. But the Country Liberal governments of 2012-16 reverted to lock-’em-up rhetoric, led by a chief minister, Adam Giles, who labelled young offenders “mongrels” and threatened to revoke their bail rights. Police proceedings leapt by 57 per cent over those years but the promised 10 per cent drop in crime never happened and the murder rate is still five times the national average.

“The media here are quite powerful in painting kids in a poor light,” Gwynne says as she drives to an event at an outer Darwin high school, dressed in sleeveless shirt, capri pants and sandals. “What we’re doing at the moment is panicking… we’ve been caught up in all this rhetoric about keeping the community safe by locking kids up, not understanding that every time we do that we’re actually making the situation worse.” Governments keep announcing inquiries, she says, when the real solution is getting police and welfare workers to work more closely with at-risk families.

“It’s like the AFL – there’s too much hand-passing backwards instead of grabbing the ball and getting it on the boot,” says Gwynne, who has a Territorian’s knack for slinging dry one-liners from the corner of her mouth. “Look, I do use a few footy analogies,” she adds, “and that’s one of them.”

Speaking out in defence of juvenile delinquents can get you pigeonholed as a bleeding-heart lefty in the charged politics of the Top End, which makes one wonder why the Giles government hired Gwynne in the first place. The man who appointed her – former attorney-general and corrections minister John Elferink – replies simply that she is “the epitome of integrity”. A former cop himself, Elferink first met Gwynne when she was a junior constable, and he knew her history well: as an investigator she cracked the Peter Falconio murder case; later she ran internal affairs and a child abuse taskforce, and was acting assistant commissioner at Darwin police HQ. “I knew she would bring a counterpoint to government and do that quite fearlessly,” says Elferink, “because she’s a courageous human being.” It’s a phrase others use about Gwynne, for different reasons.

When Peter Gwynne describes his sister Colleen as the bravest person he’s ever known, he’s thinking about the way she stared down Falconio’s killer, Bradley John Murdoch, a hulking man 30cm taller than her. He’s thinking of the year she spent in Papua New Guinea as part of an Australian aid program, travelling with an armed escort to meet ultra-violent raskol gangs. More than anything, though, he is thinking about the day in 1985 when his teenage sister helped their mother escape the violent home in which they had all been trapped for years.

The youngest of eight kids, Peter has childhood memories of a loving mother, a rambunctious pack of siblings and a towering, intimidating father whose booze-fuelled rages cast a terrifying shadow. Bernie Gwynne was an angry man who worked briefly as a fisherman in the small coastal town of Port Victoria, two and half hours’ drive west of Adelaide, before moving his family 300km east to Waikerie on the Murray River, where he ran a roadhouse. “The cycle of violence was something you could see,” Peter recalls of his father, who died two years ago. “He’d be good for a while but it would slowly build and then he would crack, and you knew you were in for it. I have memories of us hiding out in the orange trees, shitting ourselves, while the old man was wrecking the house.”

Colleen Gwynne wonders today whether her father suffered an undiagnosed mental illness; she credits her mother with somehow fostering a spirit of play and fun while bearing the brunt of her husband’s rage. What went on in the house was rarely spoken about outside it, and even today Gwynne talks guardedly in deference to her mother, who is in her late 80s. “As other people who have grown up in a violent household will tell you, you’re always in almost a state of alertness,” she says. “And I think that’s what I went through. I think it helps me to understand how others feel.”

It’s perhaps telling that three of the Gwynne kids – Colleen, Peter and their sister Julie – would go on to become cops. Like most of her siblings, Colleen moved out of home as soon as she was able, initially hoping to pursue an athletics career. As a girl she had been so sports-mad that she snuck into the all-male Waikerie Magpies Under-12s footy team, prompting outrage among some parents. But there was no career path for girls in AFL – Gwynne was banned at 14 and wouldn’t resume playing for nearly 20 years – and a ligament injury when she was 21 cruelled her ambitions as a netballer.

She was 19 when she resolved to rescue her mother from their father by organising a rented house in Adelaide, helping her mother pack and move without warning, then living there for 18 months to protect her. The fear of retribution was real, Peter recalls. “Colleen was scared he would find them, and he definitely tried to look for them initially. This is in the days before mobile phones. She’s only small, he could have done anything, but he was a typical abusive alcoholic – he was gutless, really.” Bernie Gwynne would live for another 30 years without ever speaking to his youngest daughter, who did not go to his funeral.

Joining the NT Police at 22, she discovered she loved the nitty-gritty of community policing, despite the intractable problems of alcohol and domestic abuse that consumed much of her day. She was a gay woman in a workplace not renowned for its enlightened gender politics, but has no memory of running into obstacles. “I didn’t experience it,” she says flatly. “I always thought I was chosen on merit and I never found there were any issues with my sexuality or my gender.”

By 2002 she was acting superintendent of theAlice Springs region when police commissioner Paul White called to deliver some good news with a sting in its tail: she was being promoted to full superintendent, and that meant she’d be taking over the most blighted, controversial and closely monitored police investigation in the nation, the Peter Falconio murder case.

It had been eight months since Falconio had disappeared while driving a Kombi van north of Alice Springs with his girlfriend Joanne Lees, and the story Lees told had created a media sensation: two innocent Brits on an outback holiday, flagged down at night on a lonely desert highway by a Toyota LandCruiser driven by a hulking outback psycho, who shot Falconio and trussed up Lees with cable ties, only for her to escape into the wilderness. A police investigation had turned up no body and no prime suspect, and British reporters were openly suggesting Lees was complicit in her boyfriend’s disappearance. It was the biggest story in the Territory since the disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain at Uluru in 1980.

Gwynne’s former colleague, retired superintendent Megan Rowe, recalls that the case was a “poisoned chalice” thanks to the incessant publicity and the early blunders made by police. DNA samples had been contaminated, the desert where Lees escaped had not been properly searched and mountains of material had been collected on 2500 persons of interest without any coherent filing system. Gwynne remembers arriving at the taskforce office to find case notes piled by the hundreds on desks. “There was no sophistication around the collection and analysis of the information – none whatsoever,” she recalls. “There was no robust crime plan. I was definitely daunted by the task, but somebody had to get across the details.”

Gwynne spent two weeks reading through the files and drove out to the desert where Lees said she had hidden for five terrifying hours before flagging down a passing truck. Flying out to England, she won the confidence of Lees, who was aggrieved at the way police and the media had treated her more as a suspect than a victim. The case had become a full-blown circus, with psychics suggesting the location of Falconio’s body and multiple eyewitnesses swearing they’d spotted the missing Englishman alive in more than 30 different locations. “In defence of the guys in the taskforce, they were spending more time answering questions from within than doing their job,” recalls Gwynne. “The fact that they kept their sanity was remarkable, because they were working such long hours, and they were completely dedicated.”

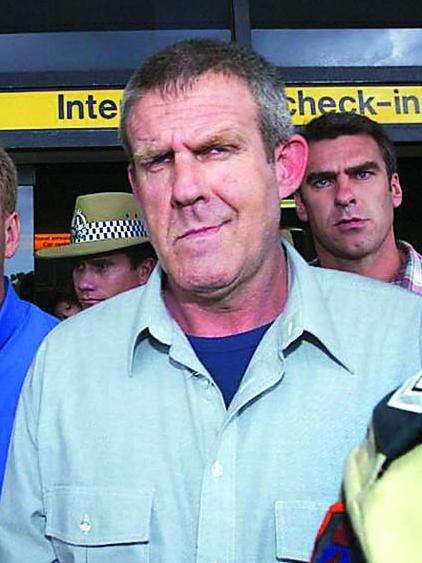

Rowe recalls that Gwynne began fielding the calls herself and shielding her team from the madness. Two months later they got a red-hot tip: a Broome drug dealer called James Hepi had information suggesting that Falconio’s murderer was Bradley John Murdoch, an amphetamine addict who regularly drove drug shipments on a 3600km desert run from outer Adelaide to north-west Australia. Unable to find Murdoch, Gwynne’s team issued a national alert for him; three months later he was arrested in South Australia, charged with raping a 12-year-girl and her mother. In 2002, Gwynne flew to Yatala prison in South Australia to confront him, an encounter that would leave her more deeply shaken than she anticipated.

Murdoch is nearly two metres tall, with a head like a block of concrete and a brooding presence; Gwynne is a mere 170cm and was already trembling with anxiety when Murdoch walked into the prison meeting room. She saw that the mugshots didn’t lie: he was the very image of the father she had once feared. It was a brief encounter in which she recalls him looming over her, “yelling and spitting” as he denied any involvement in Falconio’s disappearance, just as he would deny and be acquitted of the South Australian rapes.

It was another three years before Murdoch was finally convicted of the Falconio murder, a victory for police that’s often portrayed as the result of more luck than skill. Journalist Paul Toohey’s riveting account of the case, The Killer Within, depicts Gwynne’s team as a bunch of blunderers whose sloppiness helped Murdoch remain at large for more than a year. That’s a judgment Gwynne strongly refutes. Whatever mistakes were made early on, she says, they built a successful case without a body using compelling circumstantial evidence: eyewitness testimony, DNA linking Murdoch to the cable ties and the blood on Lees’ T-shirt, and a hair tie of Lees’ that Rowe found among Murdoch’s possessions.

Promoted to the upper ranks after the Falconio case, Gwynne initiated the NT Child Abuse Taskforce, filled in as assistant commissioner for 18 months and ran internal affairs. But she never enjoyed a close relationship with then police commissioner John McRoberts, for reasons that can be guessed at: McRoberts is facing jail for attempting to pervert the course of justice after trying to stymie a fraud investigation into a travel agent with whom he was sexually involved. Gwynne left the police in 2014, not long before that scandal broke. Asked whether she ever applied for the commissioner’s job, she replies drily: “In hindsight I should have given it a crack… I might have saved some embarrassment for all involved.”

Gwynne learnt early how thankless the job of Children’s Commissioner can be: when she arrived at her new office in March 2015, her first task was completing a half-finished inquiry into Don Dale juvenile detention centre, the scene of an alleged riot by inmates the previous year. The report she sent to the Giles government five months later was a scathing indictment of the Corrections department, detailing the potentially inhumane use of “spit hoods” and restraints on children, along with videotaped evidence of guards threatening to “pulverise” the inmates. “It wasn’t taken seriously,” she recalls. “The recommendations weren’t taken up, and it was only when the media decided to take up the issue from the kids’ perspective that it got a reaction.” Eleven months after Gwynne filed her report, ABC TV’s Four Corners aired video and photo images of the appalling conditions she had detailed. In response, Giles professed himself “shocked and disgusted”, calling for a royal commission and sacking John Elferink as minister for corrections.

Today Gwynne views the whole episode, including the $54 million royal commission that was jointly funded by the NT and federal governments, as textbook knee-jerk politics. “Did we need a royal commission?” she asks rhetorically. “We all sat back while there was this blame game about who was responsible, and to satisfy both governments’ sense of ‘We’re shocked! We’re going to do something really big!’… I had provided the government with a report; they had the images, they had the video. I had done press interviews, and then when I worked with the government to implement the recommendations they were almost hostile. It was only Four Corners telling the story that created a reaction – and contrary to what people like John Elferink say, they told an accurate story.”

Gwynne clearly gets no joy from voicing such criticisms. Elferink was a minister she personally liked and respected for his reforms to the adult prison system; the head of Corrections was her former police colleague, Mark Payne. The danger of her role in such a crisis-ridden environment is that you alienate the very bureaucrats you’re trying to win over to your arguments. Her predecessor, Howard Bath, spent six and a half years in the job and finished with an irretrievably hostile relationship with his minister and prison officials.

The failure of the Giles government’s law-and-order crackdown has left a void that’s now filled with sharply conflicting arguments about how to arrest the Territory’s alarming statistics on alcohol abuse, domestic violence and child sexual assault. Some indigenous leaders warn of new Stolen Generations as they watch increasing numbers of indigenous children taken into state care; others point to the Tennant Creek incident as evidence that child protection workers are too reluctant to intervene in Aboriginal families. The two-year-old who was raped in Tennant Creek tested positive for a sexually transmitted disease and was so badly injured she required surgery and blood transfusions. Gwynne’s investigation revealed the girl’s family had more than 150 recorded interactions with police and was the subject of 52 child protection notifications covering “all possible harm types”. Her report concluded Territory Families had comprehensively failed to assess the family and intervene appropriately, resulting in a tragedy that was foreseeable.

“The Tennant Creek report is probably the most difficult report I’ve had to write,” she says. “When my finding is that the harm to this two-year-old was anticipated, that’s really tough. To overcome that, to make sure we don’t have other children in those circumstances, the response has got to be urgent and collegiate and collaborative across government. I keep saying we can’t expect one department to solve all the problems across the NT. The biggest challenge we face at the moment is getting all departments to work together.”

Gwynne still believes that indigenous children who are taken into state care should ideally be placed with relatives or an indigenous family, unless that cannot be done safely. Her report included a raft of suggested reforms for police and welfare workers, one of which was to “adopt a consistent definition of cumulative harm”. In response, Territory Families was initially hostile and insisted that its workers could not have foreseen the assault of the two year-old. But the debacle over the jailing of the wrong suspect, which seems certain to cost the NT Government an expensive compensation payment, confirmed the failings she had highlighted. Police have now charged a second man with rape, and last week Territory Families removed 15 children in Tennant Creek from their families, admitting it had revised its procedures since Gwynne’s report was released.

For Gwynne, the stress and workload has not been without personal consequences. Eight years ago she and her then partner had a son by IVF, followed by a daughter two years later. But that relationship ended not long after she took on the Children’s Commissioner job, and earlier this year, when her mother was hospitalised, Gwynne realised that the work/family juggle was getting on top of her. “It’s difficult,” she admits. “It’s a busy life, and in all honesty I’d lost the balance and I got to the stage where everything became a task.” But, she adds drily, “the fact that I’m now coaching an under-7s soccer team is a tribute to the fact that I’ve made some significant life choices”.

Asked when her contract comes up for renewal, Gwynne replies “hopefully soon”, a throwaway quip that suggests she’ll think hard about signing on for a second five-year term. “Dealing with these issues can be so emotive, it can be so hard to keep yourself separate from them,” she says. “I think these jobs have a lifespan and I think for your own wellbeing it’s not something you can do forever.”

If there’s a next step for Gwynne, it seems likely to involve sport. With undisguised pride she mentions that the AFL now has a best-and-fairest medal named after her in the Territory. Many of the young women she has coached and mentored on the footy field have gone on to uni or fruitful careers, confirming her belief in the power of sport to change lives. “If you could align sport with some of the other programs we have, I just see we could change a lot of the outcomes for young people and families in remote communities,” she says. One way or another, she’ll be grabbing the ball and getting it on the boot.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout