Abuse and anger: Family’s demand for answers over Charli’s toilet block death

A teenager caught in a toxic relationship was found dead in toilet block. Her tragedy is one of six deaths exposed by an investigation into “a national shame”.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

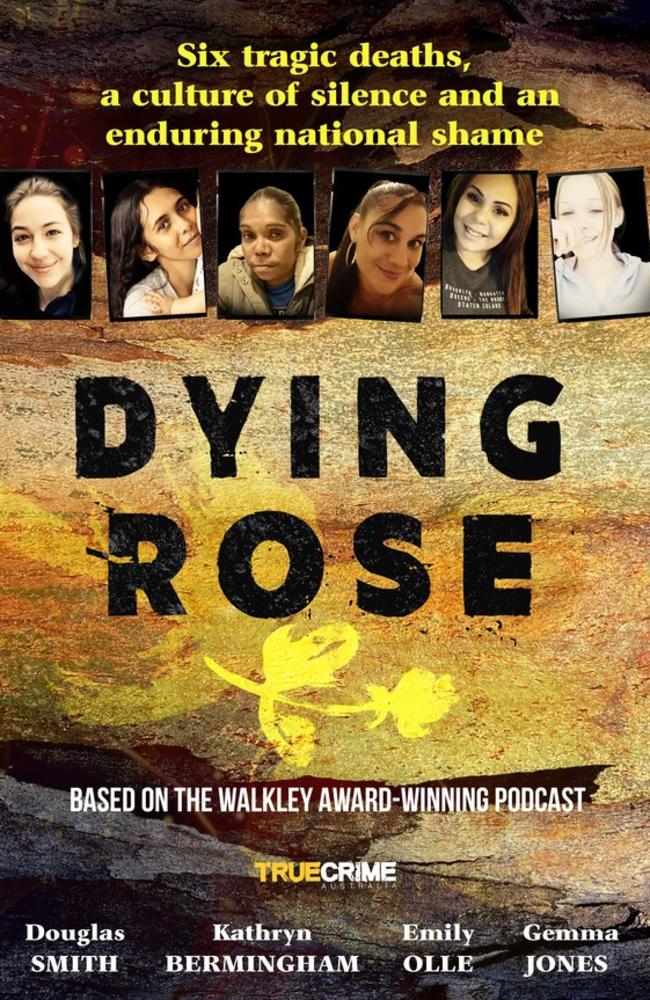

Six women found dead, each case swiftly declared a suicide – but leaving unanswered questions about domestic violence, abusive relationships, police processes and racism.

With five of the six bereaved families still refusing to accept the suicide conclusion, the cases are being examined in a new book: Dying Rose, named for the award-winning podcast investigation into what has been called “a national tragedy”.

This is the story of the youngest victim: 17-year-old Charli Powell, discovered lifeless in a grotty men’s toilet block.

DYING ROSE: Death that exposed a national tragedy

“Please help me!”

It was 4am on Monday 11 February 2019 when Stephen* was jolted awake by a frantic knock at the door.

Stephen, then 42, lived in the suburbs of Queanbeyan, a regional New South Wales town near Canberra. It was a quiet, residential area and any disturbance at night was unusual.

Wearing only his underwear, Stephen got up and cautiously approached the front door. On the other side of the locked screen door was a young man – somewhere between sixteen and nineteen, Stephen guessed – with a baby face and dark hair and eyes.

“I think she’s killed herself,” the young man said.

Stephen was wary but the youth seemed to be in shock and suffering genuine grief.

“He was just very upset and obviously needed help, so I wasn’t going to second-guess that,” Stephen said later. He put on a dressing gown and ugg boots, went outside and followed his late-night visitor to Freebody Reserve, about fifty metres away.

The recreational reserve was popular during the day, but late at night it was deserted.

The young man led the way to a men’s toilet block at the edge of the reserve. It was a dingy old freestanding brick block with a concrete floor. There, they met with a confronting sight: a girl was slouched in the doorway, vomit and blood around her.

“I saw the deceased there on the ground,” Stephen later told the New South Wales coroner’s court. “And it was reasonably dark, but I noticed that there was clothing around their neck

and they weren’t moving.”

The young man bent down in disbelief and cradled the girl, saying words to the effect of “She can’t be dead”.

Together, the two men dragged her out of the toilet block and started CPR, until an ambulance arrived. Then, as the paramedics tried to save the girl’s life, the inquest would later hear, the young man told Stephen that her family was going to bash him and kill him.

‘SHE FELL IN LOVE HARD’

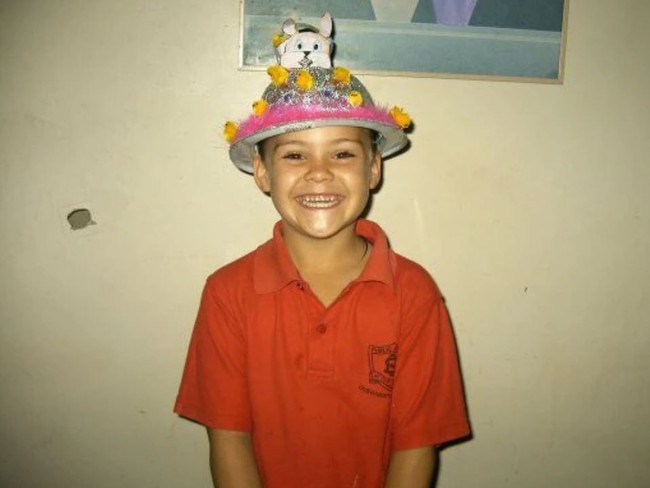

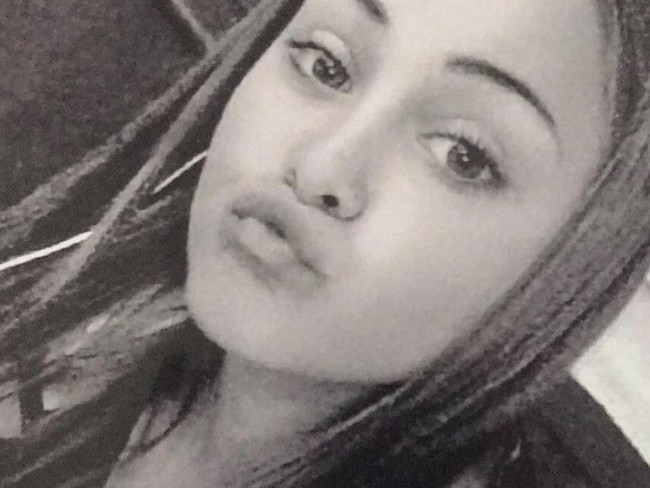

That girl was Charli Powell, just seventeen years old when she died. Born in October 2001 to parents Sharon Moore and Douglass Powell, Charli was adored by her large family and close circle of friends, who say she was vivacious, passionate and full of life.

“She was my second-eldest, and the craziest,” Sharon told the Dying Rose reporting team. “You know, I wonder if she actually knew she was gonna pass away young, because she just lived every day to the fullest. As she walked in the room, I know it’s cliche, but it used to light up, like she just had that personality.”

Charli had grown up in Queanbeyan, on the lands of the Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples, but she was descended from their neighbours, the traditional owners of the plains of central

New South Wales. The Powells, Charli’s father’s family, were Wiradjuri people, and she was proud of that heritage.

Charli had attended Queanbeyan South Public School and then Karabar High School before she left during Year 10. To her best friend and classmate, Kaitlin Sanderson, the word that best described Charli was “fun”.

In October 2018, Charli had started working part-time at KFC. But Sharon said her dream was to be a forensic scientist. She wanted to help solve crimes, and to protect people.

“Growing up through school, she’d been bullied. And so she used to take people who were being bullied under her wing and look after them,” Sharon said. “She was a real good girl.”

In her short life, Charli had her share of challenges. She’d witnessed domestic violence and instability, and by the time she was thirteen, there had been thirteen child-at-risk reports made about her. She had also come to police attention on about fourteen occasions by the time she was seventeen.

Charli had been exposed to drug use; she was reported to have used cannabis regularly and might have used ice on occasion.

A coronial investigation into Charli’s death, launched four years after her body was found, also uncovered allegations of violence by her boyfriend, though he denied it.

Charli had met her boyfriend, whom we’ll call Logan, when she was fifteen. When they first got together, in April 2017, she’d been happy. But before long Sharon began to notice a change in her bright, bubbly daughter.

“She fell in love hard, because it was her first boyfriend,” she said. “But then, I don’t know … he was always calling, like obsessive calling, all the time, constant. I just saw a decline in her mental health. She wasn’t as happy, and she’d come home a bit sad.”

Kaitlin had noticed it too. About six months into the relationship, she said, things started going downhill. “The violence started,” she said. “From there on, it just got worse and worse.”

After one particularly concerning incident, Logan was charged with assault but not convicted – the charges were dropped after Charli died, and he later denied it happened.

Charli would sometimes live with Sharon, and other times with Logan.

“I started to notice she was actually cutting herself, and started self-harming,” Sharon said.

Logan would eventually tell the inquest into Charli’s death that their relationship was “f**king toxic”. The coroner called the relationship “abusive”.

Logan had Charli’s number saved in his phone under the name “slut”, which he said he had probably done after an argument. They fought about both of them cheating, and Logan admitted he used to threaten Charli.

Among the jealous, controlling and abusive messages he sent, one read: I swear to God you slut around on me, I’ll stab ya in ya throat.

DYING ROSE: THE SIX VICTIMS

Logan told the inquest he had not been violent towards Charli at any stage, including in the period just prior to her death.

But the coroner disagreed.

“I do not accept his evidence in this regard,” she wrote in her findings, released in October 2022:

The clear weight of the evidence supports a finding that [Logan] did make threats of violence and used actual physical violence towards Charli during their relationship.

In my view that violence would have been a stressor for her and is likely to have contributed to her state of mind around the time of her death.

In early 2019, Charli decided she was going to end the relationship with Logan for good. But she didn’t find it easy. The relationship seemed to start back up.

On 10 February 2019, the day before she was found dead, Charli had gone to stay with Logan at his mother’s house, not far from her own family home in Queanbeyan. But it hadn’t gone well. At one point, Charli called Sharon, upset.

“They were fighting, and she asked me to go pick her up,” Sharon said. “My car was unregistered at the time, so I borrowed my mum’s car and I rang her back, and I’m

like, ‘I’ll come up, I’ll be there in like two heartbeats, I’ll be there straightaway.’ But she said, ‘No, it’s okay, Mum. Everything’s okay now.’ She didn’t sound okay.”

That was the last phone call Sharon ever had from her daughter.

CONFLICTING ACCOUNTS

In the years that followed Charli’s death, Sharon was able to discover little about what had happened in the final hours of her daughter’s life.

First the distraught mother relied on the police to find out. Then, when police said her daughter had died by suicide – which Sharon found hard to believe – she looked to the New South Wales coroner for answers.

For years, she fought for a coronial inquest, and finally she was successful. But the inquest, which started in March 2022, came and went without giving Sharon the closure she yearned for. She still had so many questions, felt even less certain of the truth, and still felt that no one was listening to her.

By the time the inquest was done, Logan had given three different accounts of the events leading up to the discovery of Charli’s body in the men’s toilet block at the oval: the first to police and ambulance officers at the scene on the day Charli died; the second, eight months after her death, in an “ad hoc” police interview; and the third in evidence given at the coronial inquest.

In her findings, even the coroner noted it was “difficult” to know exactly what had unfolded due to Logan’s conflicting accounts, describing his evidence as “certainly confused and at times inconsistent”.

Sharon’s legal representative, Michael Bartlett, submitted that Logan’s entire account

should be rejected – and the coroner admitted she had sympathy for that submission. She found aspects of Logan’s account, in particular the reason he travelled to the toilets, to have “troubling aspects”.

POLICE COULD NOT EXPLAIN

Logan maintained that Charli had left his home after an argument and that she had called him from the toilet block.

When Logan arrived at the oval, he found Charli hanging in the entrance to the male side of the toilet block. She was suspended by a pair of thin blue women’s jeggings. In evidence, Logan described Charli’s legs as being “curled up”, with her knees bent and her feet behind her. He said he could not see her feet touching the ground.

He said that he had attempted to do CPR before running to a neighbour’s home for help. After that, he said, he called triple-0.

By the time the police arrived, Charli’s body was on the ground, no longer hanging. State Emergency Services crews had set up a large tent next to the toilet block, shielding Charli’s body from view.

When Sharon and Kaitlin asked later that morning how Logan had got her body down, the police couldn’t explain.

Because they hadn’t asked him.

“They didn’t second-guess him at all. They just took everything that he said and just ran with it,” Sharon said.

Sharon found it hard to understand the way police had treated Logan that morning. At the time of Charli’s death, there was a warrant out for his arrest: he was facing charges for an assault on Charli, just across the border, in the ACT. One of the police officers who arrived

at the toilet block that morning recognised him. She knew about the warrant, but not what it was for. Instead of arresting Logan, she told him, “Go home, have a cup of tea, coffee, get physically sorted out and then come back to the police station.”

But he didn’t come back.

It was more than eight months after Charli died that the police caught up with Logan. He was arrested on other charges on 30 October 2019. When the inquest started in March 2022, Logan wasn’t there in person. He was serving a 10-year prison sentence after pleading guilty to seventy-six charges resulting from a year-long crime spree.

BODY FOUND WITH BRUISES

The day after Charli’s body was found, Sharon and Kaitlin went to see her at the funeral home. There, they found that she had a number of physical injuries.

“She had two big bruises on her cheeks, massive big bruises,” Sharon said. “There was a big bruise in between her forehead that was actually raised.”

That bruise was noted in Charli’s autopsy report. Sharon believed that it might have been inflicted by Logan, but he denied hitting her.

Voice shaking, Sharon interjected, “Police just believed it was suicide and that’s what they ran with from the start.”

Police said Charli, who was only 165 centimetres tall and weighed just fifty-two kilograms, had somehow shimmied her way up between two walls in a corner of the toilet block’s entryway until she reached a roof beam.

According to what Logan told police, she’d then managed to sling a pair of thin blue jeggings around that beam.

As far as Sharon knows, no tests were conducted until shortly before the coronial inquest, several years after her daughter’s death, to assess whether those jeggings could or could not have borne Charli’s weight.

“They didn’t open those jeggings until court three years later … they’d never even pulled on them to see if Charli’s weight could hold that,” Kaitlin said. “I knew Charli’s case had been neglected, but I didn’t realise how badly until it all came out in court.”

There was also the question of how Charli had reached the beam.

It was not until well after Charli’s death – again, just before the coronial inquest – that a reconstruction was performed to confirm that it was in fact physically possible for a person of

Charli’s height to reach the beam.

Somehow, though, Charli had also managed to tie the jeggings around the beam – according to Logan’s evidence – while she was on the phone.

“She was on the phone to me when it happened – like, it all went quiet, but I dunno what happened,” Logan had told the coronial inquest.

‘SIGNIFICANT ABUSE’

In her findings, the coroner said she had no trouble accepting that Charli had been subjected to Logan’s rage “on numerous occasions”.

“Her death may well have been an impulsive act, but she had been subjected to significant verbal and physical abuse in the months before she took her own life,” she said. “I have no doubt that impacted on the decision she made.”

She acknowledged that there were inconsistencies in Logan’s evidence about how he found Charli hanging and that his account of events had changed between his initial police interview and examination at inquest.

Ultimately, though, she ruled that Charli’s death was a suicide, shutting down speculation that Logan could have had a hand in her death. She said he did not appear to have been

capable of such a sophisticated pretence.

***

Like many of the other mothers who spoke to the Dying Rose team, Sharon believed that the police response to her daughter’s death was tainted by unconscious bias. She told

Kathryn that Charli was known to police as a “troublemaker” before she died. Sharon thought that history had affected the way the police looked at her death. That was why “no one

listened” when she asked how they could be sure her daughter had taken her own life.

“I can’t get my head around it. She was just a kid. She was seventeen. Why did they not help? Was it because she’s black? I don’t know. I still don’t know. But it’s not right.”

This is an edited extract from Dying Rose by Douglas Smith, Kathryn Bermingham, Emily Olle and Gemma Jones. It will be published by HarperCollins on March 19.

Listen to Dying Rose here or wherever you get your podcasts.

If you, or someone you know, are feeling worried or no good, we encourage you to connect with 13YARN on 13 92 76 (24 hours/7 days) and talk with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Crisis Supporter.

*Name changed to protect privacy

More Coverage

Originally published as Abuse and anger: Family’s demand for answers over Charli’s toilet block death