How an investigation into one woman’s death uncovered five more – and a tragedy on a national scale

When journalists began investigating questions around one young woman’s death, they uncovered five more cases – and a tragedy on a national scale.

How four journalists’ investigation into one young woman’s shocking death uncovered a tragedy on a national scale.

“If you think it’s hard being a white woman in Australia,” Courtney Hunter-Hebberman said, “try being a black woman.”

The clattering of chairs and clinking of glasses stopped, and the marquee fell silent. Hundreds of guests at long tables swung around to see Courtney, up on the stage at the lectern.

Until she said those words, her Welcome to Country had been everything you would expect. She had acknowledged Elders, her language, her culture and how First Nations people care for the land. It was all very familiar. Then, because it was International Women’s Day, she had turned to the subject of how First Nations women are treated.

All anyone could hear was birds chirping in the tall gumtrees outside. Courtney’s final words came in a rush.

“My daughter died and I’ve had no justice. She was only 19.”

Her shoulders slumped, and as she left the stage she looked forlorn. The crowd was still silent at first, then a murmur rose.

Who was this woman who had just bared her soul? And who was her daughter, the girl who had died so young?

Then the afternoon carried on: lunch was served; a motivational speaker took to the stage; a local radio host said and did all the things expected of a compere at a corporate event.

By the time the formalities finished, Courtney was long gone. Her work done, she’d headed home, unaware of the buzz her words had created.

‘GRIEF HIT LIKE A TRAIN’

Gemma Jones, editor of News Corp’s Adelaide masthead The Advertiser, was a guest at the lunch that day. When the speakers had all left the stage, she went around the marquee trying to find Courtney, and then, when she couldn’t, she found the event’s host and asked for Courtney’s number. After hearing her speak, Gemma wanted to know more.

When they talked, Courtney was friendly and warm – if a bit surprised by the interest. She said later she couldn’t believe someone had listened to her and wanted to hear her daughter’s story.

They arranged to meet, and a few weeks later Gemma and political editor Kathryn Bermingham were on their way to visit Courtney at her home in Campbelltown, a quiet, reasonably well-to-do Adelaide suburb not far from the city. Kathryn had recently reported on the death of another young First Nations woman, and there were apparent parallels between that story and what Courtney had said about Rose.

Courtney met them at her door and ushered them down a long hallway into a bright, open kitchen and living room. It was quite obviously a happy family home. A pet dog greeted them, a kitten stretched out in a nearby basket, and young boys were milling around making after-school snacks.

But something about the room struck them.

The presence of Courtney’s daughter, Rose, was palpable.

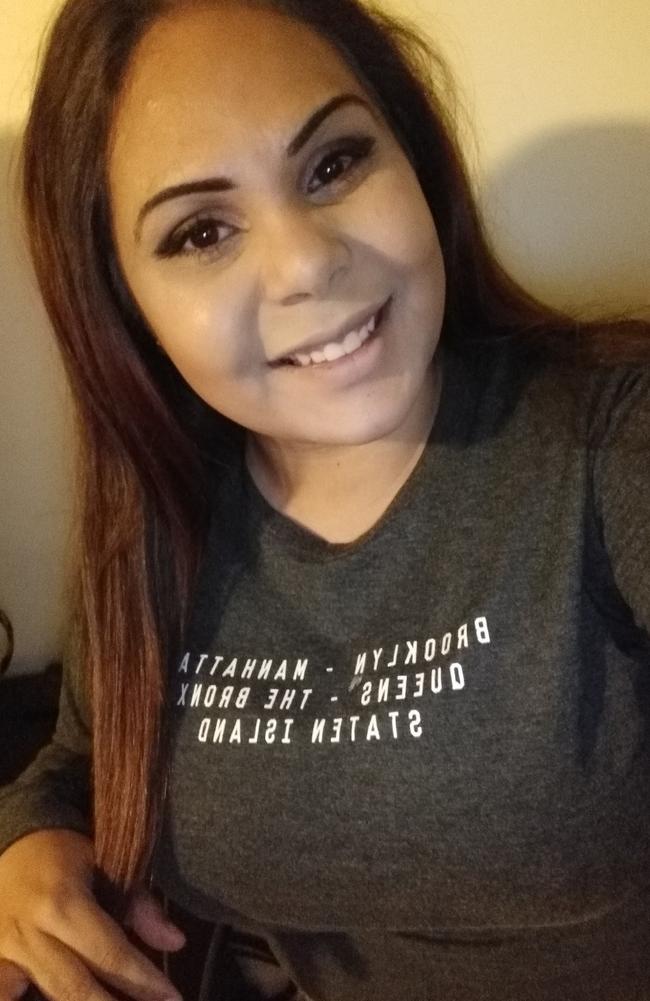

In one corner was a bookshelf stacked with Rose’s belongings and adorned with photos, trinkets, flowers and fairy lights, like a shrine. On the top shelf was a beautiful professional photo of Rose, printed on canvas. She looked barely 19, and so happy she glowed. A smile spread across her face, and her warm brown eyes, so like her mother’s, were staring straight at the camera. A cherubic young boy was on her shoulders, hands in front of his face as if he was playing peekaboo.

On the lounge nearby sat Courtney’s mother, Mandy Brown, there to support her daughter and share her own memories of Rose.

Courtney retrieved boxes from a cupboard, containing all that was left of her daughter’s life. There were receipts, scraps of paper, handwritten notes – snippets of Rose’s final months – along with her old phone, autopsy notes and a few other bits and pieces Courtney had kept in the hope they would all be examined by police one day.

Then the words came tumbling out. Grief, she said, hit like a train at times, but she could talk about her daughter’s death now without crying.

Rose had died just over two years earlier, Courtney said, in December 2019. She was found slumped on a lounge in a tiny shed at the rear of the property she was living in. The police

said it was suicide. This had come as a huge shock to the family, and they weren’t convinced, Courtney said – but when they’d tried to ask questions, they felt like no one was listening.

With the family’s permission, we formed a team to investigate Rose’s death. There were four of us: Gemma and Kathryn were joined by senior reporter Emily Olle and Douglas Smith, who joined the newsroom as Indigenous affairs reporter just as we began our research. Our plan was to produce a podcast, to make people listen. We would ask the questions Courtney craved answers for.

We started with the death of one young Indigenous woman. We could never have known that within months we would be examining five more.

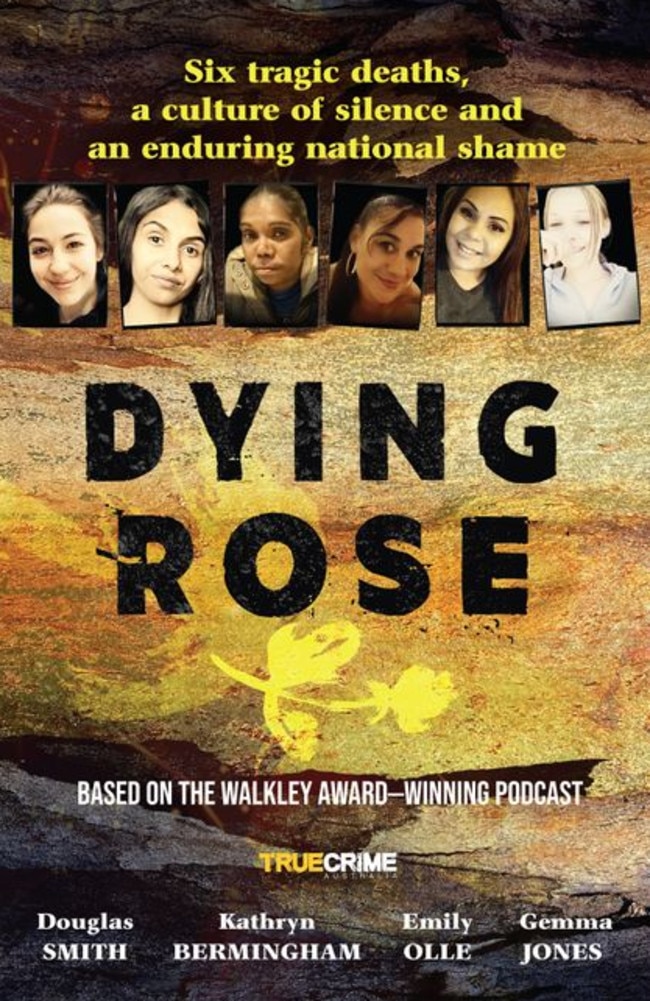

At first we were focused exclusively on Rose Hunter-Hebberman’s story, and we named the podcast for her: Dying Rose. The scope of the project expanded rapidly, though, as we learned about other young women who had died in similar circumstances. The same sequence of events played out with heartbreaking regularity: while we were investigating one woman’s story, we would uncover another.

Courtney led us to some of these stories, and Douglas to others. In each of the cases we investigated, a young woman had died suddenly and unexpectedly, and her death had been ruled a suicide, leaving her family struggling to understand, confounded by their grief.

These young women were all daughters, all sisters. Some were young mothers.

All were let down in a multitude of ways before and after they died, but almost no one seemed to have noticed.

Their names were Rose, Charlene, Lasonya, Lyla, Shanarra and Charli.

‘NO ONE WAS LISTENING’

We started by travelling the country, interviewing the women’s families. Emily joined Kathryn on regular visits to Rose’s mother Courtney, each visit leaving them with more leads to chase up. Doug spent hours with Charlene’s family, recording her parents and brothers and sisters.

One after another, the families told us almost the same story. Only the details of how their daughters had died were different.

Charlene Warrior vanished from the blink-and-you’d-miss-it service town of Bute, SA. She’d gone there to pick up her baby daughter and hadn’t returned. Charlene’s desperate sister told police she would never just disappear like that, but it was more than a week before they started their search for her.

Lasonya Dutton’s uncle discovered her decomposing body in the backyard of the family home in Wilcannia, in outback NSW. Police told the family her body had been lying there, just outside the kitchen window, for days – yet none of them had seen it.

Lyla Nettle was discovered in a dusty creek bed at Bolivar, north of Adelaide. Even the police acknowledge the location and position of her body were unusual. Lyla’s mother doesn’t understand why they say her death was a suicide, because the pathologist’s report didn’t rule out the involvement of another person. Lyla had recently found work in Queensland and was about to move there for a new start.

Shanarra Bright-Campbell attempted suicide in the backyard of her mother’s flat in Alice Springs. When the police arrived, her brother was distraught: they needed an ambulance, he said, not police. He was arrested and dragged from the house as his mother shouted that her daughter was dying and needed help. He was not charged with an offence.

And Charli Powell was only 17 when she was found dead in the men’s toilet block at a sports field in Queanbeyan, just south of Canberra. Her family feel that the police failed to ask even the most basic questions about how Charli came to be in the toilet block and what had happened to her.

One way or another, the families all said the same thing: they felt the police had been too quick to judge. “Aboriginal, mental health issues, young woman, must be suicide.”

Only Shanarra’s family accept that verdict without any question. The other women’s families remain uncertain – and even in Shanarra’s case, her mother wonders if her daughter could have been saved, had the police responded differently.

The families all felt that authorities hadn’t taken their concerns seriously. In their view, police had failed to properly investigate their loved ones’ deaths or consider crucial evidence.

We were struck every time by the painful questions they’d been left with.

Questions about how their loved ones had died. About what had really happened, and who was responsible. About the progress of police investigations.

They wanted to know more, to understand. They wanted proof. But no one would answer their questions, they said. No one was listening.

“Why will no one listen to us?”

They asked this question over and over.

‘DISTRESSING, EVEN HORRIFYING’

In the course of our investigation, we spoke to witnesses and officials, although it was frustratingly difficult to find anyone in authority willing or able to consent to be interviewed.

At the same time, we gathered all the available evidence we could.

Early on, we collected post-mortem reports. Their language was cold and clinical, without any emotion, yet they provoked so much heartache. Here were young women undergoing autopsies that showed them to have been in perfect physical health prior to their deaths, each reduced now to a list of body parts, all carefully weighed and measured by pathologists who had examined them from head to foot to determine an official cause of death. The physical detail was sometimes distressing, even horrifying.

We spent nearly 18 months combing through it all, poring over police reports and the interviews we’d done, looking for leads, trying to understand how these women came to die.

We leaned heavily on the particular perspective and experience of Douglas, a Kokatha man.

For much of the time, we were sequestered in an audio recording room, away from the noise and bustle of the busy newsroom. At the end of each week, we’d meet to brief each other on developments. The mood was usually sombre, and at times we would be rendered speechless by what the others had learned.

The stories we uncovered were shocking – but what we found particularly disturbing, as reporters, was the lack of attention they’d received. These women had died in circumstances that were hard to fathom, yet their stories hadn’t received wall-to-wall media coverage. Their deaths weren’t seen as out of the ordinary enough to interest the public or play on its sympathies. To the women’s grieving families, it seemed, understandably, that no one really cared.

But we did. And as we worked – and thanks to the generosity of the young women’s families – we were able to investigate an even bigger story.

Each of the young women’s deaths that you will read about in Dying Rose was a tragedy for those who loved her. Together, they reveal a tragedy on a national scale, one that should have us all demanding answers.

This is an edited extract from Dying Rose by Douglas Smith, Kathryn Bermingham, Emily Olle and Gemma Jones. It will be published by HarperCollins on March 19.

Listen to Dying Rose here or wherever you get your podcasts.

More Coverage

Originally published as How an investigation into one woman’s death uncovered five more – and a tragedy on a national scale