Groote Eylandt aims to cut reoffending by a third through Anindilyakwa Healing Centre

A remote Territory island hopes to reduce reoffending rates by 30 per cent by bringing prisoners back on Country. See why this could be the future of local justice reforms.

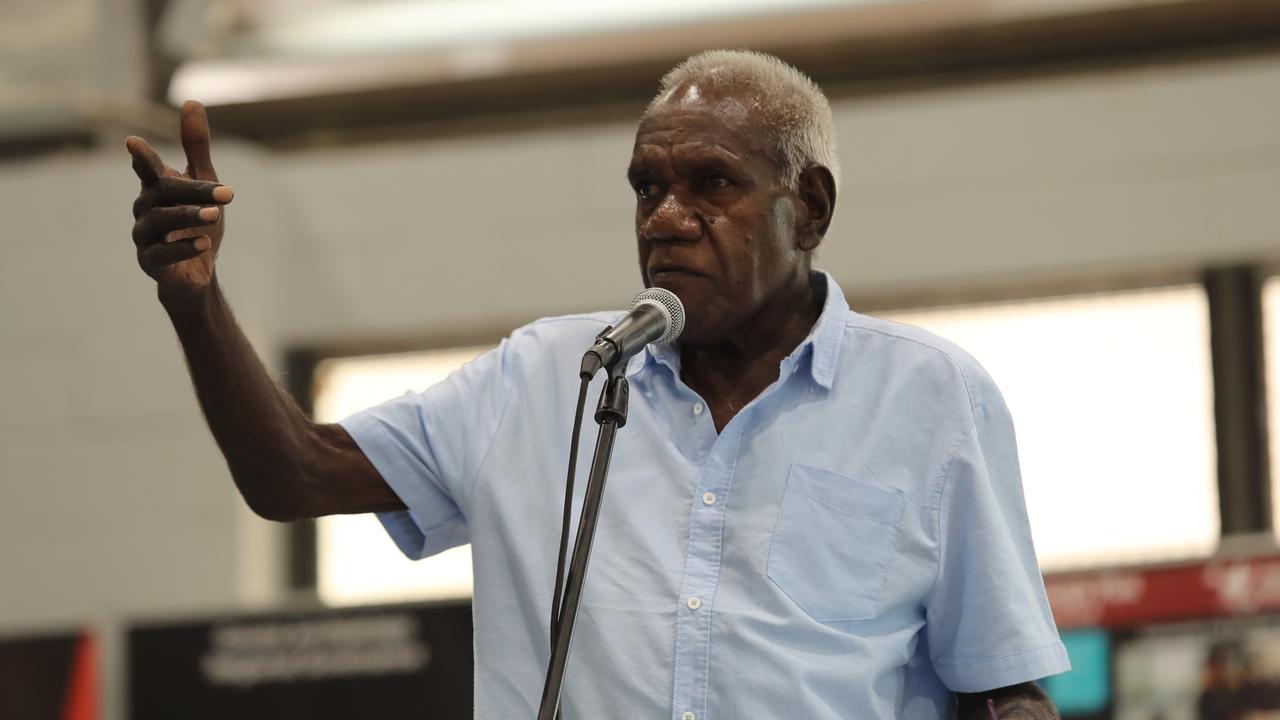

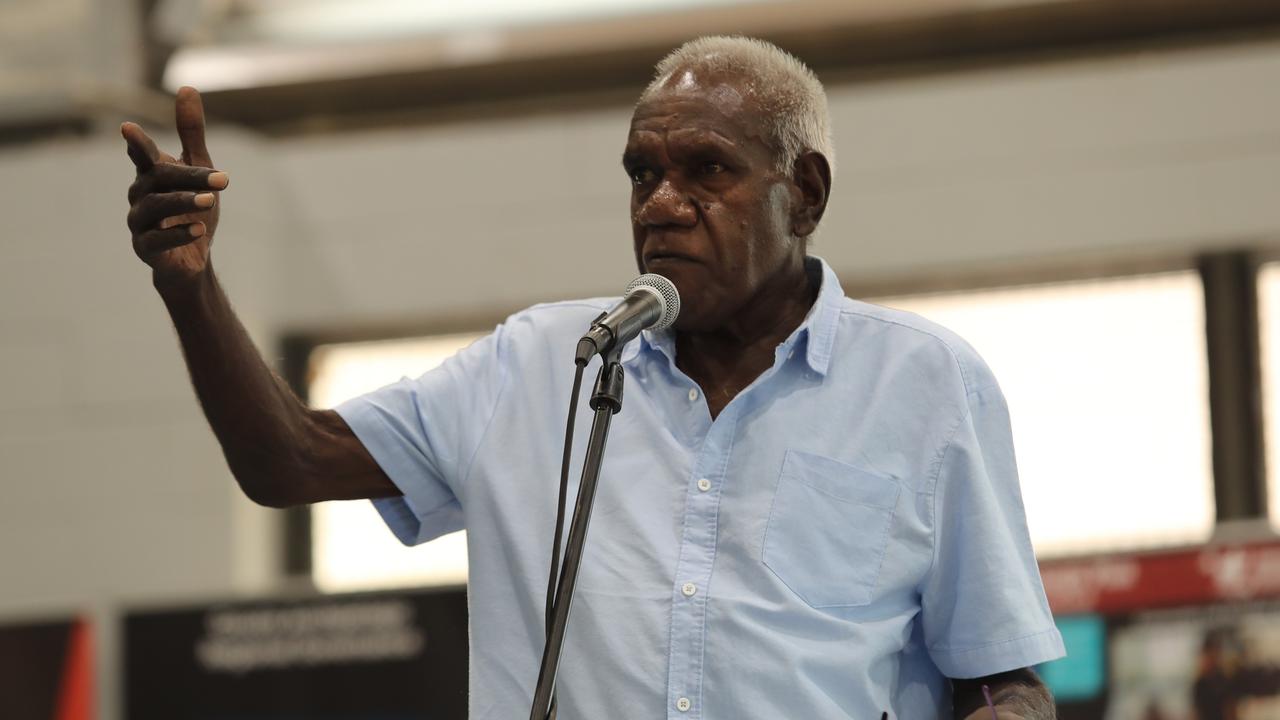

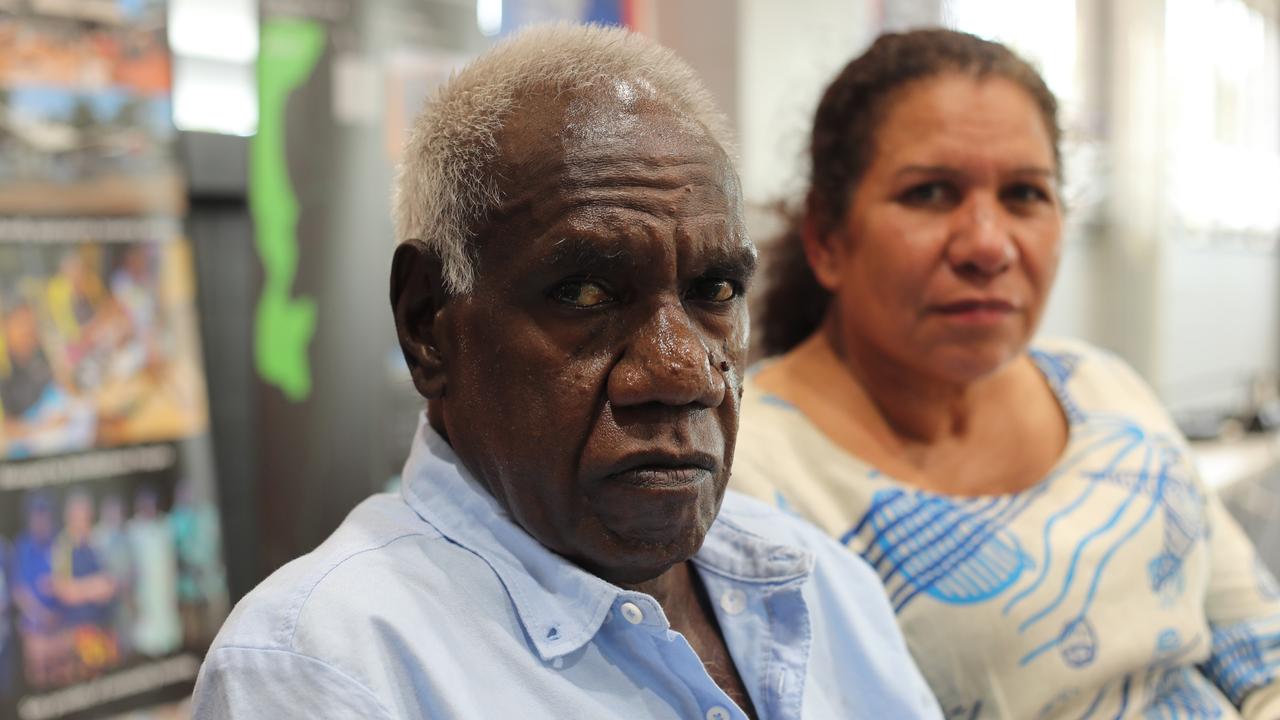

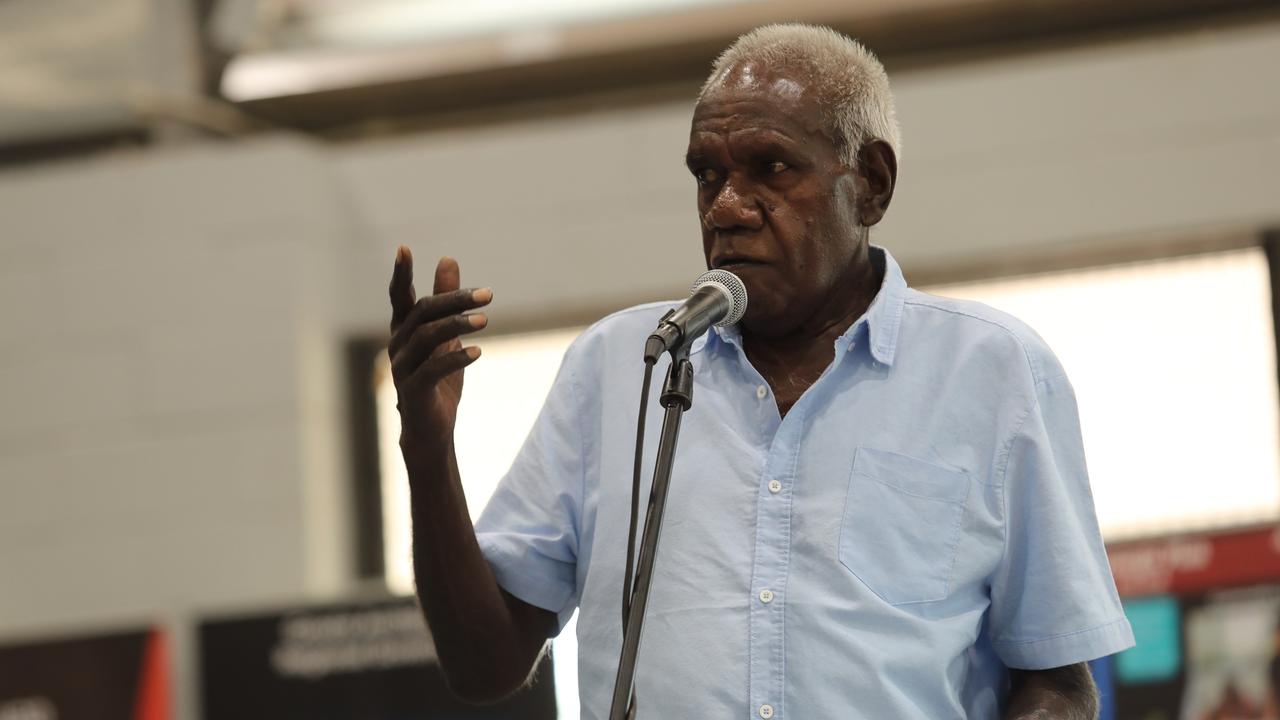

At 61-years-old Tony Wurramarrba has seen generations of young men and boys lost to cycles of crime and alcohol, before being shipped off 644km away to a cell in Holtze.

The Senior Traditional Owner’s voice strains as he remembered how many Groote Archipelago men had been caught up by police and spun through the courts before stagnating in prison.

“In the Balanda (non-Indigenous) justice, they didn’t cope well. They’re more used to the life outside,” the Anindilyakwa Land Council chair said.

“When they do leave, it causes a lot of stress to the mothers, grandmothers, the young ones.”

Thinking back on his own father, Mr Wurramarrba knows what these young men were missing: structure, discipline and hope.

“My father was a much better man than me,” he said.

“My father, he gave me some responsibilities, and that’s what kept me in line.”

In the 1980s Groote Eylandt was in the midst of an imprisonment epidemic, with the region of 2000 people recording a prison rate eight times higher than the Territory average, and 25 times the national rate.

Mr Wurramarrba said his brothers were almost among those trapped in the system.

“But my father didn’t lose hope for when they got out of the cells,” he said.

The Bickerton Island man said his father and brothers returned to their Country: “That’s where the healing started”.

For the past six years, Mr Wurramarrba has been fighting these same practices to be recognised within the Territory’s justice system.

Last week, that dream was realised as the first two Groote Eylandt young men were sentenced to the alternative to custody facility: the Anindilyakwa Healing Centre (AHC).

Surrounded by Elders from the 14 clans of the Groote Archipelago last week, Mr Wurramarrba celebrated the return of the island’s community court, and its new law and justice group.

Delayed barges, bogged dirt roads, and shipments mix-ups to one of Australia’s most remote islands had put the AHC behind its construction schedule, but many in the Anindilyakwa Land Council remain optimistic the 16-bed facility will open by late March.

It is estimated that once the second stage of construction is complete, half of the Groote Eylandt men in prison could be brought back on country.

Mr Wurramarrba said the Drug and Alcohol Services Australia run-facility would allow wayward young men to “see things differently”.

“We have to show them that it will come to a stage where they will become the Elders,” Mr Wurramarrba said.

“Give the responsibility back to the young ones, a little responsibility goes a long way.”

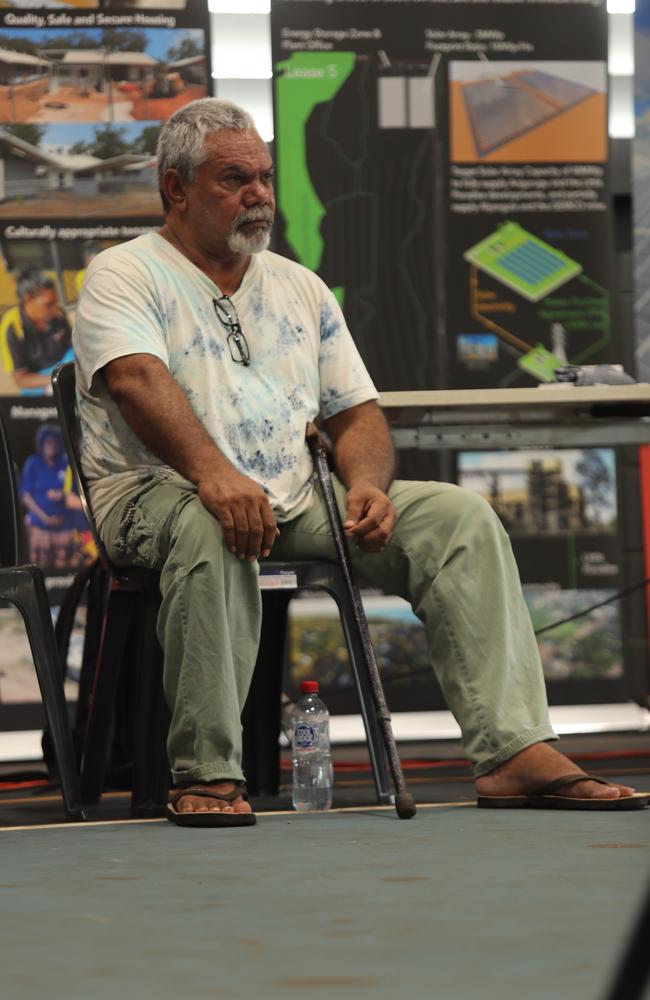

Standing in the still incomplete AHC site, Groote resident Philip Collin said it would also help men aged 17-25 reconnect to their mothers, aunties, wives, girlfriends and children.

“In Holtze, they go in and serve their time and come out worse probably,” Mr Collin said.

“You were flown out and your family wouldn’t see you for six months.

“So now they’ll return to a happy, healthy family.”

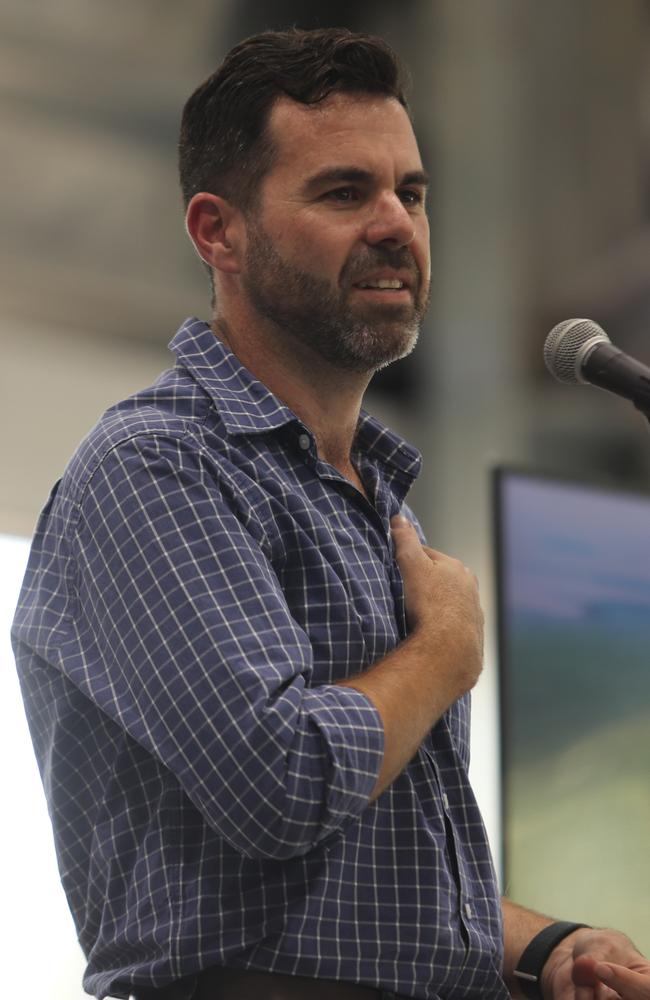

Aboriginal Justice Agreement director Leanne Liddle said touring the centre and speaking with Anindilyakwa leaders was living proof that “amazing things that happen when we work together, and you let Aboriginal people lead and thrive”.

Ms Liddle recalled how six years ago she faced the Elders, who demanded a community court, a law and justice group and an alternative to custody centre.

“I remember walking away going ‘how am I going to deliver all that?’. But we did it,” she said.

Ms Liddle said a youth program out of Groote had reduced reoffending by 95 per cent, with the new AHC predicted to cut adult male reoffending rates by 30 per cent within just 18 months.

The AJA boss said there should be a law and justice group in every Territory community, with similar groups not far behind in Maningrida, Kintore and Yuendumu.

“You will see a decrease in reoffending, you’ll see a decrease in the prison numbers — it’s not rocket science.”

“It’s the community taking control, ownership and accountability and responsibilities so that their people can make better decisions.”

Arnhem MLA Selena Uibo said the $13m Groote Archipelago justice investment was a testament to the local leadership who were ensuring that “culture drives future aspirations”.

“Local decision making has never disappeared for our people. It has been muddled and mixed from the other systems that have come over the top,” Ms Uibo said.

As the Local Decision Making minister spoke, the Groote Archipelago Elder women doted over her five-month-old son Phoenix.

“These old people they never think about themselves … they’re always thinking about kids, grandkids, and great grandkids and their future,” Ms Uibo said.

“We come back to the table to make sure its what the future of our kids need, and what they deserve.”

With plane-loads of politicians, corrections, police, and court bureaucrats landing for the centre’s opening, Mr Wurramarrba chuckled saying he had never seen so many strangers on his island.

But this was a recognition of how his people in a distant corner of the Territory were leading the way for culturally-informed justice.

“We were here before the Makassan, before the missionaries, before the mine.”

“We are not starting something new, we are going back to something we have done for the past 60,000 years.”

IN PICTURES - New justice initiatives for Groote Archipelago