Matt Cunningham opinion: Local decision making paying dividends on Groote Eylandt

An alternative to custody facility on Groote Eylandt will mean young people who commit less serious offences can be dealt with at home, not sent to prison in Darwin, writes Matt Cunningham.

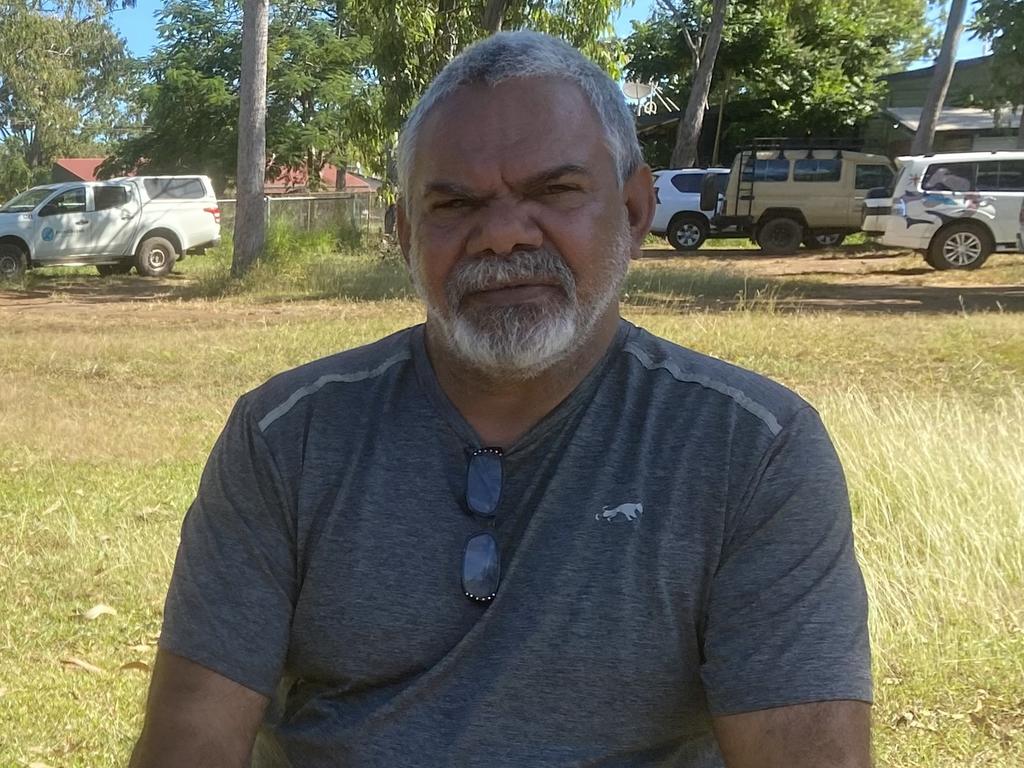

Matthew McKenzie sits on a rock outside the council office in Angurugu on Groote Eylandt. He’s seen a lot of change here over the past five decades or so, some of it for the better, much of it for the worse.

For 60,000 years the 14 clans of the Anindilyakwa people had the islands of the Groote archipelago to themselves.

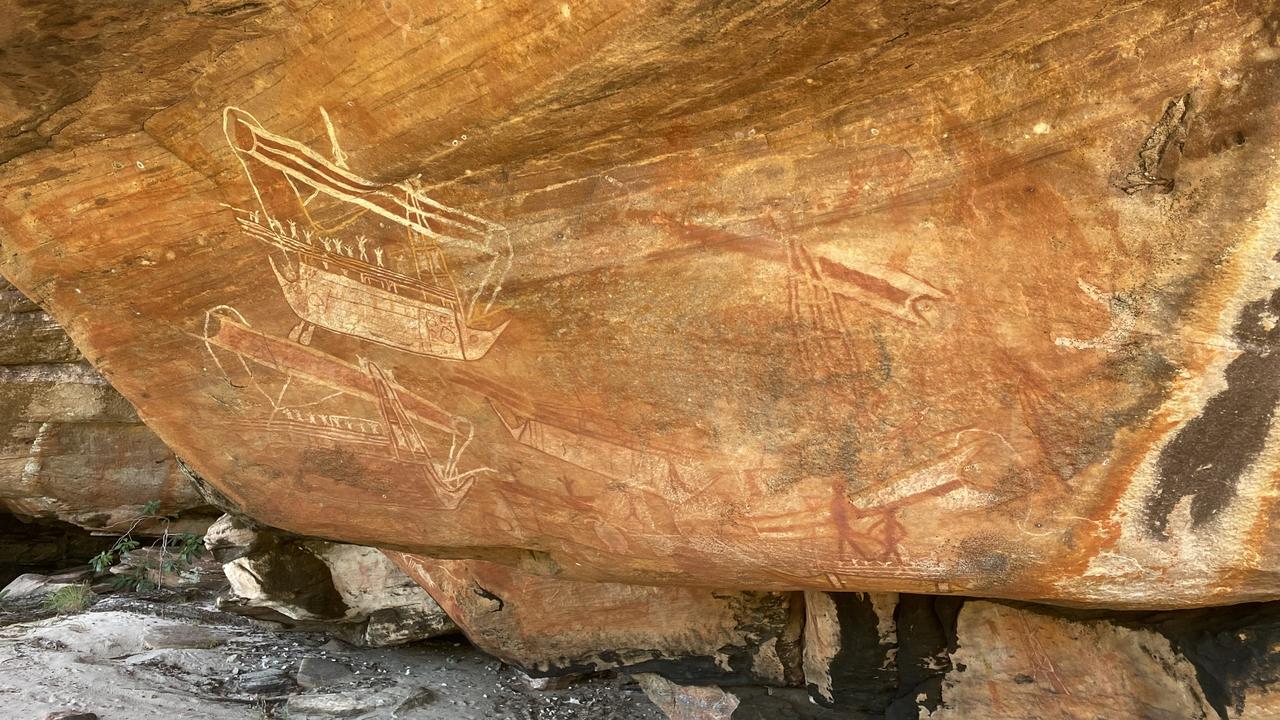

For a few hundred years they traded with the Makassans, exchanging technology and trepang. These exchanges are documented in the ancient rock art that sits still untouched at a sacred site along the coastline.

The first white missionaries only arrived 101 years ago.

In 1964 the Groote Eylandt Mining Company opened a large manganese mine near Angurugu. Mr McKenzie says the mine has been good and bad for his people. It brought economic prosperity but also the curse of sit-down money.

Today Mr McKenzie, who helps run the Anindilyakwa Land Council’s Community Justice Group, is seeing more change — and it’s change for the better.

The Anindilyakwa people are hellbent on creating a better life for future generations.

Almost 10 years ago, the ALC, under chairman Tony Wurramarrba, decided they wanted to take greater responsibility in how royalty money was distributed.

They were sick of seeing continued failure in education, justice, housing, health and economic development.

In 2018, the ALC signed the first Local Decision Making Agreement with Northern Territory Government.

Today, that idea is starting to pay dividends.

Mr McKenzie says there are currently no youth from Groote Eylandt in detention.

“We rather talk amongst each other here and fix the problem here, instead of getting someone out from mainland or somewhere,” he says.

“It’s better fixing the problem here, ourselves.”

The Community Justice Group is creating an alternative to custody facility on Groote Eylandt, so that young people who commit less serious offences can be dealt with at home, not sent to prison in Darwin where they often stray into more trouble.

But justice is not the only area where the Anindilyakwa are taking control of their own affairs. They’re building their own homes, creating their own jobs and even starting a new mine on Winchelsea Island.

Plans are being made so that when GEMCO ceases operation the people on the Groote archipelago will be able to stand on their own feet.

They’re creating new jobs for locals in aquaculture, tourism, land and sea management and at the Winchelsea Island mine.

Employment at the ALC has increased from 36 in 2012 to 173 in 2022.

These jobs mean a better future for people like Renato Marocchini, who spent years in prison in Darwin but is now working as a trade’s assistant building infrastructure for the island’s aquaculture project.

Mr Marocchini is turning his life around through real employment and hopes others can follow his path.

“I’m trying to encourage my family members, community members, with learning these new skills,” he says.

“So we have the skill sets to be able to take jobs back so we’re not becoming dependent on outsiders — and I think that’s a real big thing for my people.”

On Bickerton Island they’re building a new bilingual, independent boarding school to address poor school attendance rates and give kids from Groote the opportunity to continue their education close to home.

“Education is the key to our children,” says Ida Mamarika, the chair of the new school’s board.

“I need my kids, my people, to go to school every day, to learn education every day.”

Life’s not perfect on Groote Eylandt. You only need to drive the 20km from Angurugu to the mining town of Alyangula to see the gap in living standards that exists between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

But this community is showing that things can change for the better. And they’re not waiting for someone else to do it. They’re doing it for themselves.