Hidden skeletons found in Egyptian pyramids reveal surprising historical twist: ‘Counters the traditional narrative’

Archaeologists have long theorised that Egyptian pyramid tombs were reserved for the elite — now, a new discovery may well turn that theory on its head.

Archaeologists have long theorised that Egyptian pyramid tombs were reserved for the elite. However, analysis of skeletons belonging to “extremely active” people might prove that they were dead wrong — and that poor physical labourers could’ve been interred there as well.

These findings, which were published in the Journal Of Anthropological Anthropology, could reshape how we view these ancient mausoleums.

“I think we have assumed for far too long that pyramids were just for the rich,” declared study author Sara Schrader, an archaeology professor at the University Of Leiden, Netherlands, according to New Scientist.

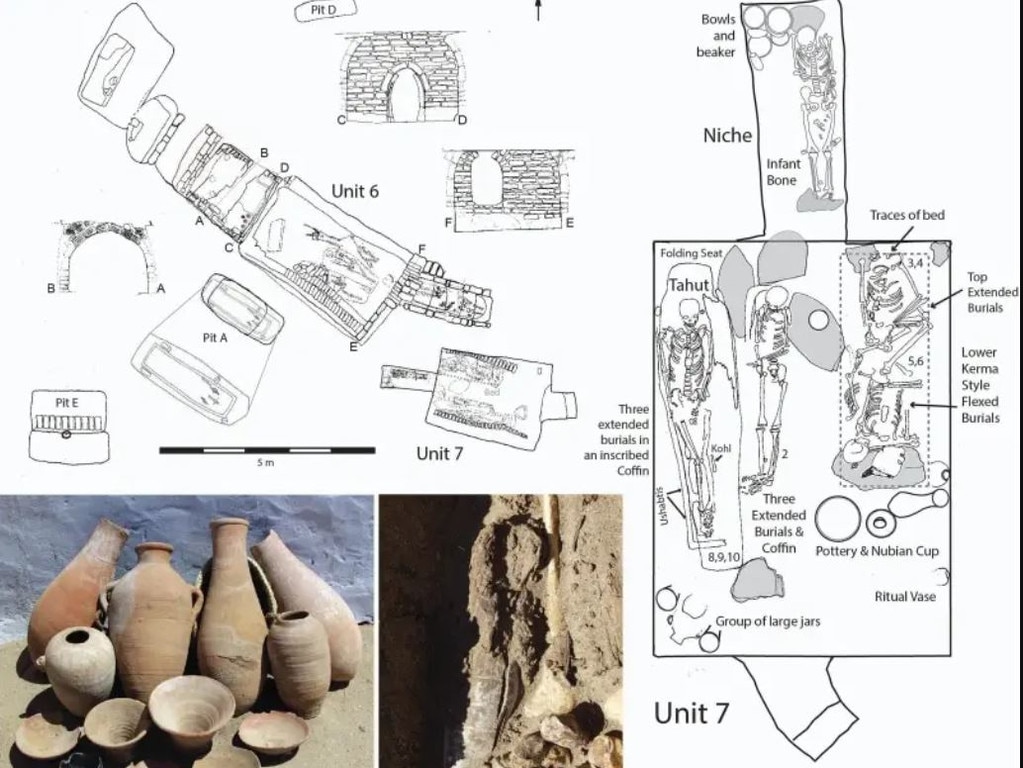

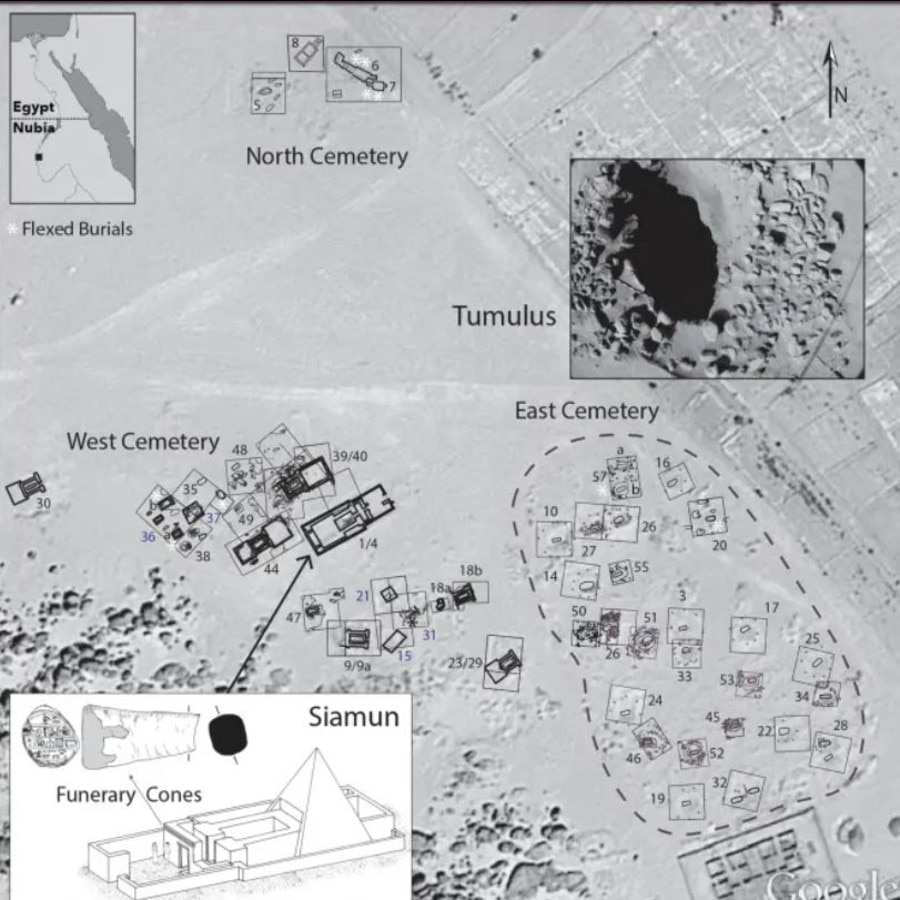

She worked for over a decade at the Tombos excavation site in South Sudan where archaeologists discovered at least five mud-brick pyramids containing pottery along with the aforementioned human remains.

This region was under Egyptian control 3,500 years ago when the civilisation was at its zenith, but by this time, their aristocracy no longer favoured pyramids as postmortem quarters — even though the Egyptian nobles still preferred them.

Schrader and her colleagues analysed the remains at each pyramid, specifically focusing on subtle marks on the bones where muscles, tendons and ligaments were once attached so they could determine the level of physical activity.

The team noted that some remains belong to people who had done very little physical activity during their lifetimes while others had been very active.

From this, the team deduced that “pyramid tombs, once thought to be the final resting place of the most elite, may have also included low-status high-labour staff,” per the study.

They were operating under the theory that the low-activity individuals must have lived in luxury while those with signs of wear and tear had a gruelling life of labour, the Daily Mail reported.

“If these hardworking individuals are indeed of lower socioeconomic status, this counters the traditional narrative that the elite were exclusively buried in monumental tombs,” concluded the team.

They suggested that the higher-ranking individuals had specifically commissioned these pyramids for “themselves, close family members, and servants/functionaries,” perhaps under the belief that the latter could continue to serve the former in the afterlife.

Of course, some experts have floated alternate theories for the mixed-class burial.

UK Egyptologist Aidan Dodson suggested that the high-activity individuals could have been nobles who exercised to maintain their status.

However, Schrader deemed this explanation suspect given the abundant evidence from other sites indicating that elites and non-elites had differing activity patterns.

She also threw cold water on a more sinister theory behind the postmortem status mingling.

“[Human] sacrifice had occurred in the region about 500 years prior,” she said, before noting that “there’s really no evidence for it by the time “Tombos was under ancient Egyptian control”.

Ultimately, the team concluded that digging deeper always brings the truth to light.

“With continued excavations, dating, and biomolecular analysis, interpretations of lived experience in the past can be completely altered,” they wrote.

This article originally appeared on the New York Post and has been republished with permission