Truth about doomed Titan sub revealed

It was supposed to be the ultimate innovation to give passengers a safe birds-eye view of the Titanic wreck, but there was a glaring problem.

It was supposed to be the ultimate innovation. A modern marvel combining advanced materials to offer paying passengers a safe birds-eye view of the infamous wreck of the SS Titanic.

It wasn’t.

Instead, marketing hype and optimistic engineering are being blamed for condemning the passengers of the submersible Titan to death.

One was its owner and builder, OceanGate chief executive officer Stockton Rush.

Millionaire businessman Shahzada Dawood, 48, was taking his son Suleman, 17, on the trip of a lifetime.

Airline executive Hamish Harding, 58, couldn’t resist the lure of such a rare opportunity for adventure.

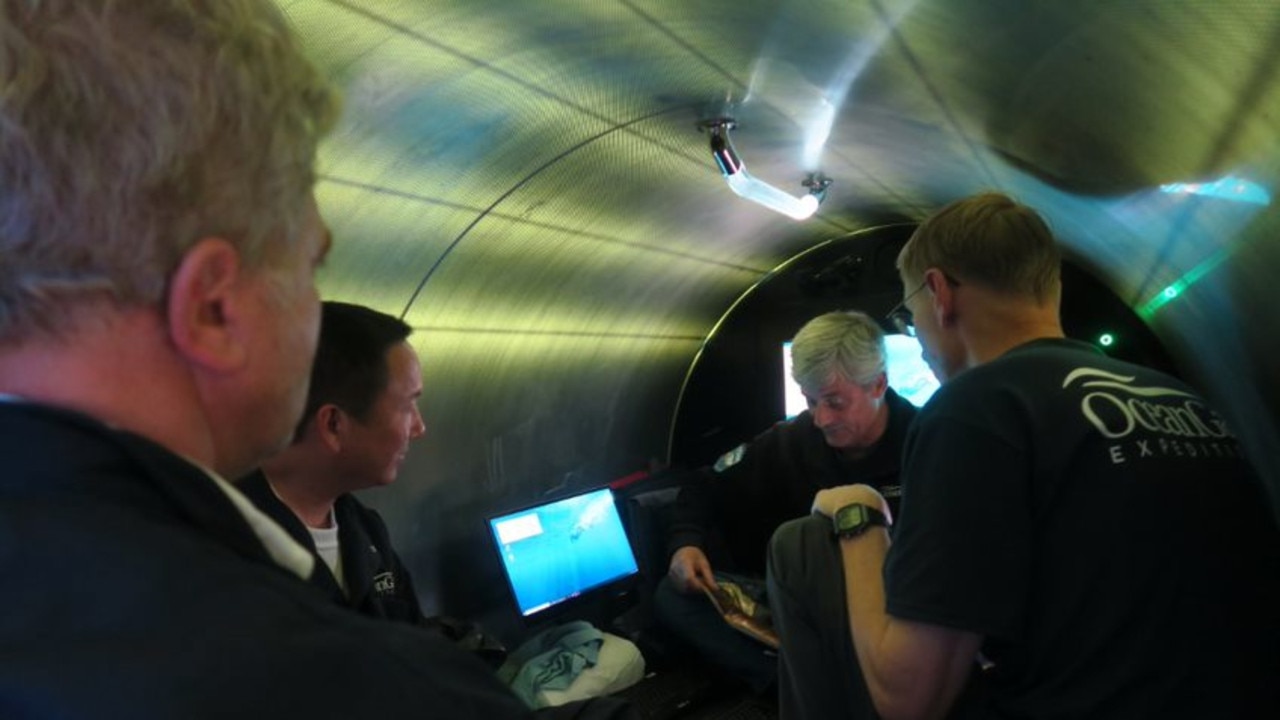

Each had paid about $US250,000 for the privilege to be chauffeured 3.8km beneath the Atlantic’s surface.

Also killed was the Titan’s pilot and famous oceanographer, Paul-Henri Nargeolet.

Now, new research is unravelling what may have caused the mini-van-sized submersible to disintegrate under the ocean’s immense weight.

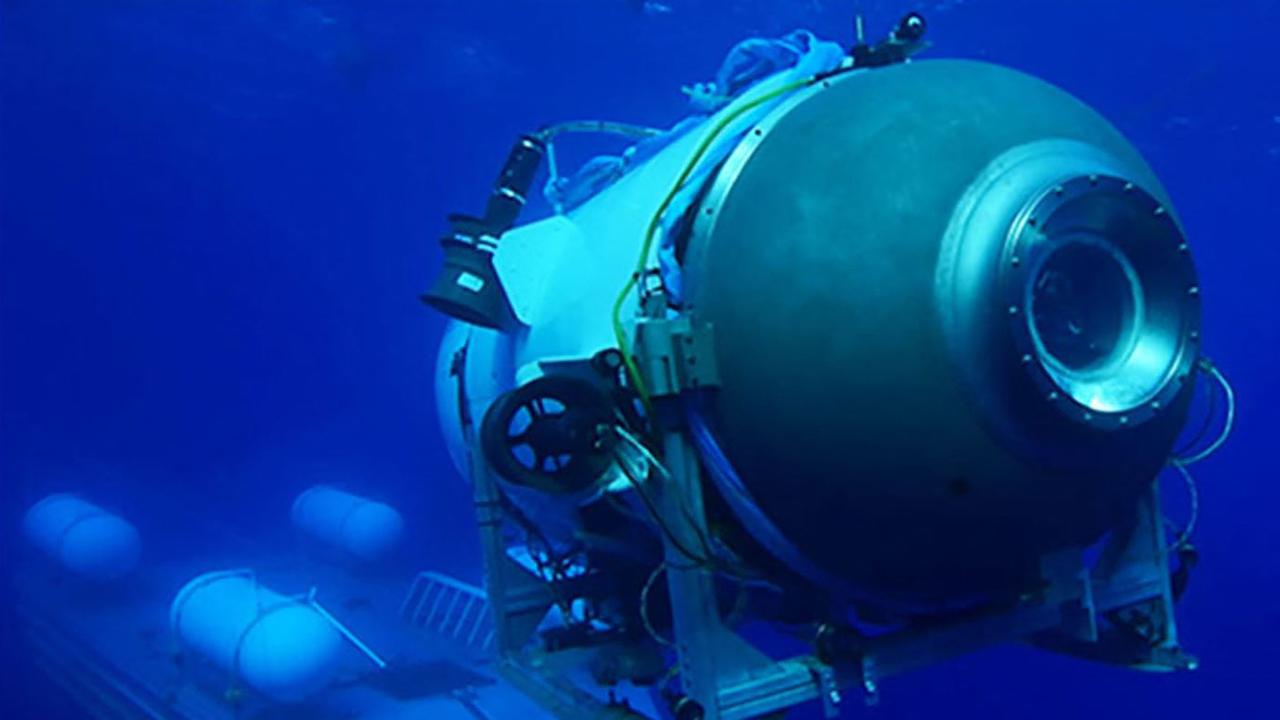

Suspicion immediately fell on the interaction of what naval architects believe are incompatible materials – the transparent titanium viewing dome and the experimental carbon-fibre pressure hull.

But the brittle characteristics of the carbon fibre itself presented the risk of a simple bump triggering a chain reaction of fraying strands that could eventually lead to catastrophic failure.

The University of Houston has sought to simulate this.

Detailed physics models powered the computer recreation of how a carbon-fibre cylinder reacts to repeated flexing.

It’s found the tragedy was almost inevitable.

Fraying hopes

A desperate search was initiated some 560km off the coast of Canada’s Newfoundland after an SOS call was received from the Titan’s mothership, Polar Prince, on Sunday, June 18, 2023. It had not heard from the Titan for eight hours.

That sparked a frantic search and rescue attempt.

It was a race against time. The submersible had been carrying enough air to keep its five passengers alive for 96 hours after slipping beneath the waves.

But the chances of them surviving were always vanishingly small. All knew they had most likely died within milliseconds under the immense pressure of inrushing water.

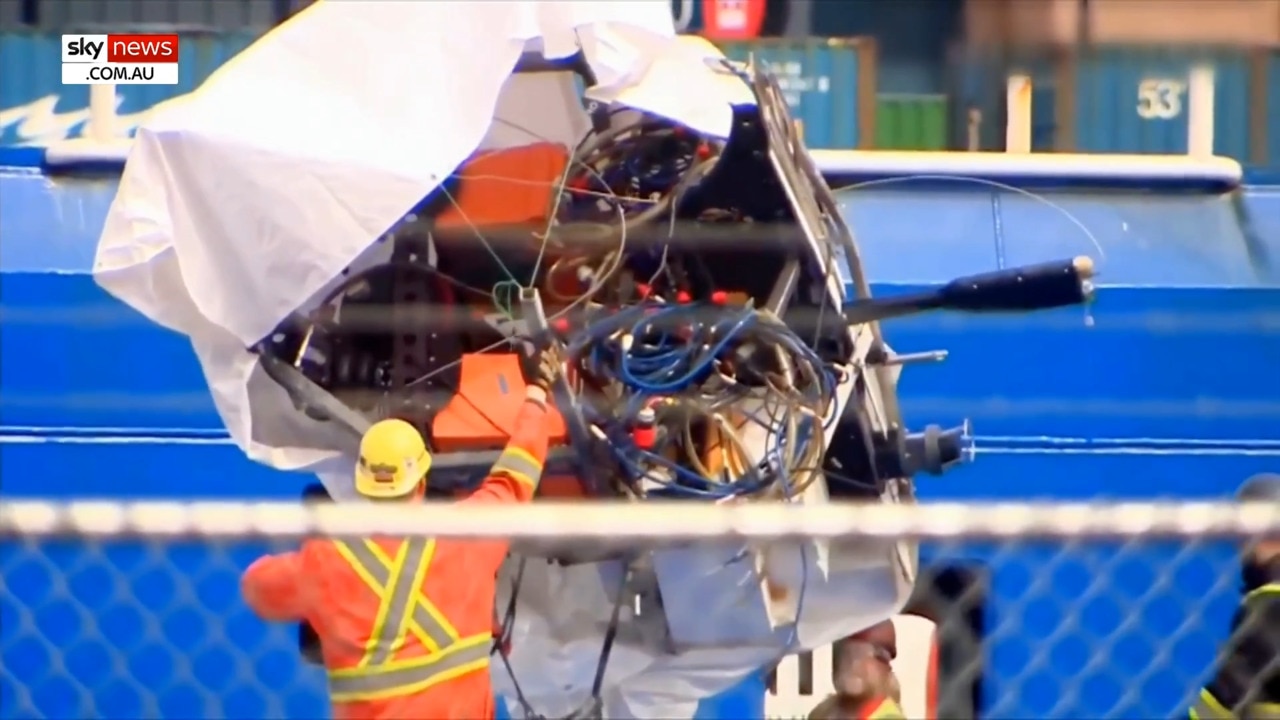

Scattered wreckage from the Titan was eventually found just 500m off the Titanic’s rusted bow. Recovery efforts ended in October.

Forensic investigations are ongoing.

But the University of Houston has published a related research paper in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS).

It didn’t study Titan.

But it did explore how random imperfections in the carbon-fibre manufacturing process would react in a deep-diving hull.

“It is well known that under compression loading, the fibres in such composites are susceptible to micro-buckling and that they may delaminate from the matrix that surrounds them,” says Dr Roberto Ballarini.

“If the Titan’s hull experienced such damage under the extreme compressive pressures it experienced during its dives, then its stiffness and strength would have significantly decreased, and together with the inevitable geometric imperfections introduced during its manufacturing, may have contributed to its buckling-induced implosion.”

Dr Ballarini’s simulations tracked how these imperfections gradually combine to a point where the structure fails.

That means the Titan was getting weaker every time it dived.

It took about 90 descents – including about a dozen to the depth of the Titanic – before the inevitable collapse eventuated.

Foreseeable failure

The finding adds to the weight of allegations that the Titan’s operator, OceanGate, had not fully understood the limitations of the submersible’s design. And that safety standards were inadequate.

Long before the tragedy – in 2018 – a lawsuit was filed accusing the company and its owner of sacking employee David Lochridge for highlighting safety concerns.

“The paying passengers would not be aware, and would not be informed, of this experimental design, the lack of non-destructive testing of the hull, or that hazardous, flammable materials were being used within the submersible,” Lochridge’s lawsuit read.

CEO Rush certainly appeared unconcerned.

In an OceanGate promotional video, he dismissively reads from a disclaimer stating it was an “experimental submersible vessel that has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body and could result in physical injury, disability, emotional trauma or death … Where do I sign?”

One of Lochridge’s allegations, however, now sounds prophetic.

He accused OceanGate of being “unwilling to pay” for electronic scans of the Titan’s lightweight carbon-fibre hull to ensure it had no dangerous imperfections.

He warned such flaws were “visible”.

OceanGate insisted it had developed an in-house acoustic monitoring technique instead.

Sensitive microphones attached to the hull were supposed to “hear” the sound of snapping carbon fibres and provide ample warning for the pilot to surface.

However, Dr Ballarini argues random combinations of imperfections and failures trigger such failures.

“This randomness has profound implications for the statistics of the critical buckling pressure of the shell,” he says.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel