Mount Everest: How I survived the grips of altitude sickness

Placing one foot in front of the other, Oryana Angel made it to base camp as planned. But soon after things started to go terribly wrong.

We’re on our way to Lobuche, a tiny settlement in Nepal 4940m above sea level and just 8.5km southwest of Everest Base Camp.

The wind has picked up and the air is a noticeably thinner as I walk.

We pass a dad and his two sons on their way back down the mountain. The altitude is too much for the younger boy.

As helicopters whiz overhead, I wonder if they are scenic flights or rescues.

Base Camp is just a few hours away, and I’m considering turning around. I’ve come down with a cold, or chest infection, and don’t feel well.

I’ve read about the symptoms of altitude sickness and understand the implications, but after seeking all the advice I could find, not one person who suggested that I descend — other than my husband in Australia — is urging me to turn around.

Considering some 35,000 people do the EBC trek every year and as many as 15 of them die in pursuit, there is a surprising lack of medical advice in this final stretch.

For the first few days it’s T-shirt weather, and we meander through colourful spring wildflowers and rhododendrons in full bloom. Pine forests are lush and green, and there is a steady trail of passing dzo and yaks.

Long swing bridges take us across the clearest water you’ve ever seen running in streams below. We settle into a routine of walking three or four hours in the morning before stopping for the night. It’s not overly difficult, and the Himalayas are everything I imagined and more.

I really notice the change in altitude on day six of the 12-day trek when we are acclimatising at Dingboche — 4410m above sea.

They call this the make or break stop.

The tree line is now below us, meaning the forest can’t grow at this high altitude. Bright prayer flags add some colour to the now barren, rocky landscape.

It’s April, peak trekking season, and the tea houses are full, with some guides and porters even sleeping outside in tents.

There’s an electricity in the air, stories are swapped among the climbers heading to the summit and others who are stopping at Base Camp.

The morning we are to reach Base Camp, my friend goes ahead and our guide walks with me, as I’m having trouble keeping up.

We’re going slow as breathing becomes increasingly difficult, and there is a steady trail of trekkers and porters pilgrimaging along the busy path.

I let those that are walking faster pass by — still I’m surprised by the numbers.

The Himalayan wind is icy, and it feels like we are on another planet.

Frozen glacier lakes, as big as a football field, all of a sudden appear tiny as we march on and on. I’m taking in the unbelievable scenery as best I can, but mostly, I’m focusing on just putting one foot in front of the other.

Every few moments I need to regain my breath. Because we are at high altitude, each step is an effort.

By the time I get to Everest Base Camp, where those climbing to the top spend several months preparing for the summit in tiny yellow tents dotted along the ridge, my travel buddy and guide have already been waiting for 20 minutes.

They are cold and quickly usher me in for a picture before we head back down in order to beat the snow and fog, which is settling in.

Everest is magnificent, but Base Camp itself is an anticlimax.

That night at Gorakshep, the closest place to stay near EBC, it’s not just me feeling crappy.

There are tears and talk of oxygen, lack of sleep and headaches — all to the backdrop of the now ever-present symphony of the khumbu cough or the high-altitude hack.

I crawl into my sleeping bag — it’s well below zero in the room — and I’m still cold even though I’m wearing a ski jacket and beanie.

A few hours later I wake up feeling terrible. I’ve got a headache that won’t go away despite taking a combination of painkillers, I’m dizzy and find it difficult to find my way back from the bathroom.

My friend goes downstairs to get help, and a huddle of guides and locals clamber into our room around midnight. They say my oxygen saturation is 60, or even below, and my heart rate is high.

The signs aren’t good, but no one knows what to do.

I’m already taking acetazolamide as a preventive, and someone suggests another dose. We’re not confident it will do anything.

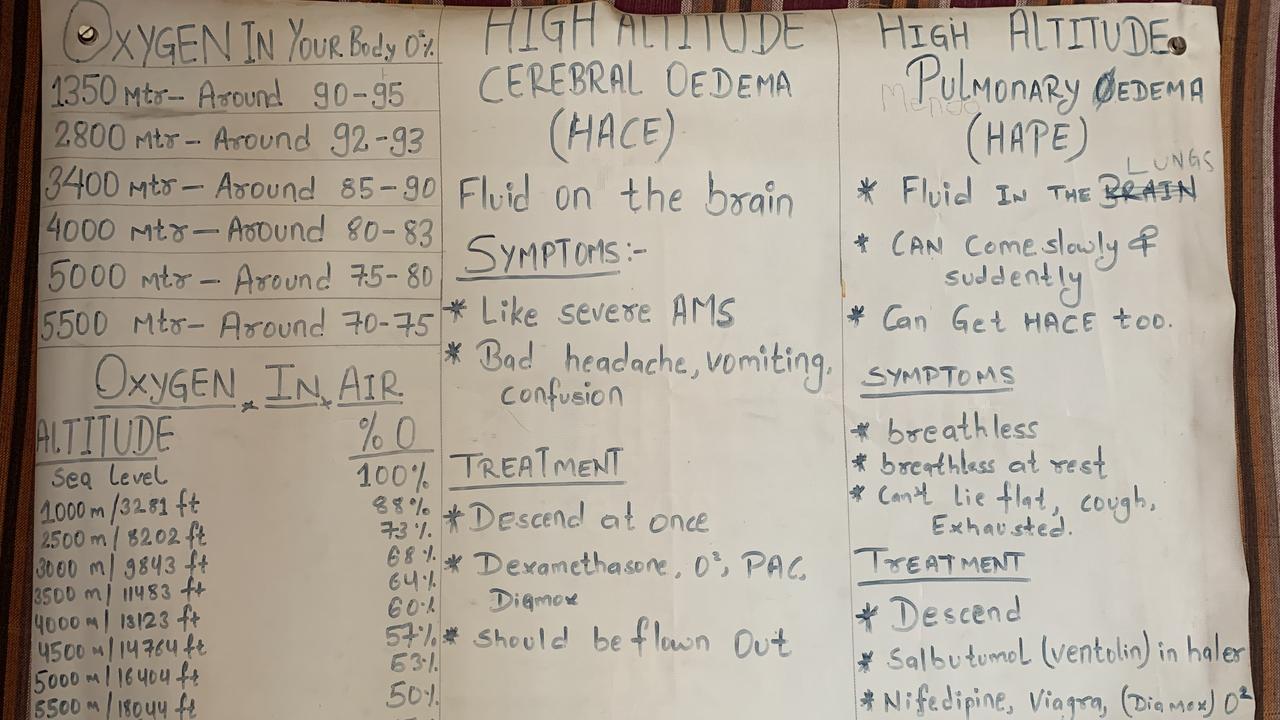

I recall a hand-drawn sign on the back wall of one of the tea houses we had stayed in.

It listed the symptoms of high-altitude pulmonary oedema (fluid on the lungs) and high-altitude cerebral oedema (fluid on the brain) — both fatal.

It’s hard to imagine this can happen, and I’m terrified, silently praying I will make it safely home to my family.

My guide says the nearest medical clinic, a rudimentary centre run by the Himalayan Rescue Association, is in Pheriche — a two-day walk away.

I wonder if I can make it. We set out the next morning at a slow pace.

After an hour-and-a-half stumbling back along the path, my guide says I have acute mountain sickness, and as soon as we reach phone reception, he organises an emergency helicopter, evacuating me off the mountain.

I feel terrible and frightened, and the thing is, I’m not a tick-off-the-bucket-list kind of person and wonder why no one advised me to go down earlier. It seems like I took a dangerous chance.

The full implications of my situation only hit me in the emergency department when fluid on the lungs was confirmed. Things could have turned out totally different. While in hospital for two days, I read about other trekkers not making it down from the EBC trek this season, one of them dying in the same week I was there.

A month later I’m still processing the experience and remain in awe at the beauty of the world’s highest mountain as well as the Sherpas and locals who often risk their lives in order to meet the expectations of international visitors.