‘It’s a ticking time bomb’: Fears still hang over Boeing’s fleet of 737 MAX planes after two fatal crashes

New alarms have been raised about a model of Boeing plane that’s increasingly common in Australia, with an expert calling it a “ticking time bomb”.

Plane manufacturing giant Boeing knew about a technical defect in its 737 MAX series before one of the aircraft crashed in 2019, new evidence suggests.

Five years after that doomed flight, the unsettling revelations keep coming – and at a time when one of Australia’s two major airlines, Virgin Australia, has ordered dozens of 737 MAX aircraft for its fleet.

Lion Air Flight 610 went down off the coast of Indonesia in October of 2018, followed mere months later, in March, by Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. Combined, the two incidents killed a total of 346 people.

Since then, Boeing has paid billions of dollars in settlements related to the twin disasters, though it has never faced criminal prosecution.

Boeing has already delivered seven of the planes to Virgin Australia, with 31 more scheduled to arrive by 2027.

An inquiry conducted by the United States Congress in 2020 identified “a disturbing pattern of technical miscalculations and troubling management misjudgements” at the company,

“The Max crashes were not the result of a singular failure, technical mistake, or mismanaged event,” the congressional report concluded.

“They were the horrific culmination of a series of faulty technical assumptions by Boeing’s engineers, a lack of transparency on the part of Boeing’s management, and grossly insufficient oversight by the Federal Aviation Authority (America’s aviation regulator).”

‘It’s unbelievable’: New evidence emerges

An investigation by Channel 7’s Spotlight program has found evidence that Boeing knew of a serious technical defect in the 737 MAX before the Ethiopian Airlines flight perished.

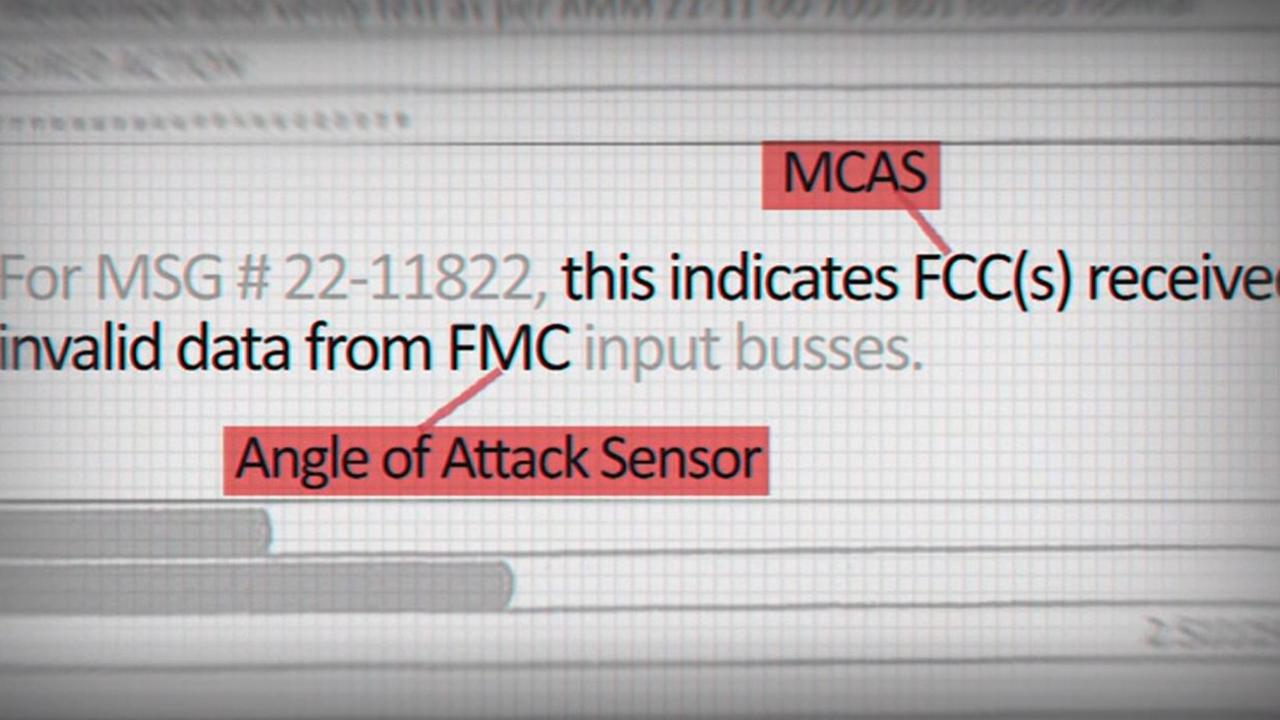

That crash happened due to a fault in the plane’s MCAS system, which is designed to automatically activate an aft flap to push the nose of the plane down if a sensor, located at the front of the aircraft, sends it information indicating the craft is about to stall.

In this case, the MCAS system was receiving false information from the sensor.

It believed the nose of the plane was pointed up at a dangerous angle of 75 degrees, when it was only at 15 degrees. The pilot was left to fight with his own craft’s malfunctioning system.

Compounding the problem, pilots had received insufficient training for operating the newly released 737 model – so as things went wrong, the pilot didn’t even know about the MCAS system that had broken down.

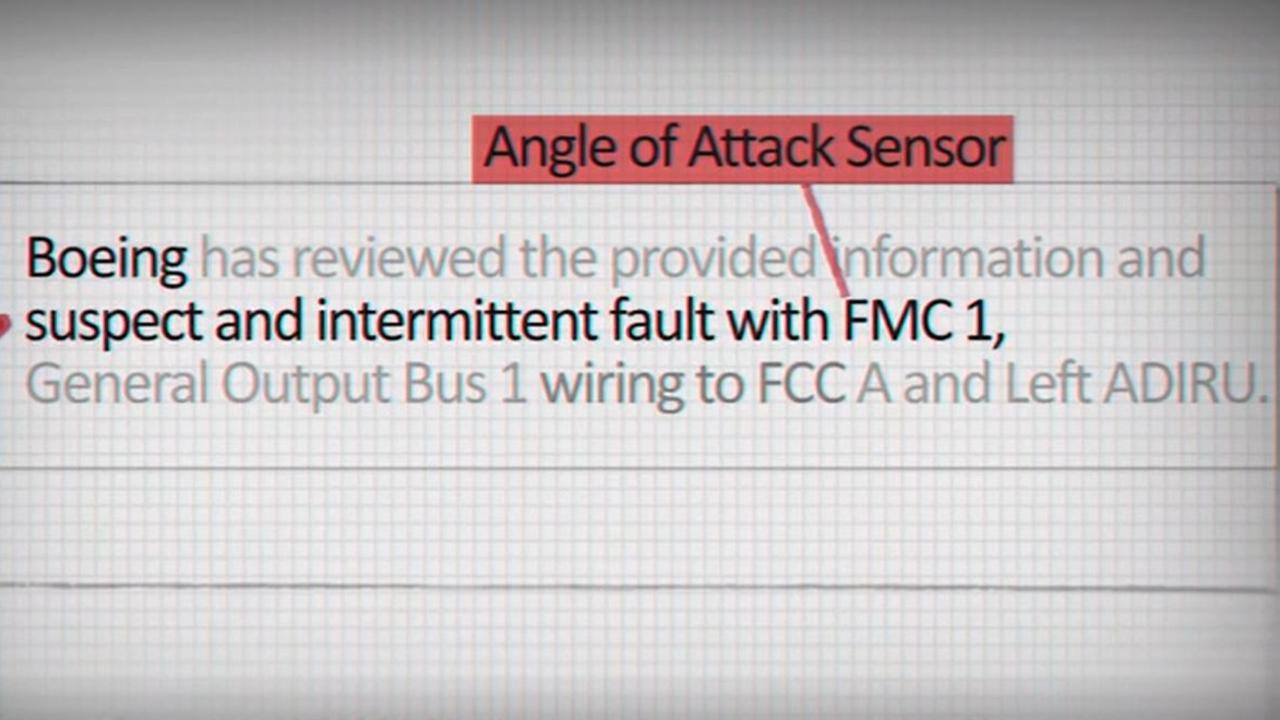

Correspondence from 2018, between Boeing and Ethiopian Airlines, was obtained by Spotlight.

It shows technicians working for airline reported the 737 MAX had encountered an issue involving “roll to right with autopilot engaged”.

After analysing the data, Boeing replied to the airline saying “we suspect it to be an intermittent electrical fault in the wiring”.

Specifically, a fault in the wiring of the sensor that provided data to the MCAS system.

That fault was suspected to be giving the MCAS computer “invalid” information.

This information was not provided to investigators after the plane crashed a few months later, when Boeing initially blamed pilot error.

“A few months later, they denied the plane had any manufacturing issues, ever. It’s stunning. It’s unbelievable,” Mr Pierson told Spotlight.

“When the Ethiopians were asking for help, Boeing not only said, ‘We suspect it to be electrical wiring.’ They started giving them directions on how to troubleshoot it.

“They said, ‘Check the pins for the connectors, check the connectors, do a continuity check, check the wiring, run the wiring’.

“Well, you can’t do that unless you pull up the boards, unless you remove a lot of stuff. You can’t get in and inspect that.

“It was an impossible suggestion for them to do. So they did minimal – basically, they did a couple things that Boeing had suggested and they said, ‘It must be good, because Boeing said that’s what we should do.’”

‘It scares me’: Former Boeing safety manager speaks out

Multiple whistleblowers told Spotlight they worried Boeing’s 737 MAX fleet may still be unsafe, despite the company’s insistence otherwise.

Interviewer Liam Bartlett asked Mr Pierson whether he would “voluntarily” fly on one of the planes now.

“No. There’s no way,” Mr Pierson responded.

“What I know, it scares me. And that’s why I’m agreeing to this interview, because I feel like the public needs to know.”

In 2017, demand from airlines for the 737 MAX started to outstrip the pace at which Boeing’s network of suppliers could provide the necessary parts. Mr Pierson said that caused chaos in the assembly process, with parts being added haphazardly instead of in a strict order.

“It started to crystallise in my mind that these are unnecessary risks. We need to shut down, we need to stop. This is madness,” he said.

Mr Pierson said he told people inside the company that, during his military service, programs would be shut down “for much less”. He was told, in response, that the military was “not a profit-making operation”.

When the Lion Air flight went down in 2018, two months after Mr Pierson had left Boeing, he wrote an “urgent” letter to the company’s board of directors, saying there could be a defect in the 737 MAX. Boeing had, again, blamed pilot error for the tragedy.

Then, in March, the Ethiopian Airlines flight crashed as well.

Joe Jacobson, an aerospace engineer, was an employee at Boeing for years and worked on the development of its 777 aircraft before he “switched sides”, so to speak, and joined America’s regulator, the Federal Aviation Administration, in 1995.

“The emphasis shifted almost overnight to shareholder value, stock price. Which to us engineers, we’re thinking, ‘What does that have to do with our job?’” he recounted.

“The shift was very apparent.”

During his time at the FAA, his area of responsibility included elements that concerned the steering of aircraft – including MCAS, and the manual trim system that failed in the second crash.

“Boeing had kind of made the case, or I guess led us to believe that the manual trim would always work, that it was almost 100 per cent effective,” Mr Jacobson told Spotlight.

“It turns out that was not even close.”

‘No accountability’: Victims’ families despair

Boeing was later charged, by the US Justice Department, with misleading the FAA over safety issues with the 737 MAX.

However the company’s legal team brokered a deal for a “deferred prosecution agreement”. Boeing paid a fine of about $US250 million, settlement costs running into the billions, and was placed on a good behaviour bond.

Multiple people who spoke to Spotlight slammed this “sweetheart” deal, and the Trump-appointed district attorney, Erin Nealy Cox, who’d been placed in charge of the Boeing prosecution. Ms Cox has since left the Justice Department and joined Boeing’s law firm, Kirkland & Ellis, in a high-paying job as a partner.

“No senior officer at Boeing was ever indicted or even investigated,” John Coffee, a professor of law at Columbia University, told the program.

Nor shall they be, it seems.

An unsettling Alaska Airlines incident in January, in which a 737 MAX’s emergency door blew off mid-flight, was then used by families of the Boeing crash victims to count as a violation of the company’s good behaviour bond, which would expose it once again to potential criminal prosecution.

Instead the Justice Department, now under the Biden administration, offered Boeing another, similar deal, with an additional requirement for it to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on its safety compliance programs.

Nadia Milleron, whose 24-year-old daughter Samya Stumo was among the victims of the Ethiopia Airlines crash, allowed Spotlight to film her during a video call with the Justice Department, in which it revealed its decision not to pursue criminal action.

She was visibly distressed and, at one point, shaking with anger.

“All the meetings start out with hope, and then the hope gets dashed,” Ms Millerson said.

“There is no accountability. And everything is proceeding with all the same problems that caused the first two crashes.”

“It’s nothing,” Ms Stumo’s father, Michael Stumo, said of the new fine.

“This case is about killing people, killing our daughter, killing 346 people. And after all this, it’s still presented to the court as some paper fraud against the FAA, full stop, with no further consequences.”

“I just think they’re evil. They don’t care about people’s lives. They’re paying for these lives from insurance, it’s not affecting their company at all,” said Ms Milleron.

‘Safety is fundamental’

Stuart Aggs, Virgin Australia’s chief operating office, told Spotlight that “safety is fundamental to the success of the aviation industry” and would always be the company’s “top priority”.

“Virgin Australia is one of over 80 airlines operating Boeing 737 MAX family aircraft globally,” Mr Aggs said.

“More than 1400 of these aircraft are in service around the world, carrying about 700,000 passengers on 5500 flights every day.

“Over the past 50 years, a journey of continuous improvement has made commercial aviation the world’s safest form of transportation.

“Virgin Australia retains full confidence in Boeing’s commitment to this journey.”

In a statement of its own, Boeing insisted it remained “confident” in “the safety and durability” of its aircraft.

“We also encourage and empower our employees to raise any concern, and we review each rigorously to ensure safety. We are focused on fostering a safety culture based on transparency and accountability.

“With safety and quality at the forefront, we are improving our production system to ensure we can reliably deliver and meet customer commitments.”

Boeing said its 787 Dreamliner had “safely transported more than 919 million passengers” since its introduction in 2011, and the 737 MAX had clocked “more than 10.2 million flight hours” since it entered service in 2017.

“Today, more than 80 airlines are operating more than 1500 737 MAX airplanes, with over 5500 safe flights daily,” the company said.

Meanwhile Australia’s aviation regulator, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA), said it was “satisfied that all Boeing aircraft meet all of Australia’s safety requirements”.

“CASA works with international partners to review any emerging safety issues. We will always act if required to ensure the safety of passengers,” it said.

CASA declined to provide an official to be interviewed on camera, and stressed the FAA’s responsibility for regulating the manufacturing of planes in the US.

Mr Pierson does not share the regulator’s confidence, nor Virgin Australia’s.

“They want to trust Boeing, because they’ve been able to trust them in the past. But they’ve got their head in the sand if they think these planes aren’t coming with problems,” Mr Pierson said of the airlines still using the planes.

He pointed to the Alaska QAirlines incident.

“They inspected other Alaska Airlines plans and found similar problems. Missing things, things not done right. And this is the thing about an assembly line: if you make a mistake, odds are you’re going to make them on other things.

“They keep failing, and nobody’s fixing it. It’s just a ticking time bomb.”