Buffalo Central Terminal: the huge ghost station in the heart of a city coming back to life

A railway station twice as big as Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station sits abandoned with the lights off. So we went inside.

Imagine a railway station as big as Melbourne’s bustling Flinders Street Station.

Now double it in size and add a bit.

Then empty it of all its passengers and turn the lights off.

Oh, and leave it stranded out in the middle of suburbia where it’s brooding bulk and eerie silence makes it seem utterly out of scale with the modest homes around it.

What you have is the grandiose but long shuttered main station of the city of Buffalo, in New York State, near the Canadian border.

Spread out among 61 hectares with a hefty brick skyscraper as its centrepiece, Buffalo Central Terminal has been called a “mega structure”. But it shouldn’t be here. Really, it should never have been built at all.

If more people knew about it, it’d probably be a famously forlorn landmark. But tourists have had a habit of bypassing Buffalo on the way to the flashier Niagara Falls just 20 minutes away. Indeed, for much of the last half century even the locals were keen to leave Buffalo.

But the Central Terminal is slowly coming back to life.

As is the city around it. Back from the post industrial brink, it’s now tempting tourists with quirky hotels, restaurants, galleries and its industrial relics are being repurposed.

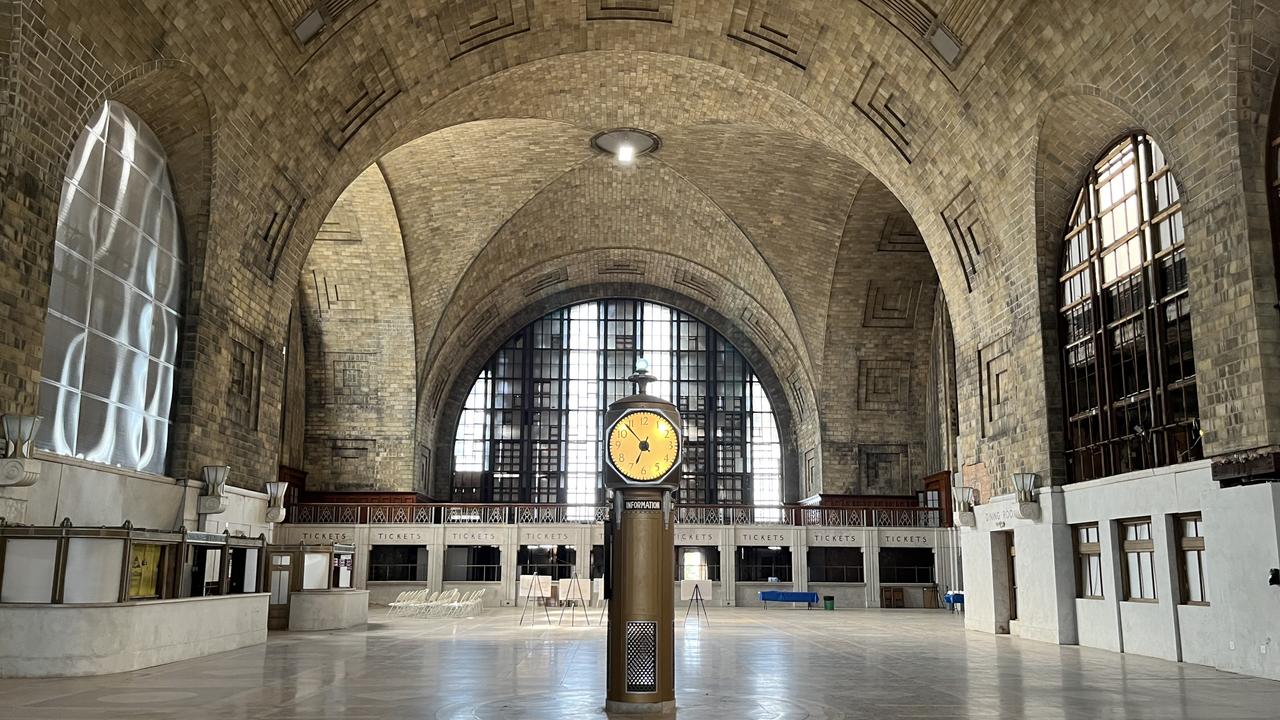

News.com.au got a rare look inside the cavernous concourse of this abandoned art deco transport masterpiece.

“I see people walk in, and you hear ‘oh my god’ and I know its first timers,” says Marty Slawiak, looking up at the intimidatingly massive six storey high arched ceiling of the former station’s hall.

Mr Slawiak’s father used to work here and for 18 years he’s been part of the team tending to the desolate terminus now full of memories and, some say, even a ghost.

It was constructed by the New York Central Railroad, which also built perhaps the world’s most famous railway station – New York’s Grand Central. Buffalo’s version is a third larger and almost as grand.

“Once this station was bustling. Buffalo was the sixth largest city in the country. Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin all came through here,” said Mr Slawiak.

“This terminal is a connection to our industrial heritage. But it reflects Buffalo’s economic decline and disinvestment.

“This is the story of our city right here.”

It opened in 1929, months before the Great Depression and just as Americans were embracing cars and shunning trains. By 1956 it was up for sale. It hasn’t seen a single passenger since 1979.

So sturdy, it’s thought only the huge cost to pull it down and it’s out of the way location saved it from demolition. It was cheaper to leave silently in situ.

The only noise now is the somewhat ominous banging of a loose window frame in the wind.

Terminal’s tragic heyday

The terminal was meant to be the centrepiece of a new downtown. Buffalo was growing rich as a cargo hub advantageously located by the Great Lakes and Erie Canal.

Hydro-electric power generated from Niagara Falls spurred an industrial boom which gave Buffalo the nickname “the city of light”.

As its population grew it acquired the trappings of a big city – a philharmonic orchestra, towering city offices, the Buffalo Bills football team.

“The thinking was Buffalo would reach a million people so we’ll build this grand station to accommodate them,” said Mr Slawiak.

“Passengers were made to feel like kings and queens here”.

Bags checked in, they could drop in on the station’s tailor, jewellers and barbers or feast in the dining room. Perhaps on the city’s most famous culinary creation – juicy, spicy Buffalo wings.

But, at the city’s peak in 1950, the population had only reached 600,000. Today Buffalo has barely half that.

Roads took over from waterways and the opening of the St Lawrence Seaway in 1957 saw Buffalo’s port bypassed altogether.

The city atrophied.

Central Terminal was only really busy for a brief but tragic period in the 1940s.

“The jewellers sold more $10 engagement rings than anything else when the men were going to war,” said Mr Slawiak.

Some of those newly engaged men who left by train would never return for their marriages.

Ghost of the man and his dog

After it closed, the terminal went through many hands including a builder called Anthony Fedele who, with just his dog for company, made it his home before he died.

With its stillness and dark corners, it lends itself to ghost hunts.

“On one they had all their meters and they said ‘Do you know Marty?’” said Mr Slawiak.

“And boom, all the lights and the meters go off,

“’Do you know he volunteers here?’ they asked, and everything spiked again.’”

Mr Slawiak believes it to be Mr Fedele’s spirit, keeping an eye on his building.

But he’s not worried by it: “I’ve come here at 3am to check on the place and I always feel at home.”

Upstate New York’s Brooklyn

Now owned by the Central Terminal Restoration Corporation, a $440 million plan aims to breathe life back into what it calls a “living landmark”.

Already $100m has been raised. $7m of that has been spent to shore up the building. Now it stands prouder, cleaner, free of rubbish, it’s iconic clock is once again lit at night.

Spruced up, ideas for its reuse include office space, exhibition and screening rooms, housing and even film and TV studio space.

Monumental grain silos now art works

“Buffalo had a reputation,” local Richard Smith III, sporting his trademark cowboy hat, tells news.com.au.

“We lost our industry, then we lost our people.

“But in the last few years something has changed. Suddenly this is the coolest place to be.”

It’s not just the reborn railway station – the Buffalo AKG contemporary art museum will reopen in May after a $300 million refurbishment.

Arty and alternative, residents say Buffalo is to upstate New York what Brooklyn is to New York City.

“You can go on a kayak on the river between these stark industrial landscapes and there’s nothing like it in the world,” said Mr Smith who is the CEO of Buffalo firm Ridigized Metal.

He told news.com.au he took on his family’s metal business after discovering, “there ain’t no money in poetry”.

He’s also the custodian of another of the city’s relics, right by the revitalised waterfront. In 2006, he bought a job lot of huge grain silos which had been left to rust.

“I didn’t know what the hell I was going to do with them then. Here I am years later, still not knowing what the hell I’m going to do with them – but having a blast.”

He’s being somewhat modest. Collectively they’re now known as “Silo City”. Some are being turned into apartments, others are art installations. Projections flood light the side of the giant white hulks while equally huge pieces fill the interior. At times, concerts reverberate inside. Four times a year poets take over as part of the Silo City Reading Series.

In the shadow of the silos, next to long overgrown railway tracks, is Mr Smith’s bar and live music venue Duende.

It’s clad in on-site salvaged materials – wood and distressed metal; poetry is emblazoned on the walls. Punters can sup a beer while gazing at the industrial past right outside.

Mr Smith cites Larkinville as another example of Buffalo’s renaissance. What was once a “wasteland” of old warehouses, is now flats and co working spaces. Restaurants have opened and events take over the nearby square.

Larkinville’s Swan Street Diner is housed in an authentic 1937 dining car. Every day it serves spicy breakfast tacos, Buffalo chicken wraps and stuffed banana peppers with cheese curds and siracha.

Near the AKG art gallery, a former mental asylum will soon reopen as the boutique Richardson Hotel.

Not that Buffalo doesn’t already have several of them.

The historic Mansion on Delaware Ave is a former 18th century home which was – you guessed it – once abandoned.

Its 28 rooms are cosy and warm while its living room is perfect for kicking back with a glass of red.

The positive change to Buffalo even shocks locals.

“We lost our young people and now young people want to be here,” said Mr Smith.

“We’ve got the Philharmonic, we got the Bulls, we’ve got a whole bunch of things that a 260,000 person city would never have had today.”

Formidable but almost forgotten landmarks like the Central Terminal and silos, homes and an asylum, are now the cornerstones of a city’s revival.

The reporter stayed in Buffalo courtesy of Visit Buffalo Niagara.