The Sydney Harbour Bridge doppelganger hiding in New York

Almost hidden in New York is a landmark that stops Australians in their tracks – but that’s not the only startling thing about this iconic structure.

New York City is not short of famous bridges, none more so than the crossing that’s appeared in a thousand movies: the Brooklyn Bridge.

But if an Aussie were to venture just a little off the tourist track they would see a bridge that might baffle them.

In the Astoria neighbourhood of Queens, the skyscrapers of Manhattan still visible in the distance, is what appears to be the Sydney Harbour Bridge. But just, weirdly, on the other side of the world.

What, a tourist may ask, is it doing here?

To be fair, many bridges are of standard designs (crossings similar to Sydney’s Anzac Bridge are numerous) but none look as much of a carbon copy of the Harbour City’s landmark as New York’s evocatively named Hell Gate Bridge.

Almost every inch, from its gracefully curving arch to its four stone pylons, is pure Australiana.

Bridge ‘in the background’

Aside from its (very different) location, (slightly smaller) size and (terrible) paint job, structurally there is only one alteration – and if you spot it you should win a prize.

“The Hell Gate Bridge performs a fabulous job but it’s sort of in the background,” Bob Singleton of the Greater Astoria Historical Society told news.com.au.

“New York is a very romantic place – they talk about the Brooklyn Bridge.

“But people don’t write songs about railroad bridges. Yet the Hell Gate Bridge, on a number of levels, is one of the most significant bridges in New York City.”

Yet this secret Sydney Harbour Bridge is not all it may seem. The Hell Gate Bridge was here first.

And it’s that fact that stops some Aussies in their tracks: it’s the coathanger that’s the real copycat.

“I didn’t realise that the Sydney Harbour Bridge is based on this bridge,” said one commenter on social media about the Hell Gate.

New York’s crossing was completed in 1916, more than a decade before the opening in 1932 of Sydney’s bridge.

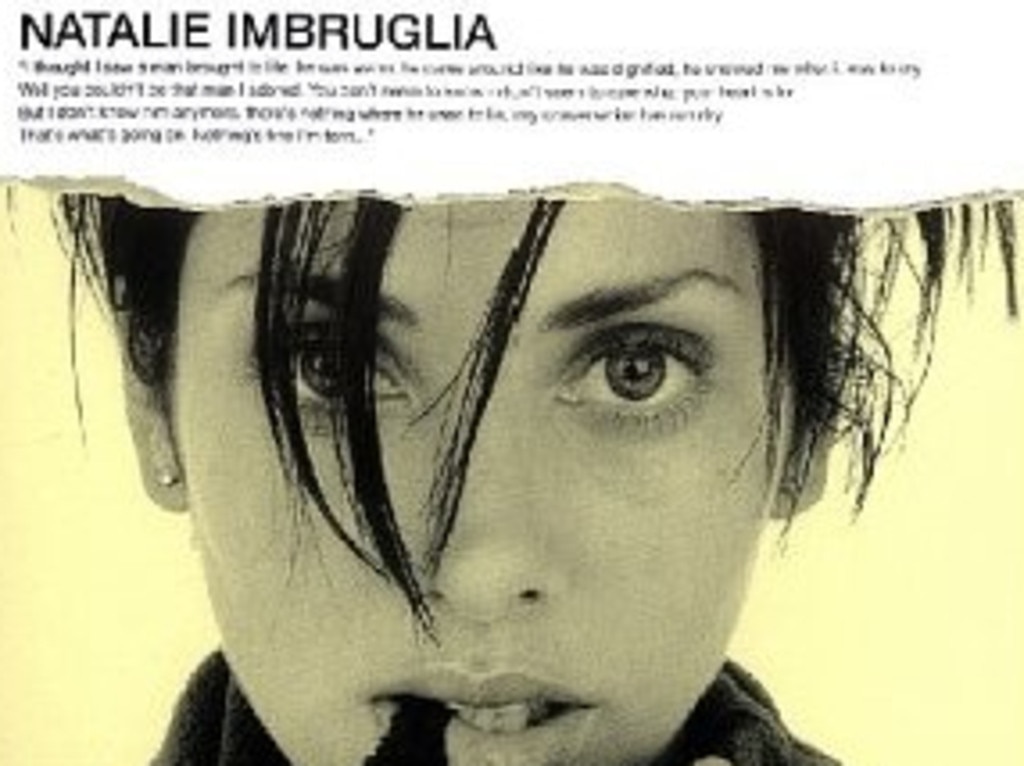

Like Natalie Imbruglia’s chart topping cover of Lis Sørensen’s Danish hit Torn, the remake has become more celebrated than the original.

But while its fame is more limited, it’s role remains vital.

“This bridge is more than just a bridge. It’s a statement,” said Mr Singleton.

“From railroad, to industry and to business – this bridge is the American spirit”.

New York’s big problem

At the end of the 19th century, New York already was a hub of US, even global, trade. Much of that trade was based on New York’s sea ports with the goods sent up and down the Hudson River, Erie Canal and the Great Lakes to the continent’s interior.

“The problem was that the rest of the country got into railroads but New York was stuck with barges,” Mr Singleton said.

“It was getting to the point New York was going to lose its position.”

New York’s geography, of multiple rivers, islands, inlets and escapements didn’t help.

An extraordinary structure was needed to link the Pennsylvania Railroad with points north. And Austrian/Czech engineer Gustav Lindenthal delivered just that.

Hell Channel

If you combine the enormous approach viaducts, which lift the train line through the suburbs, the bridge complex is a full 5.2km in length.

But the section that feels so familiar to Australians is a fraction of that. It’s 310 meters long (compared to Sydney’s 500 meters) as it crosses an unglamorous stretch of the East River called the Hell Gate.

This fearsome name is a corruption of the Dutch name Hellegat. It harks back to the then Dutch colony of New Amsterdam.

It meant “Hell Channel,” an apt name due to the treacherous conditions for a waterway that leads to the Atlantic from both ends and which saw many a ship succumb, battered on the rocks on either shore.

Begun in 1912, the through arch bridge would take just four and half years to complete.

“This was before computers, but when the two ends of the bridge met over the river they were just half an inch out,” said Mr Singleton.

The single structural difference

Mr Lindenthal had designed four decorative pylons, two at either end to gracefully frame the bridge.

But they had no role in supporting the bridge which was stabilised by its steel arch alone. Concerned that the public might believe the pylons were vital to hold up the bridge, Mr Lindenthal added unnecessary girders to physically connect the arch and tower.

Sydney, too, added pylons to its bridge to make it seem sturdier. But if you look closely at the Harbour Bridge you’ll see there’s a gap in the steelwork between the arch and the towers. It’s one of the few differences in this intercontinental doppelganger.

Nazi plan to fell bridge

The Hell Gate Bridge immediately became essential to New York’s livelihood transporting people and goods.

So essential was it that during World War II the Nazis planned for its destruction.

But excepting a nefarious plot to bring it down, the bridge could stay up for a thousand years, some estimate due to its sheer bulk.

That’s hundreds of years longer than road bridges that need their surfaces to be maintained.

Dodgy paint job

The same can’t be said for its paint job.

It’s original dull hue, applied in 1916, did the job for 60 years before fading.

In the early 1990s, the current owner Amtrak – the US’ intercity rail operator – repainted the bridge in a unique red colour – in an attempt to capitalise on its hellish name.

But the devil red pigment began to fade even before the bridge had been fully repainted.

“There was nothing wrong with the paint job,” Greg Campbell of George Campbell Painting, which applied the paint, told the New York Times in 2012.

“Truth is that the paint colour faded. The paint manufacturer was the cause of the problem.”

The paint firm eventually conceded it had changed the company that made the pigment prior to supplying the paint.

To this day the bridge is a messy, blotchy red and pink.

But unsightly as it is, it poses no risk. And repainting the huge structure won’t be cheap. It’s a cost no one wants to spend for a cosmetic touch up.

The Hell Gate Bridge’s achievements were not lost on celebrated Australian engineer John Bradfield who was quite open that his bridge across Sydney Harbour was inspired by the pioneering New York structure. But he wanted it to be bigger and better.

That and the Sydney Harbour Bridge’s far more central and spectacular position has brought it the worldwide acclaim the Hell Gate Bridge found more elusive.

The newer bridge in Australia stole the thunder from its inspiration in America.

Today, the Hell Gate Bridge continues to be a vital part of the transport network in the US. Every day multiple Amtrak trains clatter across it carrying thousands of passengers alongside numerous freight trains.

“I always say that if there’s any other country most like America, it’s Australia,” said Mr Singleton.

“So I can certainly understand Australians looking at this bridge, building something similar to this bridge, and being really interested about this bridge, because it exemplifies that kind of spirit that both our cultures, both our countries, have which is ‘we can do anything’”.