Queen Victoria Building: Behind Sydney’s most mysterious door

Tens of thousands of people pass it every day, but where does it go? It’s one of many secrets and sleights of hand at this famous city landmark.

There’s something not quite right about the door to room 417. At first glance it looks like your standard door – solid wood, shiny door knob.

But who puts a door halfway up a staircase? One that hovers almost a metre from the ground, meaning you’d have to leap into it. And why does a metal banister cut straight across it, barring entry?

It’s not the only odd door in Sydney’s landmark Queen Victoria Building. The door to room 432 is similarly slap bang in the centre of a staircase and too small for your average adult. Next to that is an ex-door; now bricked up and painted over – just a frame remains.

The building’s guest experience manager and tour guide John Burdon tells news.com.au they’re easy to miss as you rush through the passageways of QVB, one of the city’s busiest shopping hubs and thoroughfares.

But from the mystery of the doors, to the suspiciously spick and span historic interior, and the famous statue of Queen Victoria that stands outside, nothing is quite what it seems at the QVB. Secrets, stories and visual sleights of hand are at every turn.

“There are hidden spaces everywhere around this building,” Mr Burdon says.

There’s even the odd spirit to be found, floating around the high-end fashion stores.

Last week the QVB marked 122 years. Now managed by Vicinity Centres, which also runs Melbourne’s Chadstone and Emporium and Sydney’s Chatswood Chase and The Strand Arcade, the company hopes to restart behind-the-scenes tours shortly.

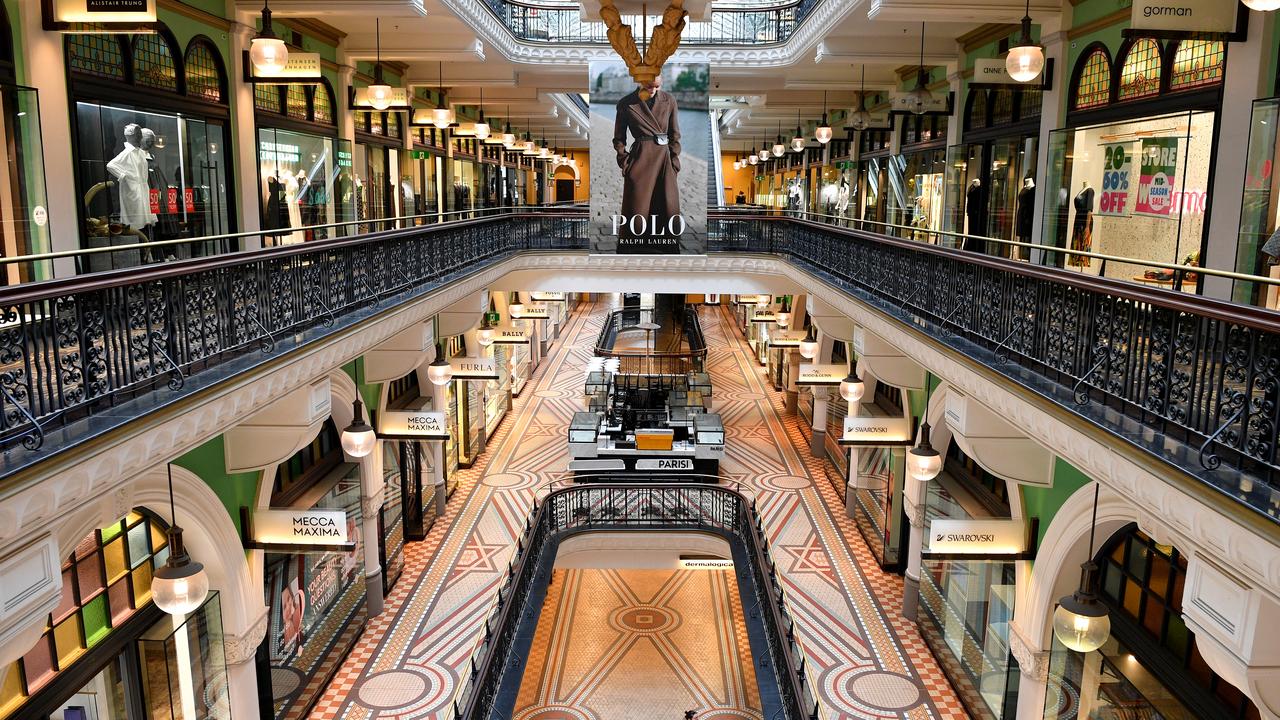

“Now it’s one of the most beautiful shopping centres in the world,” Mr Burdon says.

“But the QVB is a testament to the attitude of each generation. The attitude of, we need a new building, now we hate it, now let’s tear it down and now we need to save it.”

A FINANCIAL DUD

The building first opened its doors on July 21, 1898, partly to house the street market that had crowded around the also relatively new Sydney Town Hall.

The QVB was extravagant; it featured marble, stained glass and no fewer than 20 copper plated domes as well as the huge centrepiece dome. It was also hideously expensive, with Mr Burdon estimating it cost $865 million in today’s money.

“From day one, it started to fall into economic decline,” he says.

“The grandeur and foresight were there but because of the size of the tenancies and rent they couldn’t fill the building.”

OBLITERATED THE INTERIOR

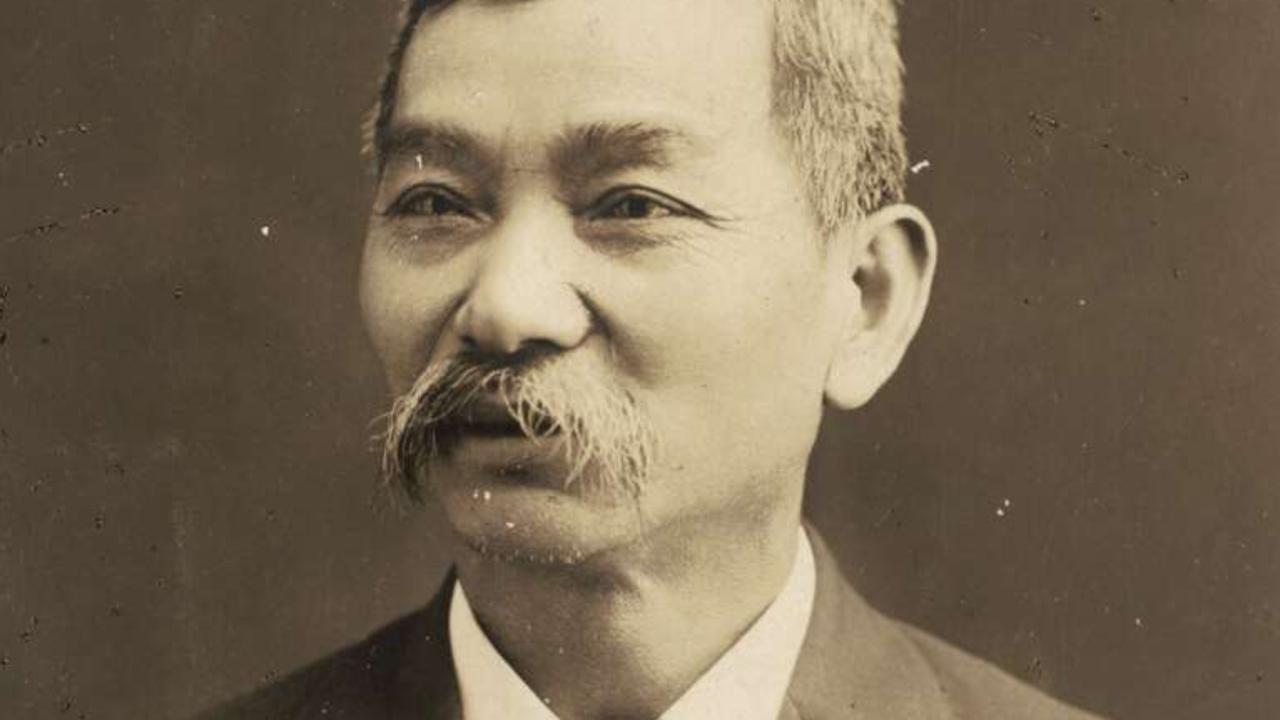

Thank goodness then for Mei Quong Tart. Well known around town, this Chinese trader was always immaculately dressed in a suit and bowler hat and, notably, spoke English with a Scottish accent.

He opened a branch of his tea rooms at the QVB. A plush staircase led to the “elite dining hall”. Here, women could often be found deep in conversation. This was no idle chit chat; they were plotting revolution. The tea room was a meeting place for Sydney’s suffragettes who were successful, in 1902, in their campaign for women to have the vote.

In 1904, Mr Quong Tart was viciously beaten while he totted up the day’s takings. The rumour was it was a racist attack. He died a year later and his tea rooms closed.

Losing such a major tenant was a body blow for the QVB. In 1917 the council, desperate to fill the huge building, turned it into offices.

“They pretty much obliterated the entire interior. It was all too opulent, so they concreted over the tiling and it was carpeted, spilt-levelled and subdivided,” Mr Burdon says.

RELATED: The gruesome secrets lying beneath Sydney’s Central station

The building’s ground floor exterior was later also heavily remodelled to erase the 1898 decorative Romanesque design.

“By the 1950s, the QVB was seen as a relic of the past. It was this giant monster in the centre of the city that was decrepit and derelict.”

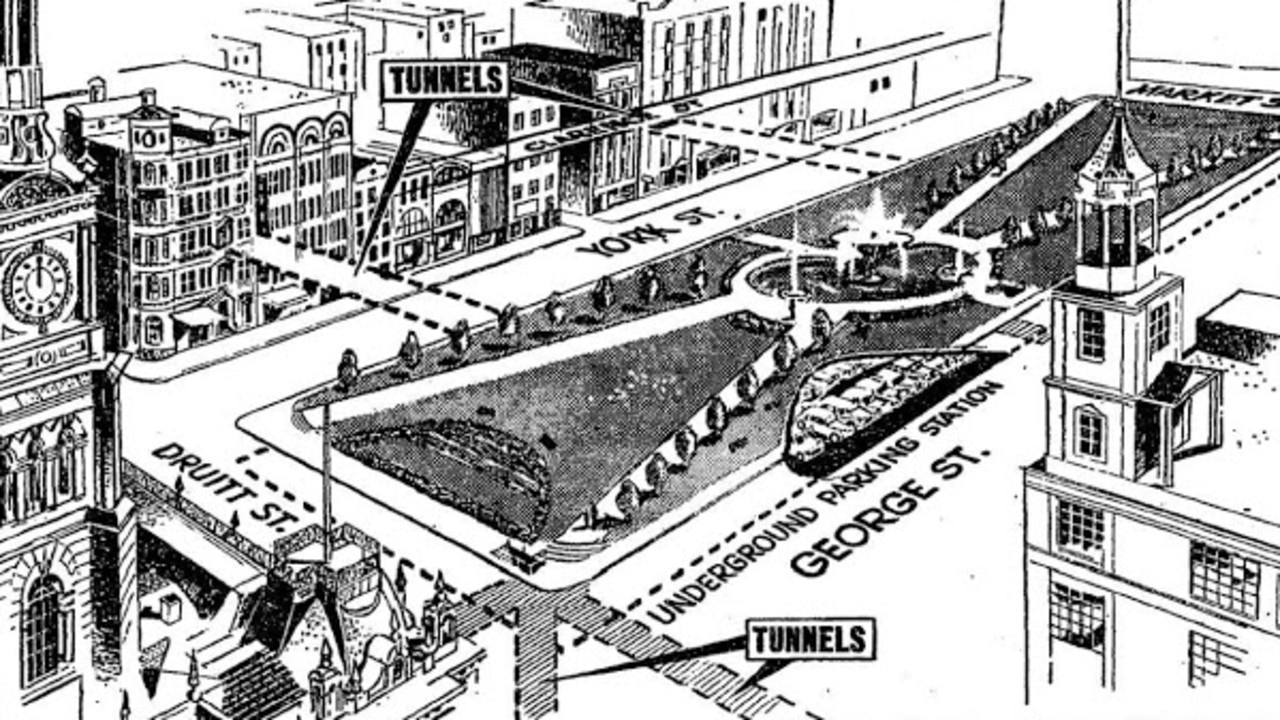

For decades it was under constant threat of demolition to be replaced by a car park and civic square. Political dithering and a growing appreciation for conservation meant that never happened.

QVB REBORN, BUT LITTLE LEFT TO RESTORE

In the 1980s, Malaysian developer Yap Lim Sen proposed returning the QVB to its former glory as an up-market shopping centre.

But by then not that much remained of the QVB. The only original features were the exterior – and even then, only from the first floor up – some stained glass in the dome and windows, a few tiles, metal work and the men’s urinals.

Almost all the period features people marvel at today, from the balustrades to the clocks, are a trick of the eye, dating from around the mid-1980s.

“They had to recreate what they could from old photos. They destroyed the ground floor, all of it is refurbished, none is original,” Mr Burdon says.

RELATED: Eerie underground world right beneath Sydney CBD

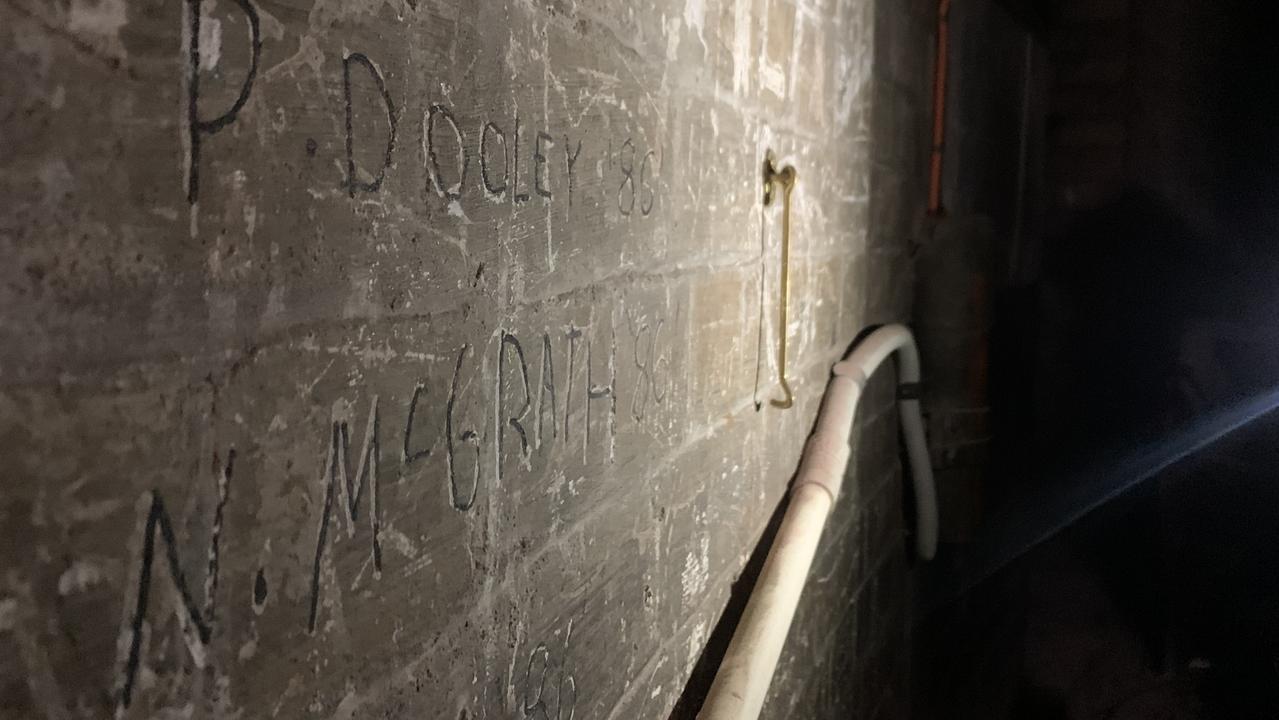

Scratched into the walls in dark corners of the building are the names of the workers who recreated the QVB.

Even Queen Victoria is a new addition. The developers wanted a statue of the former monarch to grace the entrance.

Ireland, which in 1922 threw off the British rule, had one spare.

“She used to sit outside the Irish parliament in Dublin. They didn’t want her there, so then she was outside a museum, then a school, finally they found her in a farm shed before she was shipped here”.

QVB’S MYSTERY DOORS

And what of those mysterious doors peppered around the building?

“It would be great if they were all secret passageways, but we’re not 100 per cent sure what they were all for. Some may have been serving areas for the dining rooms.”

That their original use is lost is also due to the many alterations to the building.

But room 417 had a special use.

“There were horse and carriage lifts in the building. The horse would step onto a flat platform and a lever could be pulled to lower the hydraulic lift down to the basement markets.”

They were close to the passenger lifts (which have also been restored), but were hidden away behind a wall so shoppers couldn’t see the horses descending.

“These doors were access points in case the lift broke down so someone could clamber in, get to hydraulics, and fix it.”

Today, the various doors lead to small rooms, some for electronics and airconditioning – all the things you need in a modern shopping centre. Some lead nowhere, the rooms behind subsumed into shops, all access denied.

Look closely and you may spy a circular metal staircase. Rickety now it leads to the grand dome. However, it had a secret use to provide soldiers with access to the building’s highest point in wartime. Before skyscrapers hemmed the QVB in, you could see across the harbour to check if the enemy approached.

That so little of the original 1898 QVB remained meant it was a struggle to get it protected.

It was only in 2010, more than a century after it opened, that officials were finally persuaded that it should be heritage listed. But more for its pivotal role in Sydney’s development than its actual fabric.

“It was created for the people of Sydney and it was saved by the people of Sydney who refused to see it turned into a car park,” Mr Burdon says.

“It’s the beating heart of the CBD and we have a duty to honour that.”

Aside from the sandstone and domes, and the odd tile and glass pane, there is another throwback to the QVB of old.

Mr Burdon says staff insist the ghost of Mr Quong Tart remains, not all that far from the door to room 417.

“He’s been seen on level two, in a three-piece suit and bowler hat. He waves at people and then disappears.”

benedict.brook@news.com.au | @BenedictBrook