The gruesome secrets lying beneath Sydney’s Central station

250,000 people stream through this iconic station every day, yet under their feet, just out of sight, is a grim reminder of Australia’s past.

It’s one of the single busiest locations in all of Australia. Every day an estimated quarter of a million people pass through Sydney’s Central Station.

But below the platforms, out of sight of the hubbub above, something has been lying silent for more than 100 years. Something that would make most people shudder.

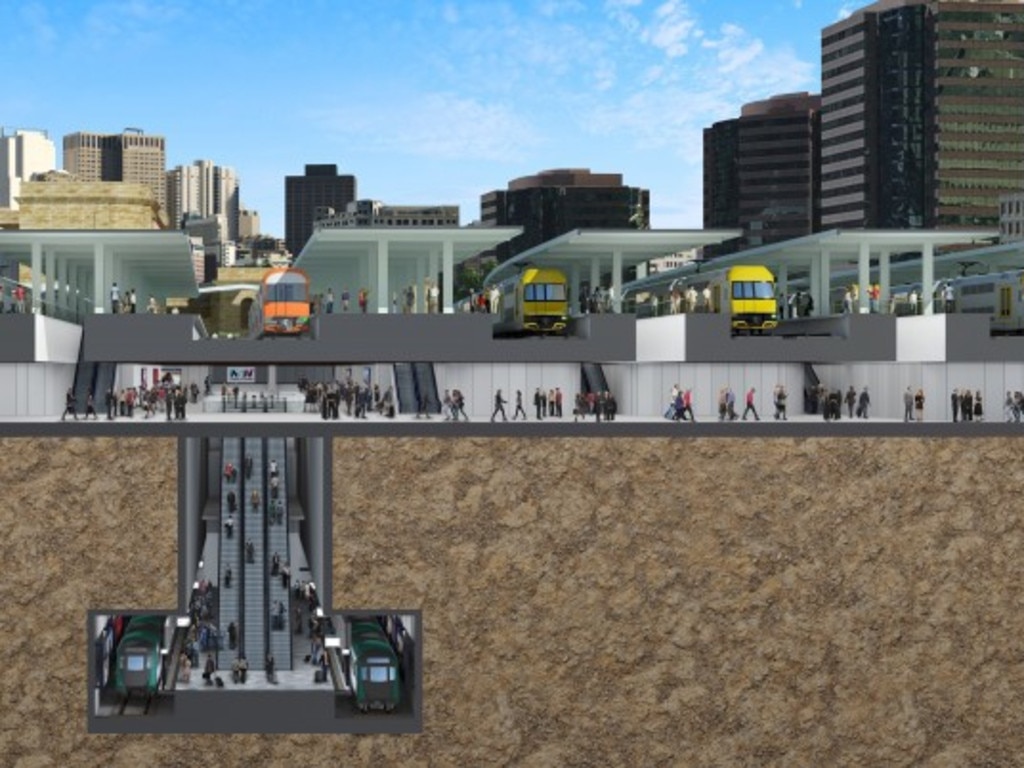

During the construction of the $12bn Sydney Metro rail line, that silence was disturbed.

Most commuters can’t have failed to notice the immense amount of building work at Central. Whole chunks of the station have been ripped out and replaced with a 220m wide cavern 30m deep to build a new underground station.

On the way down, the contractors started uncovering something unexpected. Buried in the thick mud and spoil were strange shaped blocks. Like a building, but far smaller.

“They’d been excavating around platform 13 and they had to stop digging,” Elise Edmonds, a curator at the State Library of New South Wales, told news.com.au.

“The archaeologists dug down and they found these 19th century structures, these little brick vaults, crypts.

“Then they started finding human remains.”

RELATED: The Sydney railway station designed for the dead

RELATED: Construction to begin next year on new concourse at Sydney’s Central Station

RELATED: Crowds pack new Sydney trams but say they’re too slow

Laing O’Rourke, the company that is building the Metro station at Central, estimates they have now uncovered as many as eight skeletons. They lie in the soil; the cheap wooden coffins that surrounded them have long since rotted away and many of the bones have dissolved to dust.

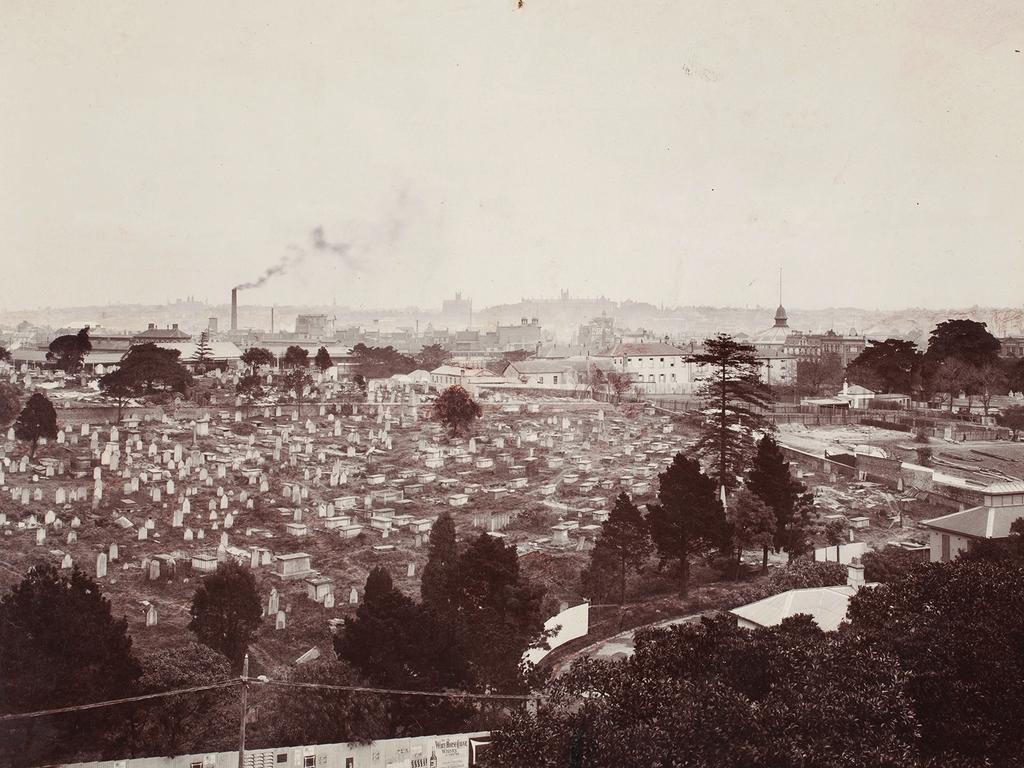

They shouldn’t be here at all. A massive cemetery that at its peak was the resting place of 30,000 souls was supposed to have been fully exhumed in 1900 to make way for Central Station.

The remains are ghostly reminders of the area’s grim past. Some railway staff swear you can still hear the eerie echoes of this vast station’s history in its more distant corners.

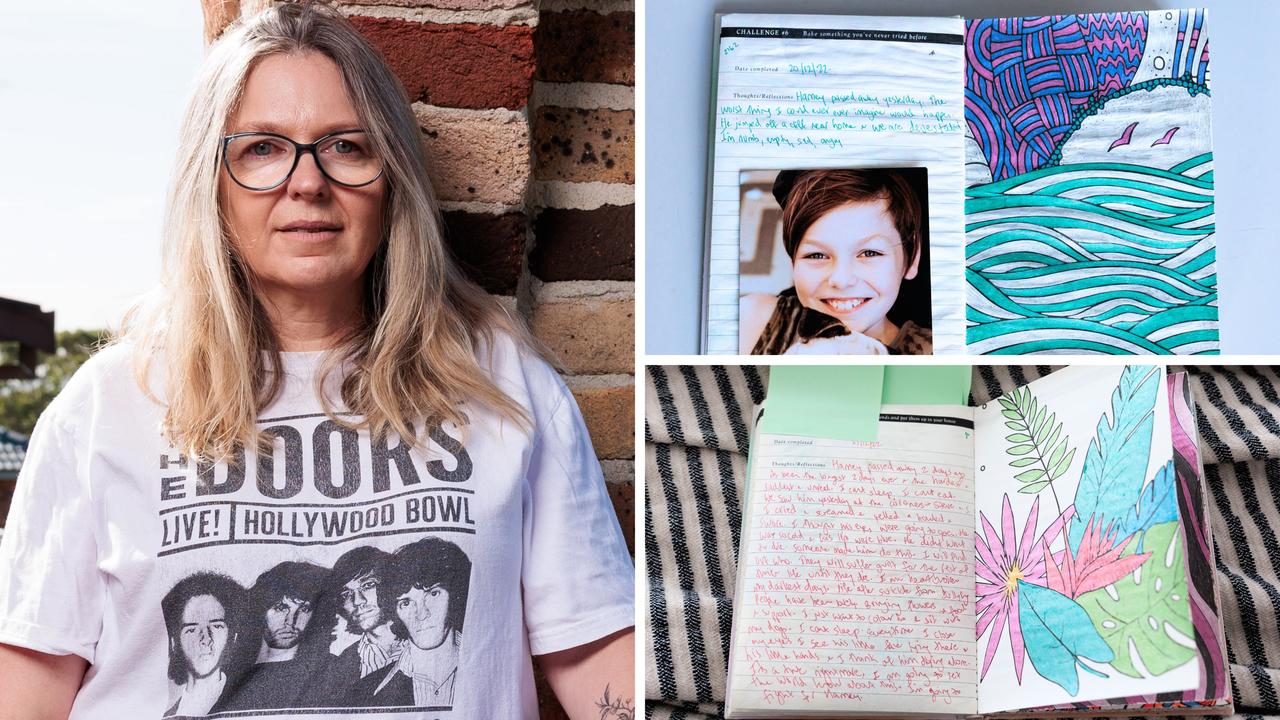

“When you’re in the zone of commuting, you wouldn’t think about it. But this frenetic, busy place, with so many thousands of people going through daily, used to be a sprawling, overgrown 19th century cemetery,” said Ms Edwards, who has curated the Dead Central exhibition at the NSW State Library which documents the history of the long lost Devonshire Street Cemetery.

Princes and paupers were buried within its walls, from street children who succumbed to disease to David Jones, the merchant whose business became the department store we know today.

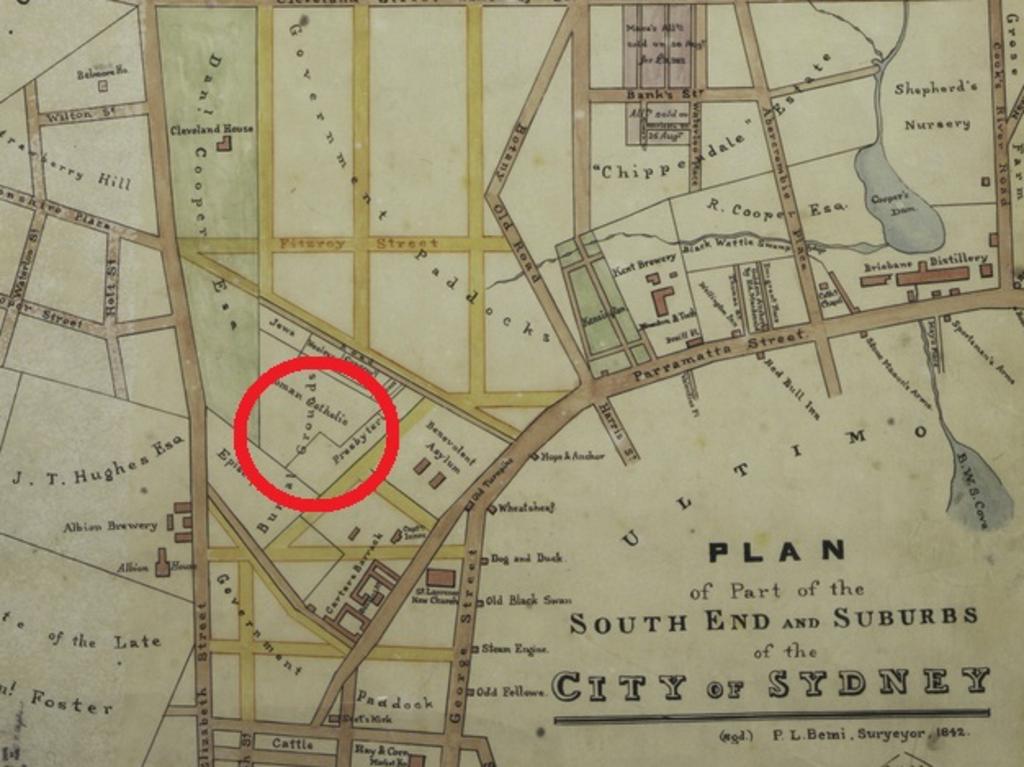

In 1820, Sydney was still in its infancy. Governor Macquarie ordered a cemetery be built on an undulating patch of land to the city’s south in what is now Surry Hills.

“At this point, the city was really just around George St. So the cemetery site was way out of town,” said Ms Edmonds.

And for good reason, because no one wanted a working graveyard on their doorstep.

It was neatly subdivided for different denominations and religions. Areas reserved for Anglicans, Catholics, Quakers, Presbyterians and Jews.

Devonshire St was built to the south of the cemetery and one of the first Sydney terminal railway stations beyond that.

“It quickly became overcrowded. So much so that within 20 years of opening, there were already complaints to the city council,” said Ms Edwards.

“We have a letter which talks about the noxious gases and bad smells that were emanating from the cemetery.”

This was likely because far more bodies were being interred there than intended and regulations about appropriate burials were being ignored.

INSALUBRIOUS

It wasn’t just the dead that occupied Devonshire St; the living were doing a thriving trade within its walls and between its headstones.

“It was very insalubrious; it was the dodgy end of town near the old station and all sorts of ghastly things were happening.

“I don’t know about body snatching but there were many escapades taking place. Prostitution was also happening at the graveyard.”

Ms Edwards said what caught her eye about the cemetery was the poetic and sometimes frank language used to memorialise the past.

William Liver, who died 1821, was “accidentally killed by a bullock cart”, one headstone claims.

The plinth of Samuel and Easter Bradley, who both died in 1822, claims they were “inhumanely murdered by their own servant”.

Then there’s Samuel Lepton, who died aged 27 in 1825. His headstone makes no bones: “the wicked Byron shot me”, it proclaims. “The awful summons soon must come when you must answer for my blood before thy maker and thy god. Byron, prepare to meet they doom.”

Aboriginal people were also being buried in Devonshire St but few records remain. One, however, was Cora Gooseberry an indigenous woman of the early settlement who was such an identity, she was called “Queen Gooseberry”.

Ms Gooseberry was never seen without her clay pipe and headscarf and would demonstrate her boomerang throwing skills down at the Harbour as well as taking people on tours of Aboriginal rock paintings.

She lay close to Supreme Court judges, members of the Fairfax clan and, working people and ex-convicts.

“There were people in their prime who fell of their horse, one woman died of a broken heart, so there’s all this tragedy in there.”

BODIES BURIED BENEATH PATHS

The graveyard became so full that it was officially closed by 1860. But, unofficially, bodies continued to find their way to Devonshire St, some even entombed beneath winding paths.

Before long the city grew up to the gates and spread around the graveyard’s perimeter. It was an oasis of calm but Devonshire St was thronged with trams carrying commuters streaming off trains from Parramatta further into the CBD.

The railway was the graveyard’s downfall. Its location meant it was blocking the railway’s progress further into Sydney CBD. In 1900, the Government ordered the bodies to be removed and the ground levelled for a tangle of railway tracks and platforms.

“If your relatives were buried, you had the choice of where you would like them to be moved. Some watched as the diggers put the remains into new wooden coffins,” said Ms Edwards.

Those charged with the grim task of interring the bodies had a few surprises. While many bodies were just bones others were surprisingly preserved.

One man, named Stevenson, was found still looking fancy in his suit. Another coffin contained just bones but on the feet were the most glorious Chinese slippers.

The next day, when the diggers returned, they found candles and incense placed all around the grave. A memorial from persons unknown.

It took just six years to clear the graves, level the ground, and build Central Station, the vast majority of which survives. The tombstones were entirely replaced by trains.

“It was remarkably quick. Just men and horses doing all that work,” said Ms Edwards.

Devonshire St, the boundary between the suburbs and the cemetery, became a busy tunnel beneath the tracks, a role it continues to play.

Just a few thousand of the bodies were claimed, many of those being reinterred at the new Rookwood cemetery in Lidcombe. Their final journey saw the coffin taken from the elaborate Mortuary station, still visible today, to the city’s west.

Unclaimed bodies were sent to a burial ground in Botany Bay. Despite the care taken, no one really knows how many people were buried. At some point the decision was made to stop digging even though other bodies might still be there, somewhere in the soil and sand.

GHOSTLY VOICES

Eerie echoes of the cemetery are said to remain. Two finished but never used platforms can be found deep underground on the station’s eastern side.

Ms Edwards said she never got a shiver down there but Sydney Trains’ employees had claimed to have heard strange noises in its trackless, dimly lit tunnels.

“Staff talk about how, when you’re on the disused platform, they have heard children’s voices.”

She isn’t convinced: “People love to tell a story. But there was a lot of children buried in the cemetery dying of all these awful diseases, epidemics and accidents.”

Ms Edwards said she is not surprised by the fascination for Devonshire St Cemetery.

“For white Australians, it was that time before Federation, the first time they were looking back at their history, the first and second fleecers.

And everyone goes through Central so it’s that familiar place that is fascinating because it’s so different to what it was.”

It’s likely the bones, uncovered recently, come from the southern portion of the cemetery which was for Catholic burials.

Soon, construction will begin digging on a different portion of the site. They expect more bones and vaults will make themselves known.

When people walk through the Devonshire St tunnel, stand on the platforms or wait for trains underground, is it possible they could be just metres from the remains of a long-lost soul forgotten about in Sydney’s old resting place?

“It’s possible,” said Ms Edwards, “yes, it’s possible”.

Dead Central is now on display at the State Library of NSW, Macquarie St, until May 2020.