‘I’m nervous’: Concerns double whammy of climate drivers could supercharge El Nino

El Nino is upon us, but lost in the announcements was the sting in the tail of the 2023 event that’s concerning weather watchers.

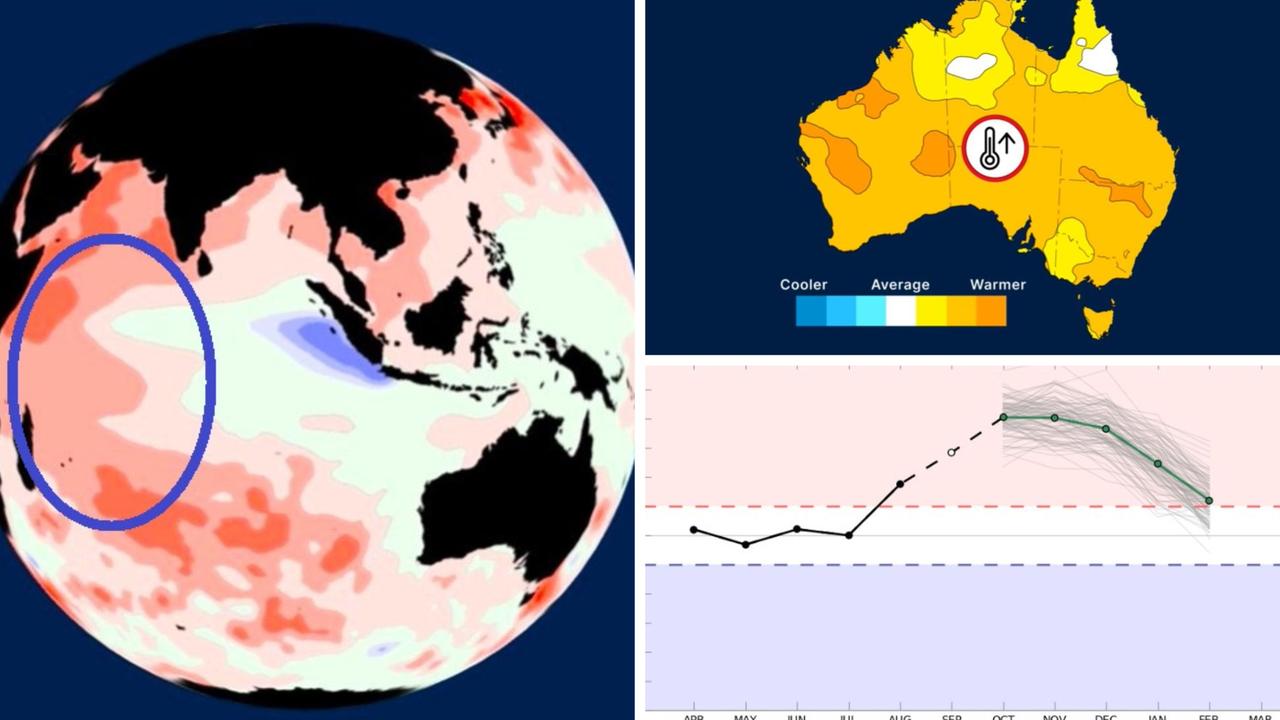

Anyone mildly abreast on the weather will know that last week the Bureau of Meteorology declared an El Nino was underway.

But somewhat lost in the flurry of El Nino announcements was another warning.

Meteorologists have flagged Australia’s “other” El Nino, a similar yet separate climate driver, is occurring simultaneously.

And this double whammy of climate woes could supercharge their overall effects.

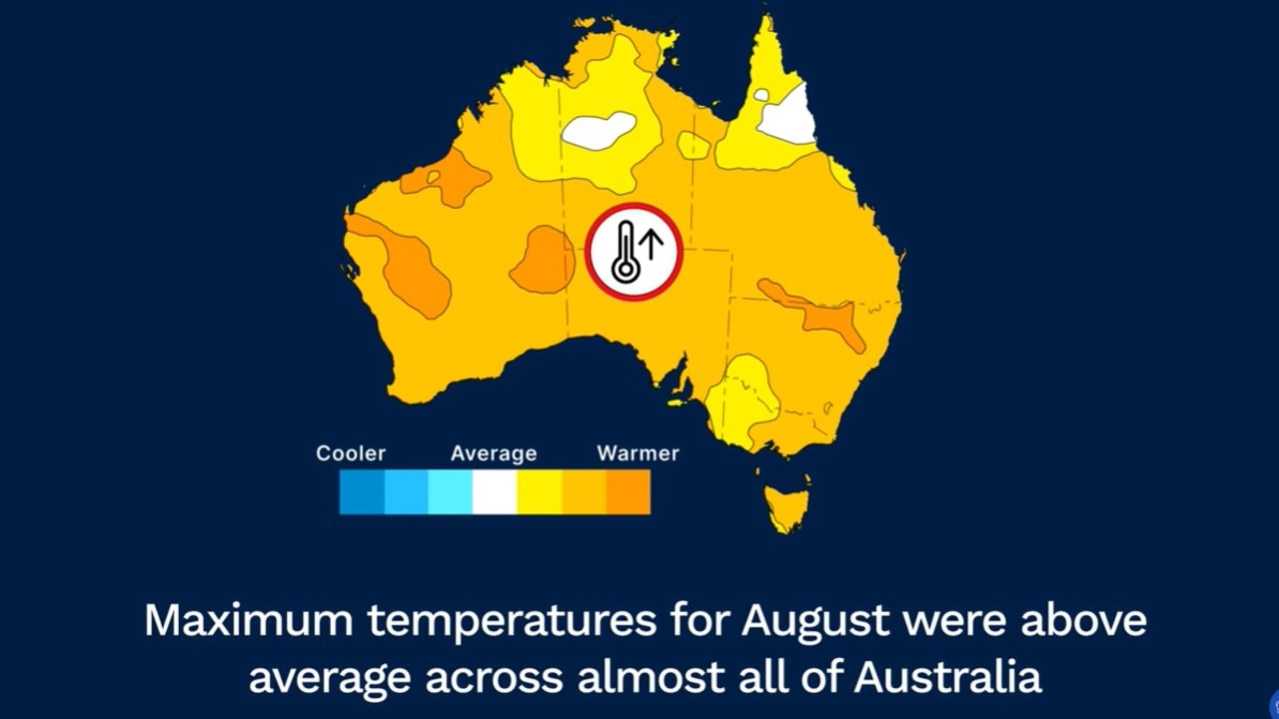

The recent run of unseasonably warm weather in the east, just weeks after winter ended, could be just the beginning.

Former commissioner of Fire and Rescue NSW Greg Mullins summed it up while talking to the BBC last week.

“Bushfires will be back in the headlines,” he said. “I’m nervous.”

A meteorologist has told news.com.au that 2023 could be “very dangerous” and while it was is unlikely to be as bad as 2019’s Black Summer, it might not be far off.

With El Nino at full pelt, eastern and southern Australia in particular can expect less rainfall and hotter days and nights over the coming months.

Heatwaves are also more likely to occur, and the risk of bushfires increases.

The last El Nino was in 2016. They generally last during spring and summer before falling away. But they can then return for multiple years. This El Nino is due to peak in January – high summer.

Enter the IOD

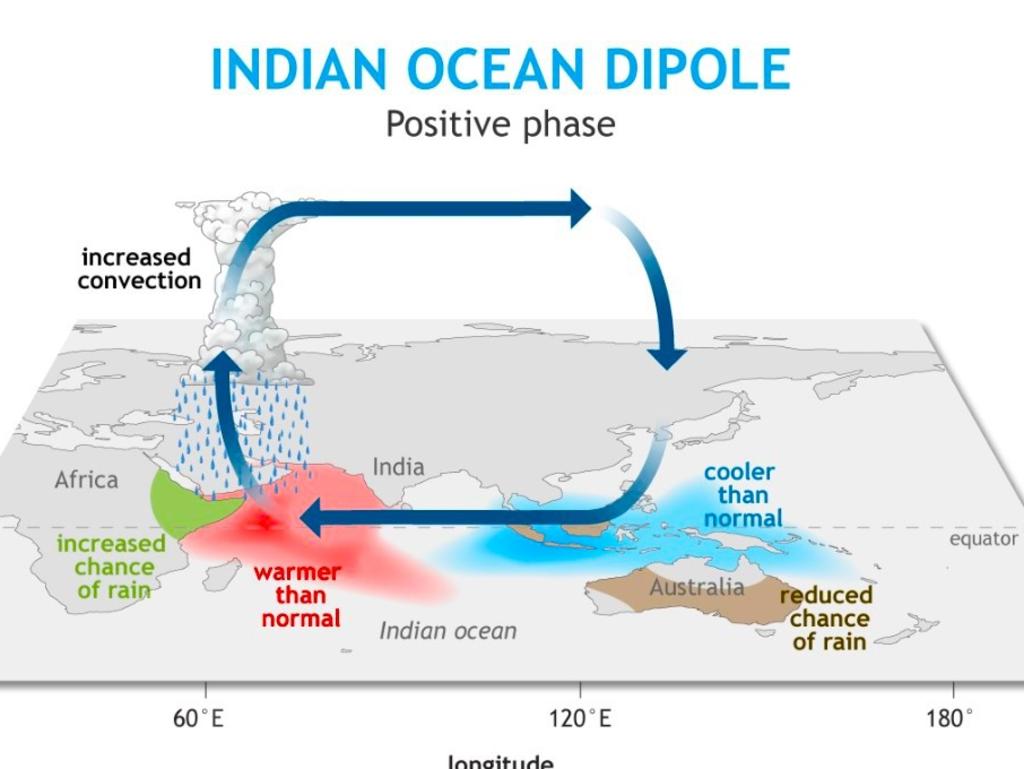

But this time around, El Nino is not the only climate driver in town. It’s bubbling up at exactly the same time as the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is in a positive phase.

“That the positive IOD and El Nino are joining forces increases the odds of drier weather for much of the country – particularly over inland regions,” Sky News Weather meteorologist Rob Sharpe told news.com.au.

“Positive IOD events particularly enhance the heat through the final few months of the year in those regions – just like we saw in 2019 when we last saw a positive IOD.”

Whereas El Ninos primarily affects eastern Australia, the IODs also impact central and southern Australia too, potentially magnifying the pain.

“South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and New South Wales all face significant influences from both El Nino and positive IOD events – both enhancing the warming and drying trend for much of these regions,” said Mr Sharpe.

‘Worst since Black Summer’

Worryingly, one of Australia’s worst bushfire seasons – 2019’s Black Summer – was during a positive IOD event. It led to 34 deaths and destroyed over 3000 buildings.

And that was without the added oomph of an El Nino. This summer will have both.

However, most weather watchers doubt summer 2023/24 will be as catastrophic for bushfires as 2019.

They point out that 2019 followed several years when Australia was parched. Right now, Australia has just come out of a three-year soggy spell of La Nina.

But that doesn’t mean Australia can relax – not by a long host.

“I’m not a betting man, but if I was I’d say we’re going to get big fires this year,” Mr Mullins, who is a founder of Emergency Leaders for Climate Action, a group of ex-fire and SES chiefs who lobby for stronger polices on climate change, said in July.

“Not like Black Summer, but we will have days, perhaps a number of days in a row, periodically, where we lose homes.”

Sky’s Mr Sharpe agreed there was cause for concern with high fuel loads in some areas that were already drying out.

“The fire season that is now underway in much of the north and east could be very dangerous. “At this stage we are thinking it will be the worst since Black Summer, but likely falling short of its extent,” said Mr Sharpe.

“Having said that, it only takes one major fire to create a disaster – as we saw in Maui.”

The last time a positive IOD coincided with an El Nino was in 2015. This became the fifth warmest year in Australia on record – that feat has been surpassed since then.

The climate event included Australia’s warmest October on record.

But rainfall was only slightly below average, which shows that you can’t totally predict how much of an influence the various climate drivers will be.

How the El Nino and the IOD work

So, what mechanisms are actually at play when we talk of El Nino and the Indian Ocean Dipole?

The first thing to note is they are essentially the same phenomena.

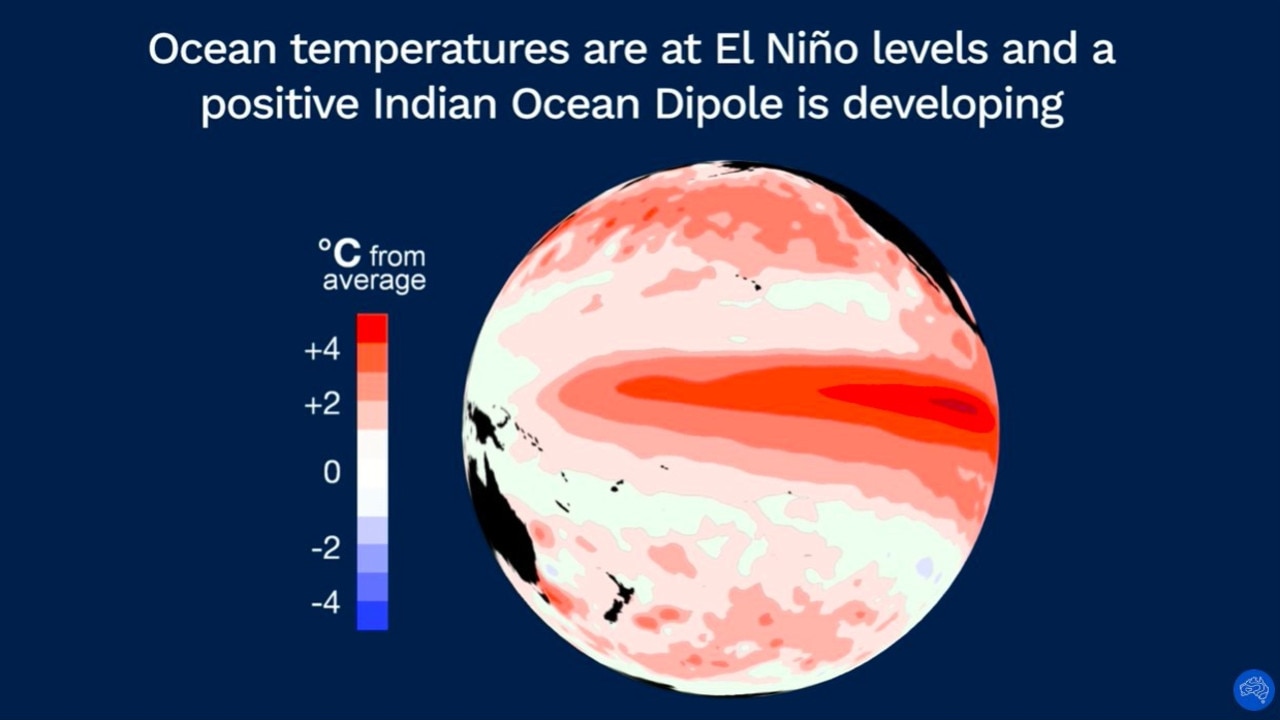

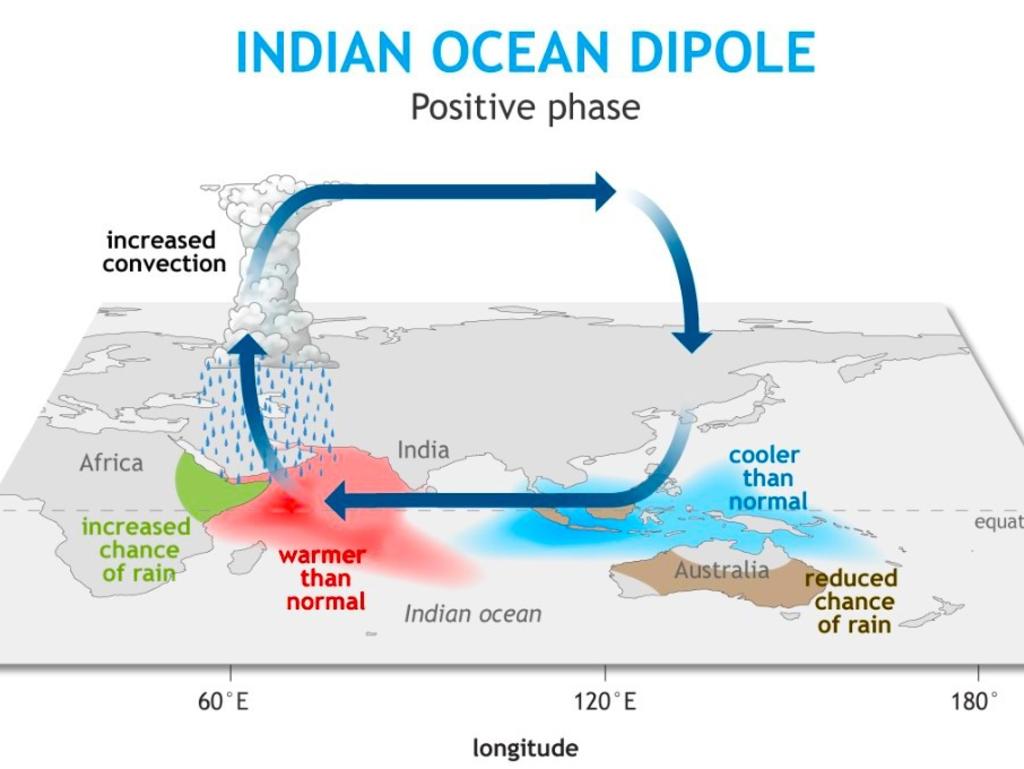

These climate drivers are both a measure of how winds and water interact. The difference is El Nino is in the Pacific and the IOD is in the Indian Ocean.

El Nino – in Spanish it means “little boy” – is the name given to one extreme of the El Nino Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. At the other extreme of ENSO is La Nina, or “little girl”.

It’s a natural cycle that swings between El Nino and La Nina, but when exactly it shifts and to what strength it reaches does vary.

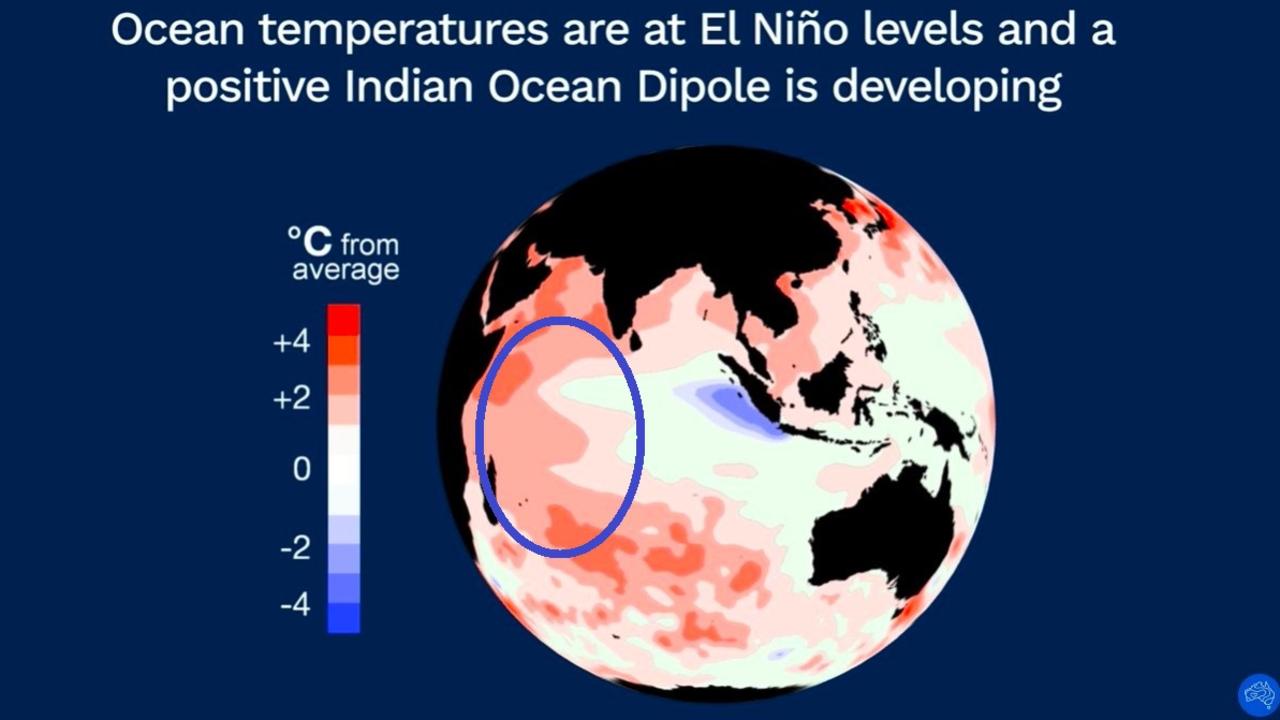

Most metrological organisations measure the ENSO by sea surface temperatures. An El Nino is declared when the waters are 0.5C above average in an area of the Pacific.

This yardstick was reached months ago, leading the US’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to declare El Nino in July.

But the BOM is stricter. Not only does it want to see water temperatures rise higher, to 0.8C above average, it also demands a coupling of that with a specific measure of atmospheric pressure.

That has only happened recently.

When ENSO is in neutral – between La Nina and El Nino – trade winds blow from east to west, pushing warmer waters towards Australia that aid in the formation of clouds and average spring and summer rain for the country’s east.

When El Nino powers up, those trade winds can weaken or even reverse. Less warm water reaches us, so there are fewer clouds — and that can pare back rainfall.

The BOM has predicted that sea temperatures could reach their peak, 2.8C above normal, in January.

The IOD is also all about winds and water too. In a positive phase, like now, warmer waters are closer to Africa, aiding rainfall in that continent’s east and depriving it from Australia.

More Coverage

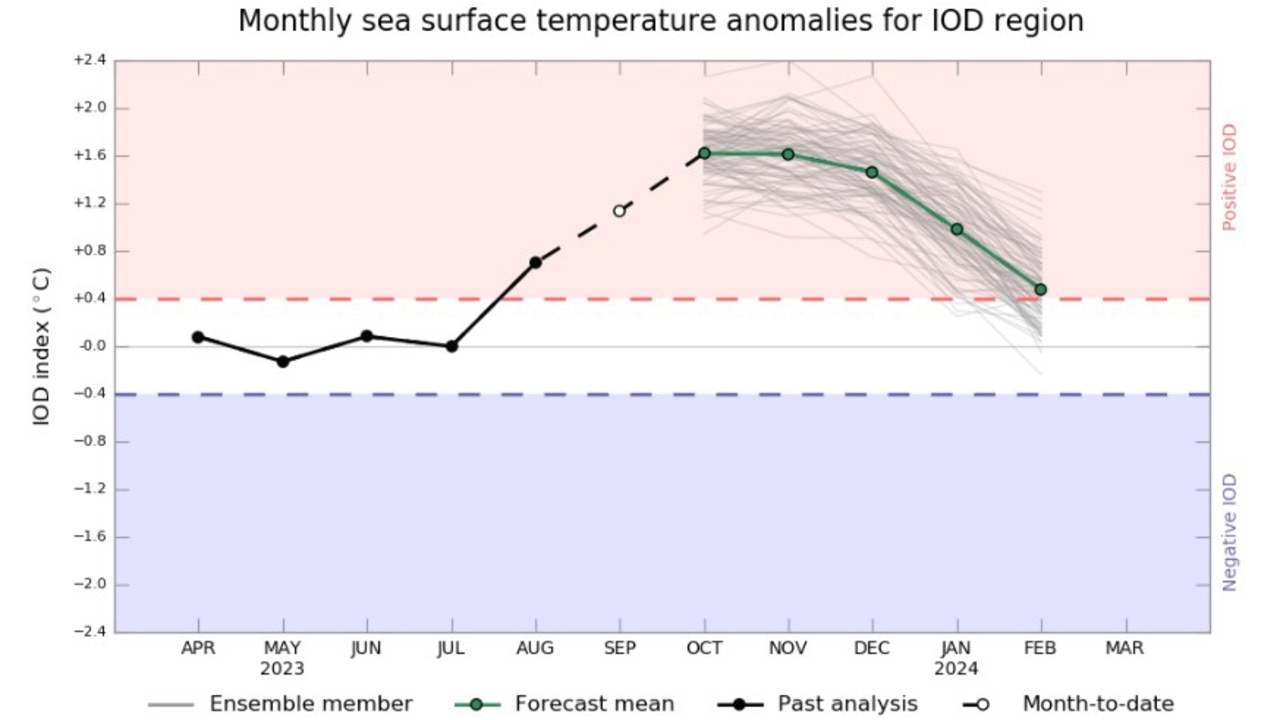

Positive IODs don’t last long as El Ninos. Spring will be affected by it but it usually tails off during summer when the northern monsoon arrives.

This year’s El Nino formation is good news for eastern Africa and parts of the Americas, which will likely see much-needed rainfall.

But for Australia, with its double whammy of El Nino and the IOD, strap in for a scorching summer and all the risks that could bring.