Why Australia disagrees with world on El Nino

The UN has just declared a major weather change to be official, as has the US, which will affect Australia. But the BOM has other ideas.

It looks like an El Nino and feels like an El Nino, and two of the world’s major meteorological associations have declared we are, indeed, in an El Nino.

But not Australia’s own Bureau of Meteorology which has steadfastly insisted the climate driver, which often brings parched conditions, is not yet upon us.

When it comes to El Nino, Australia out of kilter with the rest of the world.

The latest El Nino announcement has come from the United Nations’ own World Meteorological Organisation (WMO).

On Tuesday, it said the 2023 El Nino was now official – the first time it had appeared since 2016.

Grim warning

“The onset of El Nino will greatly increase the likelihood of breaking temperature records and triggering more extreme heat in many parts of the world and in the ocean,” said WMO secretary-general Professor Petteri Taalas.

“Early warnings and anticipatory action of extreme weather events associated with this major climate phenomenon are vital to save lives and livelihoods,” Prof Taalas starkly warned.

The last El Nino contributed to 2016 being the hottest year on record. On Monday, the globe saw its hottest ever day as the new El Nino cranked up.

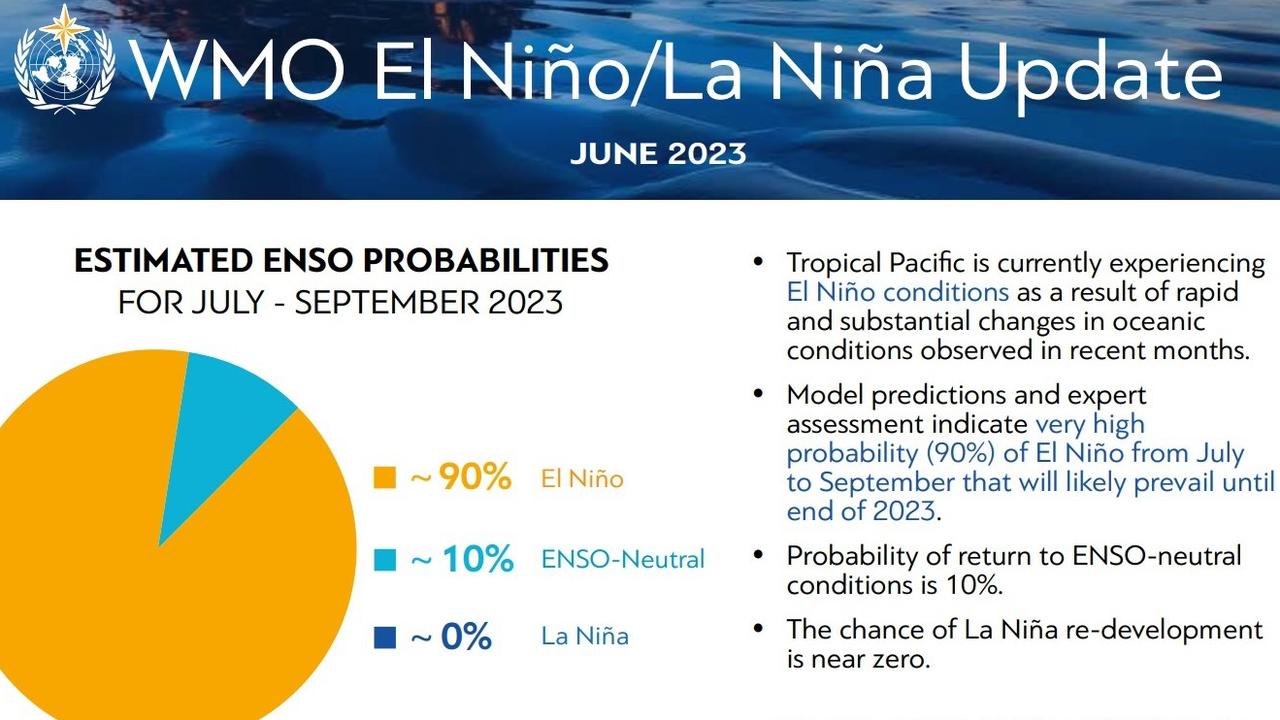

The WMO said there was now a 90 per cent probability the El Nino would last into the second half of 2023 and would be of at least moderate strength.

El Nino is one extreme of a Pacific Ocean climate driver called the El Nino Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. At the other end of ENSO is La Nina.

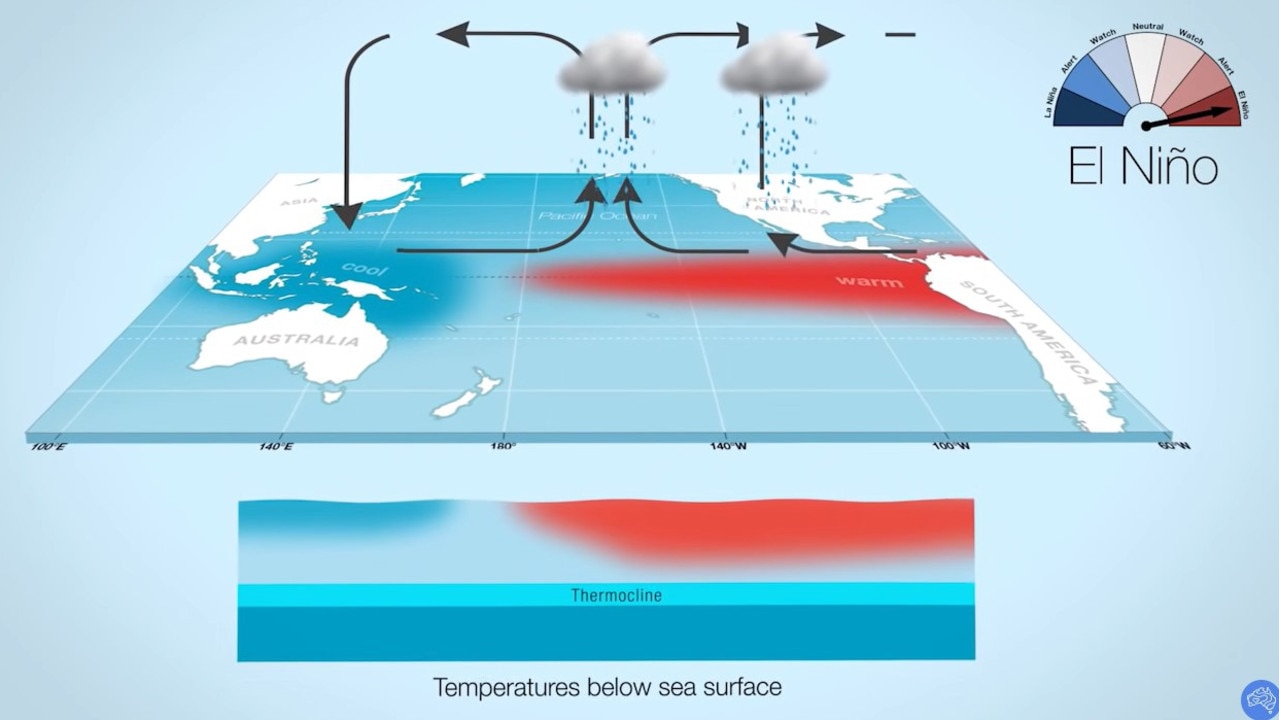

During El Nino, the temperature of a specific area of the central and eastern Pacific – called Nino 3.4 in meteorological circles – rises.

This aids in the creation of clouds and rainfall there, rather than over Australia which in turn can lead to drier conditions and drought for the country.

Conversely, when a La Nina takes over sea surface temperatures fall which ups the likelihood of rain over Australia.

Australia disagrees – no El Nino yet

The WMO’s El Nino declaration has come a month after the US’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said the same.

NOAA and the BOM are the two global meteorology agencies that most look too for El Nino and La Nina declarations.

But a climate driver update released by the BOM on Tuesday – the same day as the WMO’s announcement – said the outlook remained at “El Nino Alert” which is still one step away from a full El Nino.

The disparity in calling El Nino is down to the fact that the BOM has a slightly different definition of the climate driver and is stricter when it comes to the level sea surface temperatures have to reach.

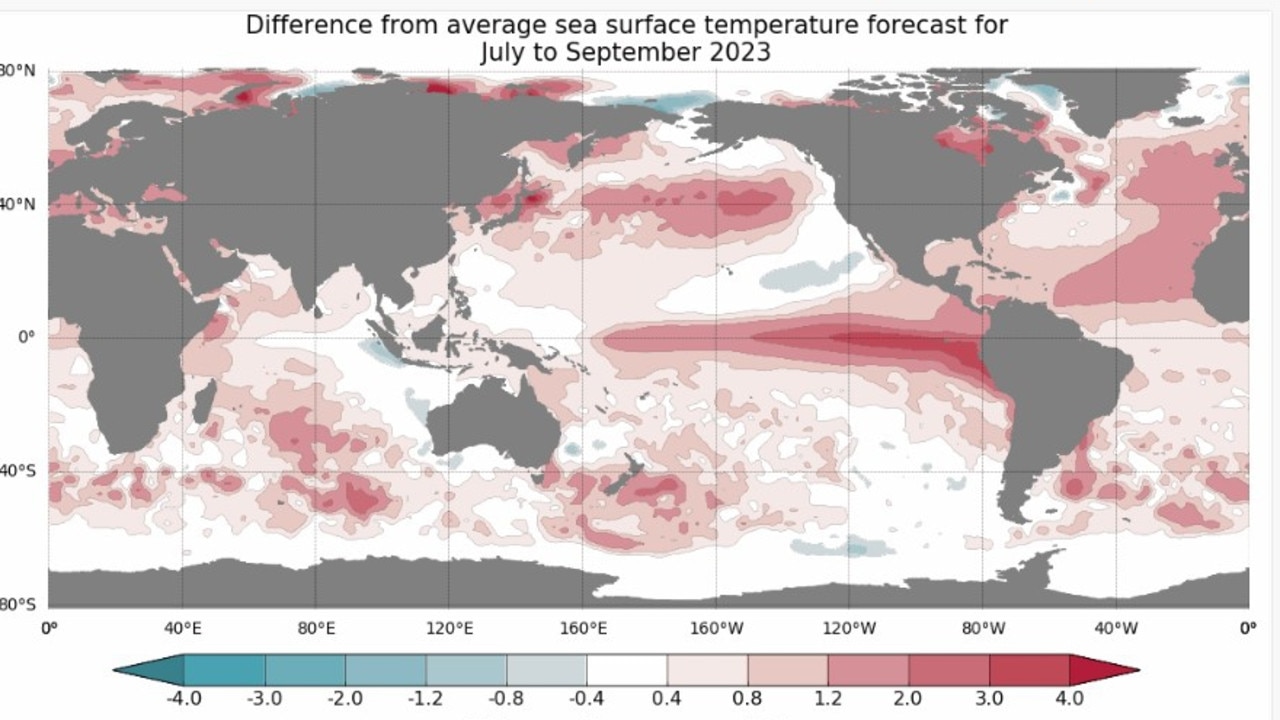

NOAA calls El Nino when sea surface temperatures at Nino 3.4 are 0.5C warmer than normal with conditions expected to last for another five months at least.

The BOM needs it to be hotter – as much as 0.8C.

The Bureau said on Tuesday that sea surface temperatures had indeed risen high enough to have exceeded the El Nino threshold.

However, it added, “sustained changes in wind, cloud and broadscale pressure patterns towards El Nino-like patterns have not yet been observed”.

“This means the Pacific Ocean and atmosphere have yet to become fully coupled, as occurs during El Nino events.”

As far as the BOM’s concerned we’re just not quite at El Nino yet – but all the signs are pointing in that direction. There is a 70 per chance of El Nino Alert periods transitioning to full El Ninos.

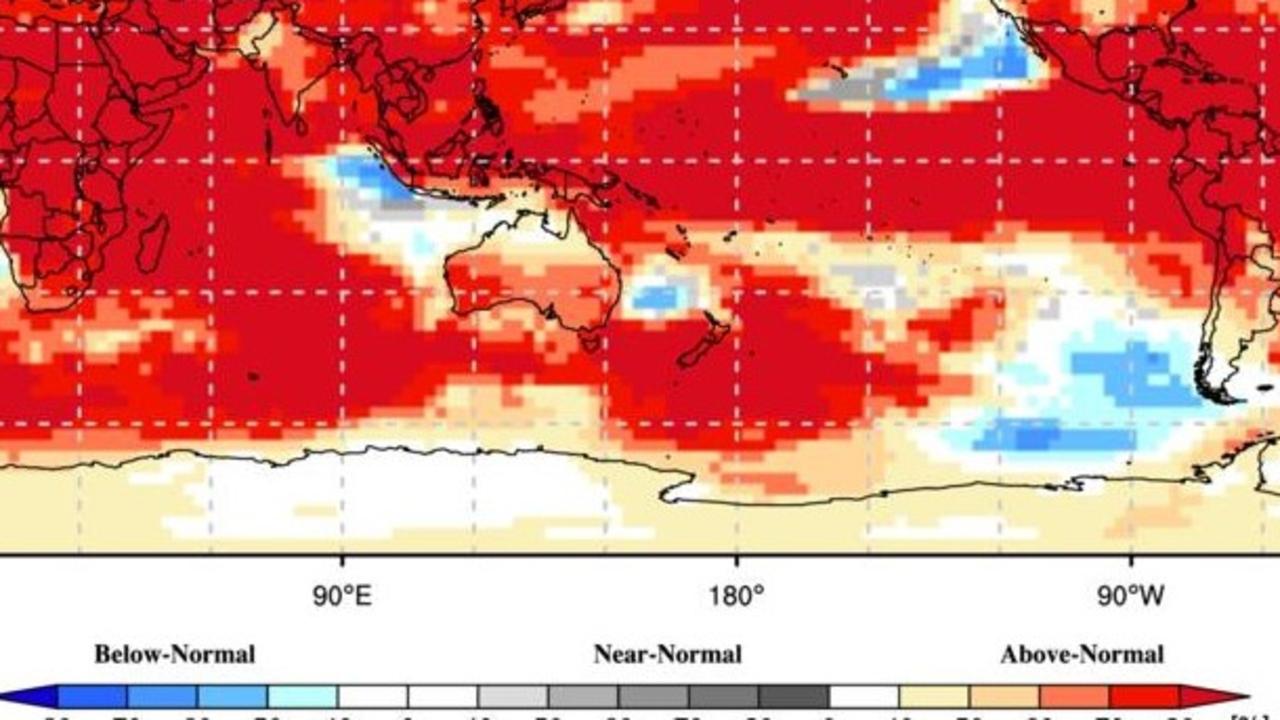

“The current status of the ENSO Outlook does not change the long-range forecast of warmer and drier conditions across much of Australia for August to October,” the BOM stated.

A particularly grim forecast will be if El Nino occurs at the same time as another key climate driver – the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) off Western Australia – turns positive.

This scenario is becoming increasingly likely, the BOM has said.

“A positive IOD typically suppresses winter and spring rainfall over much of Australia, and if it coincides with El Nino, it can exacerbate El Nino’s drying effect.”

The BOM said climate change “continued to influence” the Australian climate.

“Global sea surface temperatures were the warmest on record for the months of April and May, and the warmest on record for the Australian region during June.

“The Australian continent has warmed by around 1.47C over the period 1910 to 2021.

“There has also been a trend towards a greater proportion of rainfall from high intensity, short duration rainfall events, especially across northern Australia.

“Southern Australia has seen a reduction, by 10 to 20 per cent, in cool season (April to October) rainfall in recent decades.”