Cunningham: What will save Alice Springs amid continuing crime

Twelve months ago the nation watched in shock at the crime crisis unfolding in Alice Springs. Has anything changed, Matt Cunningham asks.

The line outside the bar extends almost 30 metres down Todd Street.

It’s just before 1pm on a Thursday afternoon and the doors of this Alice Springs pub are just about to open. Every person in the queue is Aboriginal.

Most are of working age. As the doors open they file inside.

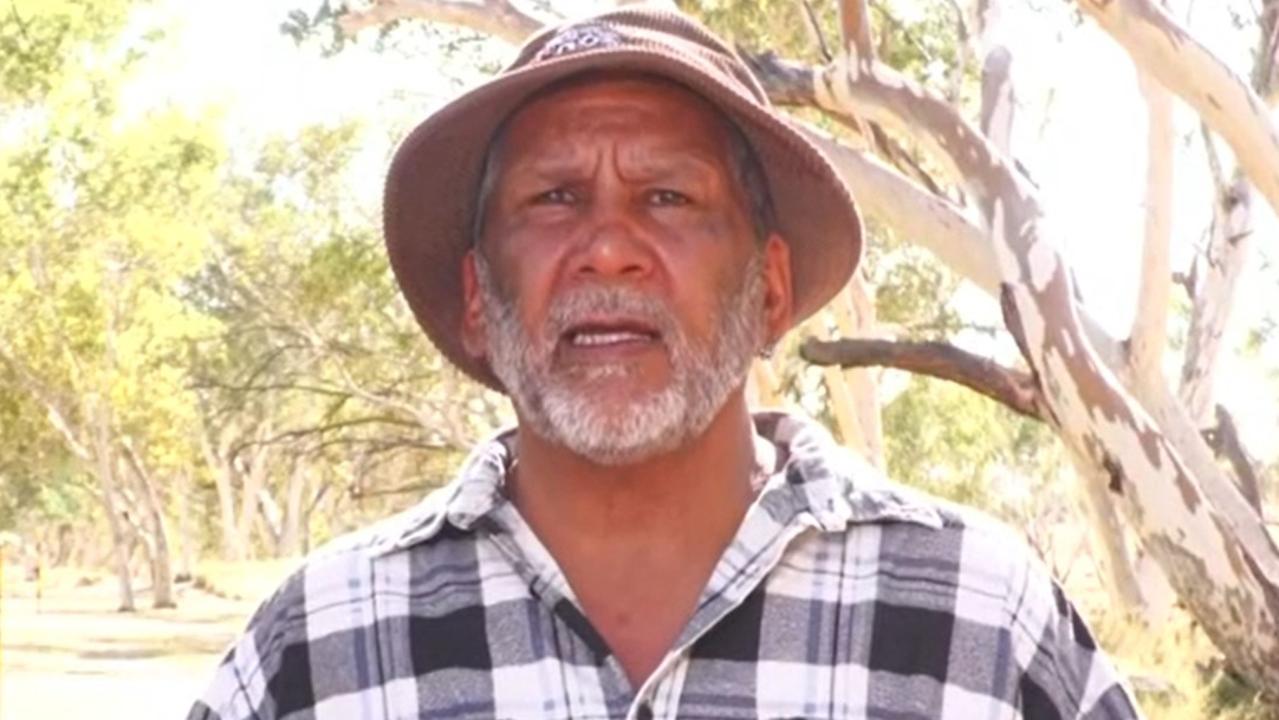

“You have a long line at Centrelink and a long line at the banks and a long line at the pubs,” says Michael Liddle, an Alyawarre man who has live his entire life in Central Australia.

“There has to be a connection there. There’s not a long line at the schools.”

The bottleshops won’t open for another two hours.

Their operating times were limited after Prime Minister Anthony Albanese flew into town last January and forced the Northern Territory government to act.

Takeaway sales were banned completely on Mondays and Tuesdays.

Hours were restricted to between 3pm and 7pm on other weekdays. But the grog hasn’t stopped flowing. It’s just moved inside the pub.

Publicans from several venues say Mondays and Tuesday have become their busiest days.

Twelve months ago the nation watched in shock at the crime crisis unfolding in Alice Springs.

Has anything changed?

It’s a difficult question to answer, because if things are any better, they’re still a long way from good.

But the town’s problems are certainly attracting less national attention than in 2023, when Australians were preparing to vote in a referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. Alice Springs became a focal point in that debate.

NO supporters wondered how the federal government could waste so much time and money on a referendum while the issues playing out in Alice went unaddressed.

YES campaigners said Alice Springs was proof something needed to be done differently.

In 2024 Alice Springs seems to have been forgotten, as our leaders focus on other things, like whether Woolworths should sell Australia Day products.

But the town’s problems are far from resolved.

The most significant changed forced by the Prime Minister last year was the reinstatement of intervention-era alcohol bans in Aboriginal town camps.

When the bans were lifted in July 2022 there was an immediate increase in alcohol-related assaults, domestic violence and hospital admissions.

Police say those incidents are down on this time last year.

“December last year we were attending more than 700 domestic violence incidents a month, whereas December just gone in 2023 that was in the mid- 500s,” says Acting Assistant Commissioner James Gray-Spence.

More than 500 for a town of about 25,000 people would still be considered catastrophic in most other parts of the country.

But Commissioner Gray-Spence says the drop in domestic violence cases has allowed police to divert more resources to another type of crime that’s been growing at a rapid rate.

Property crime is at an all-time high.

House break-ins are up 260 per cent since 2016.

Commercial break-ins are up 164 per cent over the same period and almost 20 per cent over the past year.

The Todd Mall, once a bustling tourist hub, is lined with boarded-up windows and roller shutters.

Former NT Labor MP Scott McConnell has an office in a laneway just off the mall.

“The real crisis we have now is a crisis of confidence,” he says.

“People in Alice Springs are scared. They’re worried about their future. They’re worried about their safety on the streets. They’re worried about the future of the economy. They’re worried that the tourism industry has collapsed.”

Mr McConnell, who was elected in Labor’s landslide victory in 2016, is scathing of his former colleagues and their neglect of remote Indigenous communities.

He points to the closure of police stations and health clinics in his former electorate which covers 383,000 square kilometres of land west of Alice Springs.

He says the neglect of those communities is now playing out on the streets of Alice Springs, as residents who have few services and little to do, head into town and often cause trouble.

“I’ve lived in and around Alice Springs for most of my life and I’ve never seen it like this before,” he says.

The urban drift Mr McConnell speaks about is perhaps best illustrated late at night.

Alice Springs businessman Darren Clark takes us for a late-night tour of the town.

In the CBD, dozens of children, some as young as eight or nine, can be seen wandering the streets unsupervised well after midnight.

Car thefts have become a regular occurrence.

On Wednesday night two cars are stolen. One is caught on film hooning around the streets at 5am with five teenagers hanging out the windows.

“It’s going to end in tragedy,” Mr Clark says.

“People keep shaking their heads that it hasn’t happened yet, but one of those cars is going to plough into an innocent person’s vehicle. Something tragic is going to happen and none of us want to see that.”

As part of its “Summer Plan” announced late last year, the Northern Territory government committed to removing at-risk children from the streets and taking them to a safe place until a responsible parent or carer could be located.

This has been a complex issue for governments, with activists claiming too many Aboriginal children are being removed from their families.

But, speaking before Christmas, NT Police Minister Brent Potter was unapologetic.

“I don’t think it matters if you’re Indigenous or non-Indigenous, if you’re a kid that is at risk, you need to be pulled from that home environment until we can put the intensive programs around the parents and around the child,” he said.

“It shouldn’t matter whether you come from a particular demographic, it’s about protecting children and a child who is out on the street at night-time, after dark without a parent supervising them, that is a child at-risk and we know that when a child is out doing that there is all the likelihood that it leads to criminal behaviour. It is incumbent on the government to protect the children in the community.”

On Thursday, Mr Potter issued a statement saying police engaged with 31 at-risk children on the streets of Alice Springs, Darwin and Palmerston in the past month.

That seems far fewer than the number of at-risk children – by the Minister’s own definition – we saw on the Alice Springs streets in three hours this week.

Mr Potter says another 165 children have been engaged and supported through youth outreach and re-engagement teams.

Warlpiri man and former school teacher Anthony Egan says Aboriginal people have lost the agency to deal with their own children.

“There’s no control over the kids roaming at night,” he says.

“They need to give us the lore back. We should be making our rules, not the government. We need to control our kids, not white people.”

Mr Egan says many Aboriginal people from Central Australia are lost, as they try to walk between two worlds.

“Look at all my people in the creek,” he says.

“We don’t fit in with anybody. Where do we fit in?”

He also points to the scourge of royalty money saying it often leads to violence.

“Where does that money go,” he says. “The people spend it wrongly. We kill over royalty money.”

Mr Liddle says parents need to take more responsibility.

“Where is mum and dad?” he says. “Where is the person that gave birth to that child. We’re not talking about objects here, these are human beings. Do mum and dad think about that when they’re at the pub?”

Mr McConnell says efforts now need to be directed at the next generation.

“What’s going to save us is getting Indigenous children in remote communities to school,” he says, pointing to school attendance rates in his old electorate of less than 30 per cent.

He says the low school attendance is robbing Central Australia of a trained and educated workforce.

“Alice Springs could have an expanding tourism industry, instead of a collapsing one, but we need to have an accessible workforce. That workforce needs to be local workforce, it needs to be an Indigenous workforce, and the only way we can create that workforce is by increasing the school attendance.”

For Mr McConnell, the town he grew up in is a town worth saving.

More Coverage

“Alice Springs is a great place,” he says.

“People watching the coverage of Alice Springs who are really crestfallen and worried about us, please support us. Please keep up the pressure to have something different and something better done.”

Matt Cunningham is Sky News’ Northern Australian bureau correspondent.