‘Wanted attention’: Appalling questions rape survivor was asked

Boyd Kramer was found guilty of rape in 2022. But the questions his victim was asked in court are guaranteed to sicken you.

OPINION

This week, news.com.au shared Madeline Lane’s story as part of the Justice Shouldn’t Hurt: Take the Stand campaign.

Ms Lane, who was raped by Boyd Kramer in 2020, spent three days on the stand in the 2022 trial held in the New South Wales District Court, which ultimately resulted in a guilty verdict.

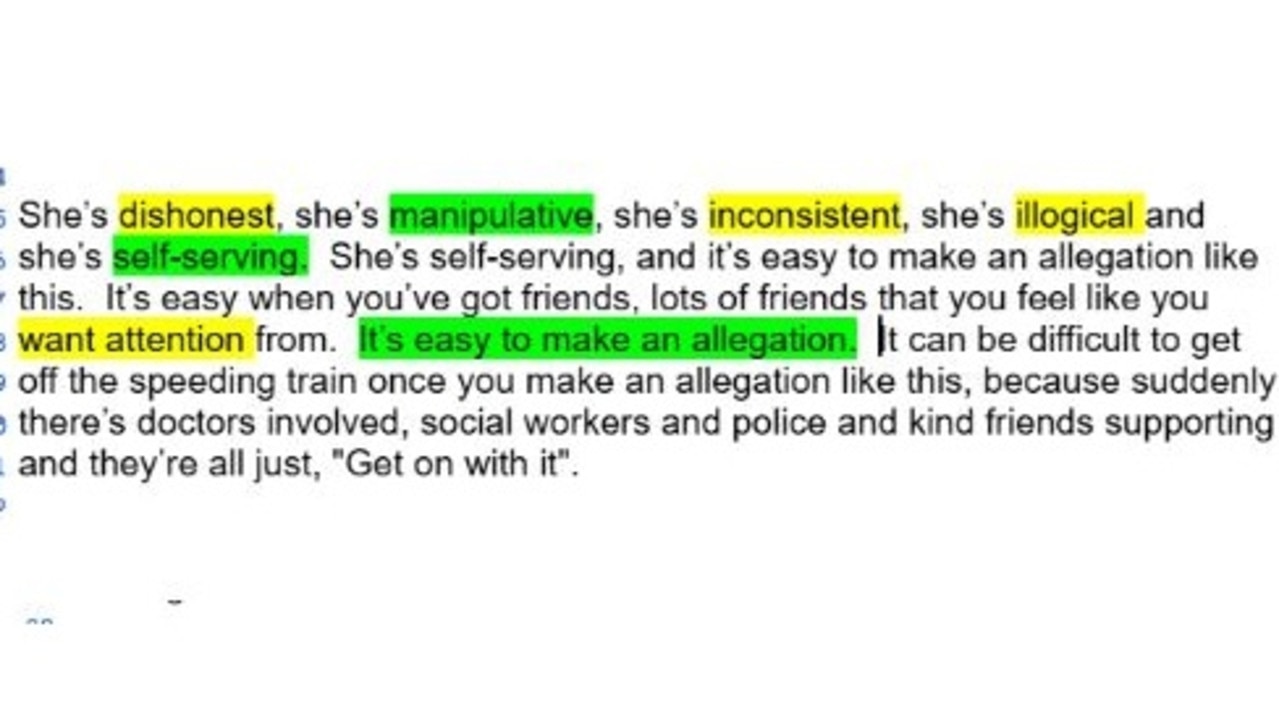

According to journalist Nina Funnell, who analysed the trial transcript with Ms Lane’s permission, Ms Lane was asked more than 1500 questions, and was labelled “dishonest”, “manipulative”, “wicked”, “flirtatious”, a “liar” and an “attention seeker” who “exaggerates” for “sympathy”.

She was also asked to discuss her “favourite sexual position”, if she wore underwear, and to describe the style of underwear she wore the night of the rape.

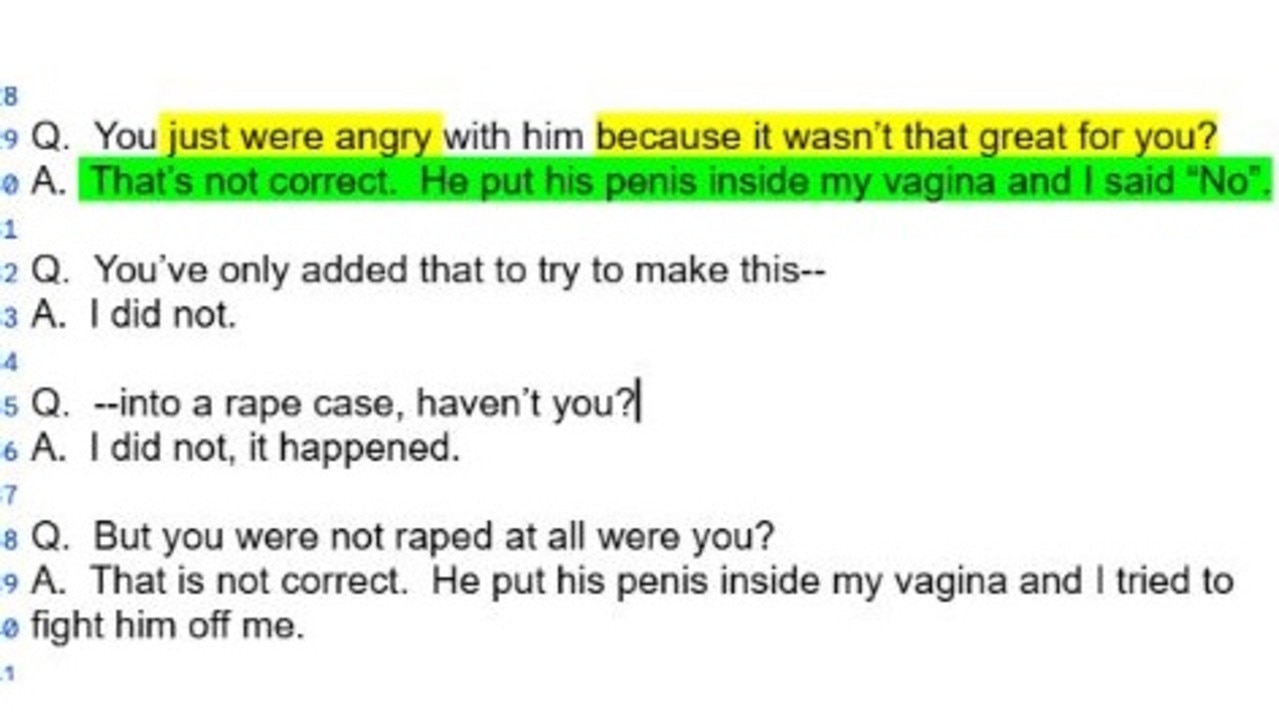

As is common in Australia’s adversarial legal system, the rapist’s lawyer, Margaret Cunneen, under cross examination, suggested Ms Lane fabricated the rape either “for sympathy”, “attention” or – bizarrely – out of “resentment” for not orgasming.

Ms Lane was also asked repeatedly why she didn’t “try to leave” or do more to stop her rape. At two points, she was asked to physically re-enact how she fought off her attacker.

“It was extremely humiliating and traumatic,” Ms Lane told Ms Funnell.

“The rape was an attack on my body but the criminal process was an attack on my soul.”

As an academic, I have spent eight years analysing court transcripts of rape cases. This is not always easy, as transcripts can be notoriously difficult to obtain.

Victim-survivors themselves cannot always obtain the transcript, and because they are not a party to proceedings, they are not automatically entitled to a copy. I am aware of cases where victim-survivors were blocked or asked to pay thousands of dollars for a copy of the transcript of the trial.

Donate to help survivors obtain their court transcripts here

In Ms Lane’s case, she had to engage her own lawyers to apply for the transcript.

This lack of access and lack of transparency around court transcripts makes it very difficult to know exactly what is happening in courtrooms across Australia in rape trials. Cuts in funding across the media industry also mean there are fewer court reporters to attend and cover what is happening in our courts.

That is why having a transcript like Ms Lane’s is so illuminating and instructive. It’s also why projects like Funnell’s Take The Stand – which has followed 20 cases including Ms Lane’s – are so important.

As news.com.au reported on Monday, Ms Lane’s evidence spanned 150 pages.

Legally, she is considered a witness to her own rape. This means that in court, she could not share the experience in her own words. As a witness, she can only answer the questions asked of her. If she strays too far from the answer they want, she is cut off. Silenced.

Ms Lane said cross-examination by her rapist’s lawyer, Margaret Cunneen, is one of the most “humiliating” things she has ever experienced. Afterwards, she vomited in the court bathrooms.

During cross-examination by Cunneen, who also represented Jarryd Hayne, Ms Lane had been called a “tease” and accused of making up the rape because she “wanted the attention”. She was also asked to stand up and imitate how she tried to push her rapist, Boyd Kramer, off her.

Ms Lane’s experience aligns with what other victim-survivors of sexual violence often tell us – that the trial is as bad as the rape. Re-traumatisation by the criminal justice system is a common experience. Under questioning, a victim-survivor’s credibility and character are attacked by the defence.

The law sets boundaries around what questions can be asked of witnesses, including victim-survivors, during cross-examination.

To enforce these rules, judges in NSW are required (by section 41 of what is known as the Uniform Evidence Act) to intervene if questions asked of witnesses are: “misleading or confusing”, or “annoying, harassing, intimidating, offensive, oppressive, humiliating or repetitive”.

The Act also disallows questions that have “no basis other than a stereotype”, and judges are required to intervene if questions are asked of a witness “in a manner or tone that is belittling, insulting, or otherwise inappropriate”.

Judges must disallow all these questions, such as through objecting or directing the witness not to answer; it is a positive obligation. That is, it is not merely a power that a judge can wield at their leisure – they must intervene into such questioning where it falls into any of these categories.

Yet, as I have often observed when analysing court transcripts, judges are routinely failing in this obligation.

Many reasons are spouted for this failure. Common among them is the purported desire to avoid convicted rapists appealing a jury’s guilty verdict.

To explain, there is a common belief among some in the judiciary that if judges intervene too often when the defence is cross-examining a witness, this might give the defence grounds for appeal later, as it could appear the judge was biased against the defendant or overly sympathetic to the prosecution’s case.

Some judges claim that the decision not to intervene is therefore virtuous, as appeals can be retraumatising for victim-survivors, who again have their lives anxiously put on hold, and must relive their experience of sexual violence.

This is certainly true. Appeals draw out an already long legal process for victim-survivors.

But the answer is hardly in judges staying quiet, and allowing defence counsel to humiliate and traumatise a victim-survivor right there in front of them in court.

Instead, it’s time for specialist judges to be introduced. They enforce the rights of victim-survivors’ not to be misled, confused, annoyed, harassed, intimated, offended, oppressed or humiliated. Section 41 should prevent victim-survivors from being peppered repeatedly with the same questions, belittled, insulted, spoken to inappropriately or otherwise stereotyped because of their sex, race, culture, ethnicity, age or mental, intellectual or physical disability.

As they say, the standard you walk past is the standard you accept.

Dr Rachael Burgin is chief executive of Rape and Sexual Assault Research and Advocacy (RASARA) and a senior lecturer in Criminal Justice at Swinburne University of Technology

Read related topics:Take The Stand