Sydney’s latte line that hides city’s 'shameful secret’

It’s the line referred to with a chuckle that slices through Sydney. But the issues that lie on one side are no joke and will take billions to fix.

It’s known by various names — all seemingly designed to elicit a chuckle. To some it’s the “latte line”, to others the “quinoa curtain”.

But for one of the leading voices in western Sydney, the line that divides Australia’s largest city in two is nothing to laugh about. Rather, among other woes, it hides one of the “shameful secrets of Sydney”.

That’s the opinion of Christopher Brown, Chairman of the Western Sydney Leadership Dialogue (WSLD), a group bringing together public and private sector bodies to focus on the issues facing the city’s west.

He told news.com.au huge investment will be needed in education, health services and transport to broach the wall that splits the city.

With more than two million people living in western Sydney, if it were a city in its own right, it would be Australia’s fifth largest.

It’s expected to grow in population by more than a million people by 2030 and it already is the third biggest economy in the country with an economic output of $114 billion annually.

Yet, western Sydney can seem a world away from the wealthier, eastern side of the city which is famed for its skyscrapers overlooking the harbour and golden beaches at Bondi.

An imaginary line, the location of which is hotly disputed, that marks the beginning of Sydney’s west is known by several names. A favourite is the “Red Rooster line” in reference to the takeaway chicken chain which has the vast majority of its Sydney outlets in the west.

“If you don’t know the latte line, or as I call it the Colorbond fence, it starts near the airport and goes diagonally across the city,” said Mr Brown at the WSLD’s Out There summit, held in Bankstown last week.

It passes through Parramatta, where house prices are far more expensive north of the major hub than south of it, before continuing north west dividing the Hills District from Blacktown.

‘SHAMEFUL SECRET’ OF WESTERN SYDNEY

On the plus side, Mr Brown said, western Sydney was brimming with cultural diversity, Parramatta is already the state’s second largest CBD and the new Western Sydney Airport is under construction.

But there were far too many downsides.

“As much as we are strong advocates of western Sydney, we need to be realistic that too many times we are on the wrong side of that line. In terms of per capita lower incomes, below average NAPLAN results and school attendance, higher unemployment and higher rates of preventable disease and hospital admissions.

“Western Sydney is the diabetes capital of the country,” he said.

“There are also higher rates of domestic violence which is the shameful secret of western Sydney. We still keep beating up our loved ones more than anywhere else and we have to stop it.”

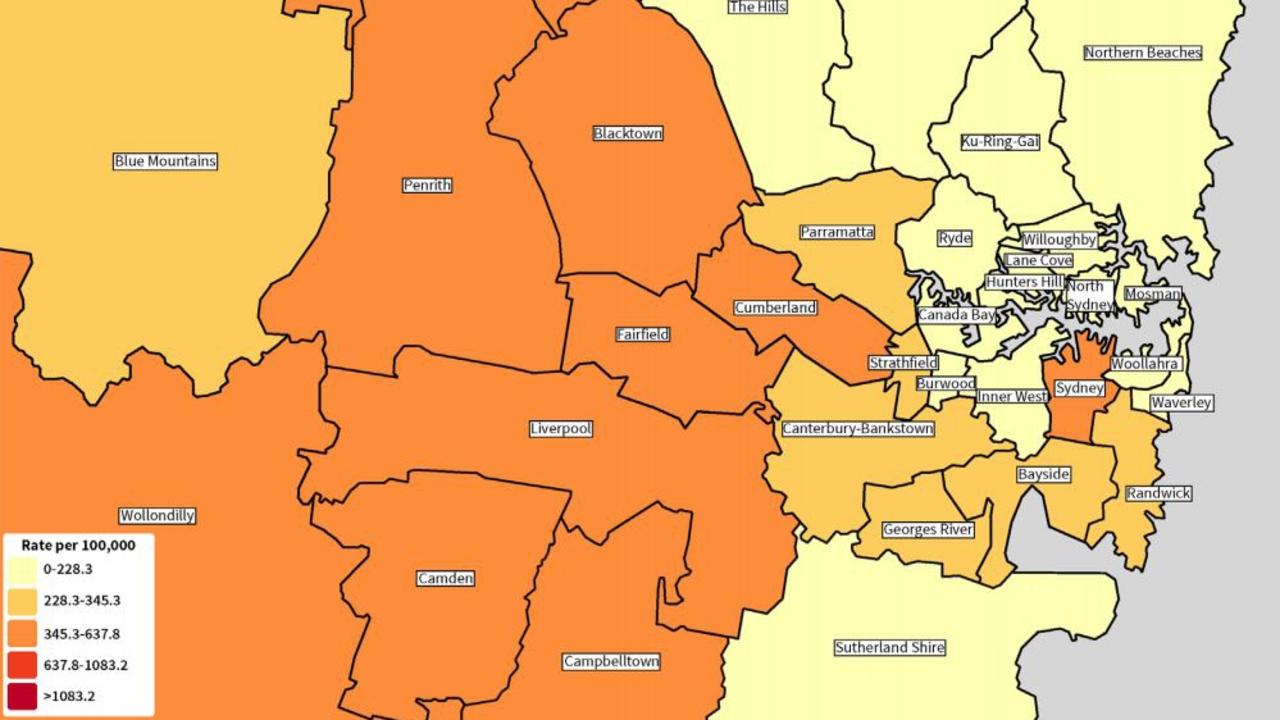

A report by the WSLD, published earlier this year, found the greater western Sydney area accounted for 51 per cent of the city’s population but 59 per cent of the incidents of domestic violence.

Rates of reported domestic violence per-capita in Campbelltown, Blacktown and Penrith were double those throughout most of Sydney’s east.

The organisation noted that western Sydney had a high indigenous proportion and Aboriginal women were four times more likely to experience domestic violence than non-indigenous women.

Pregnant women, women with disabilities, young women and women under financial strain were all at increased risk.

There was “no simple solution” to tackling the crime in western Sydney, the WSLD said. But it has recommended paid domestic violence leave; $20 million to implement a primary prevention public health model around family and domestic violence and a Royal Commission into the issue.

BREAKING DOWN THE LATTE LINE

Important as it was, tackling domestic violence was only one factor in bridging the latte line, said Mr Brown. Improved healthcare and access to employment was also high on the list.

“A lot of the jobs are in the more advantaged parts of city which are on the other side of the Parramatta river.

“That’s one of the reasons why we need a north south rail connection so it’s easier for people living in Bankstown to get to a job in Parramatta, Norwest or Ryde.”

This outer Sydney rail line, which would link Kogarah and Epping via Bankstown and Parramatta bypassing the Central station, is listed as a longer term infrastructure aim by the Greater Sydney Commission (GSC). This is a body set up by the NSW Government to look at land use in a city that is expected grow from five to eight million people in the next 40 years.

However, an even more pressing chunk of infrastructure, the Commission has said, is the planned Metro West line from Parramatta to the city that would take pressure off the existing and slower rail route.

The NSW Government is looking to Canberra to tip in billions to help it become a reality. Asked by news.com.au if he backed this call, Mr Brown was effusive: “Yes, very much so, underline, several exclamation marks. You need federal funding, value capture, you need privatisation, you need some borrowing, and it’s that big that you need all four levers and then the fare box.”

GSC’s chief commissioner Lucy Turnbull, who is married to former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, was more diplomatic. She said a federal contribution would be “really helpful”.

“1.2 million people in western Sydney in the next 20 years is a reasonable forecast. It’s our job to make sure we do that it in a way that ensures liveability, productivity, sustainability and connectivity. Because if you’re well connected, you’ve got a huge advantage than if you’re not well connected spatially.”

She said places such as Parramatta and Bankstown represented the “future of Sydney and Australia” with a youthful and diverse population making them “exciting” corners of the wider city.

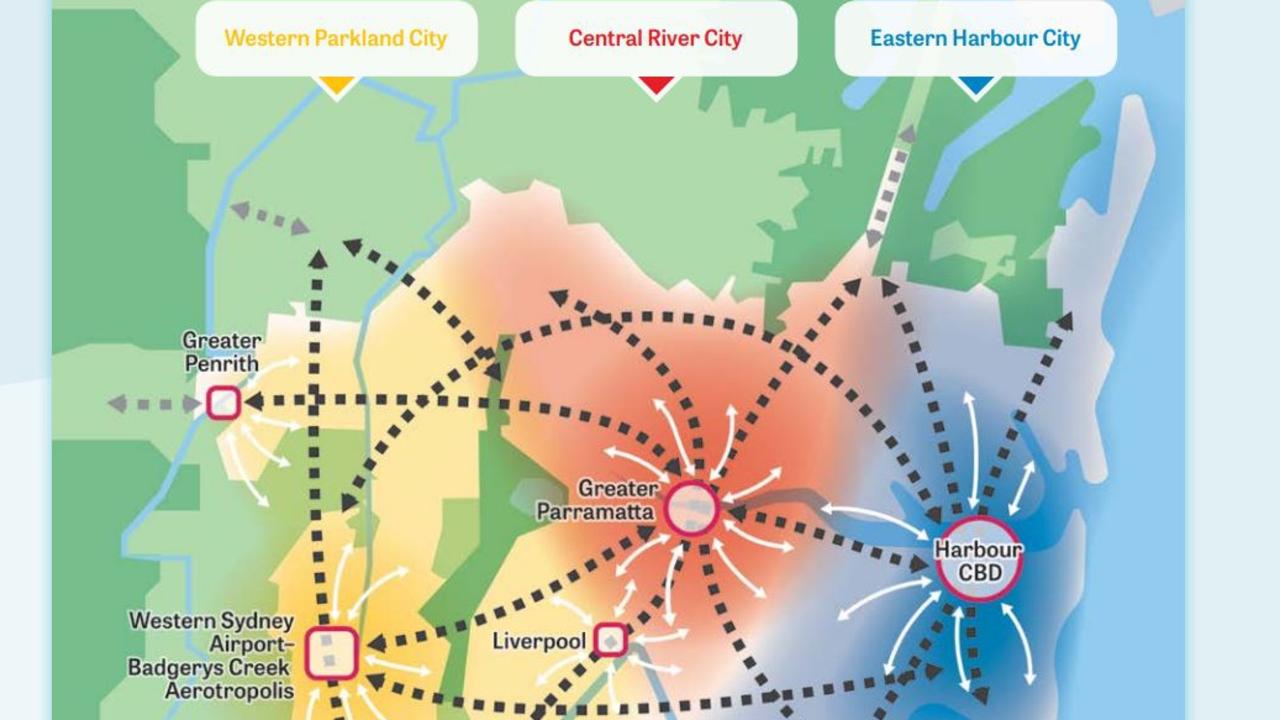

The GSC has proposed a new model for Sydney which would see the conurbation focused on three hubs.

The existing CBD is rechristened the Eastern Harbour City, the Central River City is centred on Parramatta with a Western Parkland City springing forth from the site of the under construction Badgerys Creek Airport.

The idea being that three hubs rather than one will make travelling to work, schools, universities and cultural pursuits simpler and spread the city’s population more easily.

“The Central River City would be the unifying heart of Sydney, not stuck in the middle.”

But Ms Turnbull told news.com.au the eventual aim was not to make passage across the latte line simpler — it was to get rid of it completely.

“We have to erase and eliminate that line over time so that where you live bears no relationship to what your prospects are, what your future in life will be, how well educated you will be, how healthy you will be, how likely you will be to go to university, what your income will be,” she said.

“To actually rebalance the metropolis is one of our core goals.”