The notion of the Aussie backyard is dying, but don’t blame apartments

Population growth, cost increases and an outdated view of what the ‘Great Australian Dream’ looks like have killed the classic and beloved backyard.

Australia has spent decades building the wrong type of homes and the notion of the classic backyard is now dying as a result – but don’t blame higher density apartment living.

Instead, it’s the modern iteration of houses themselves that has seen the dream of a decent-sized patch of grass become increasingly unlikely to materialise.

Elek Pafka, a senior lecturer in urban planning and urban design at the University of Melbourne, agreed that the quintessential backyard is an endangered species.

But Dr Pafka said it’s not a new phenomenon.

MORE: Huge prediction for Aussie house prices

“It’s been dying for a few decades now,” he told news.com.au.

“The trend has long been to build bigger and bigger houses, while the lot sizes either remain the same or shrink. They’re left with very little green space, little vegetation, and little space between houses.”

It’s true that a mad scramble to address the country’s housing affordability crisis via massive increases to supply, currently underway in many parts of the country, will inevitably see fewer houses with backyards built.

But a greater focus on denser development in key parts of major cities isn’t the culprit, and on top of that, density is key to addressing exploding home values and soaring rent costs.

MORE: Countries that will pay Aussies $140k to move there

Since the onset of the Covid pandemic, home prices nationally have boomed by 38.1 per cent to $814,000, while prices across the capital cities have leapt 33.6 per cent to almost $900,000.

At the same time, tenants have been squeezed by rapid rental price hikes on the back of soaring demand and dwindling supply.

In the year to December 2024, the median weekly rent at a national level rose 4.8 per cent year-on-year, on top of an 8.1 per cent rise in 2023, and 9.5 per cent in the year before that.

Race for density across Australia

Authorities in the country’s two largest cities have grand plans to dramatically increase the proportion of dense developments, in a bid to house rapidly ballooning populations.

The New South Wales Government’s flagship housing supply policy will see planning changes to encourage transport-oriented developments within 400 metres of 37 train stations.

That will make way for an estimated 170,000 new dwellings – predominantly medium- and high-density apartments.

“Sydney needs, and can accommodate, more density in these locations, but it needs to be done well,” Committee for Sydney planning policy manager Estelle Grech said.

“Parks, schools, libraries, and public spaces are critical for ensuring these new neighbourhoods remain liveable and resilient for generations to come, and we hope they’ve been factored in.”

Similarly, the Victorian Government’s Suburban Rail Loop project will allocate density provisions around six new stations, resulting in some 70,000 new dwellings.

And other major centres across the country are also turning to greater density to manage soaring resident bases.

In Brisbane, Lord Mayor Adrian Schrinner warned in early 2023 that there was little space left for traditional housing estates, requiring new development to be contained within existing suburbs.

And in Adelaide, several new growth corridors along major transport routes have been identified, with authorities proposing increased density.

Houses still being built, but ….

Back in 2010, housing expert Tony Hall from Griffith University’s urban research program wrote the book ‘The Death of the Australian Backyard’.

He potted the drastic changes in home design that kicked off in the 1990s and sped up over the following years.

“Houses with large backyards ceased to be built,” Professor Hall wrote.

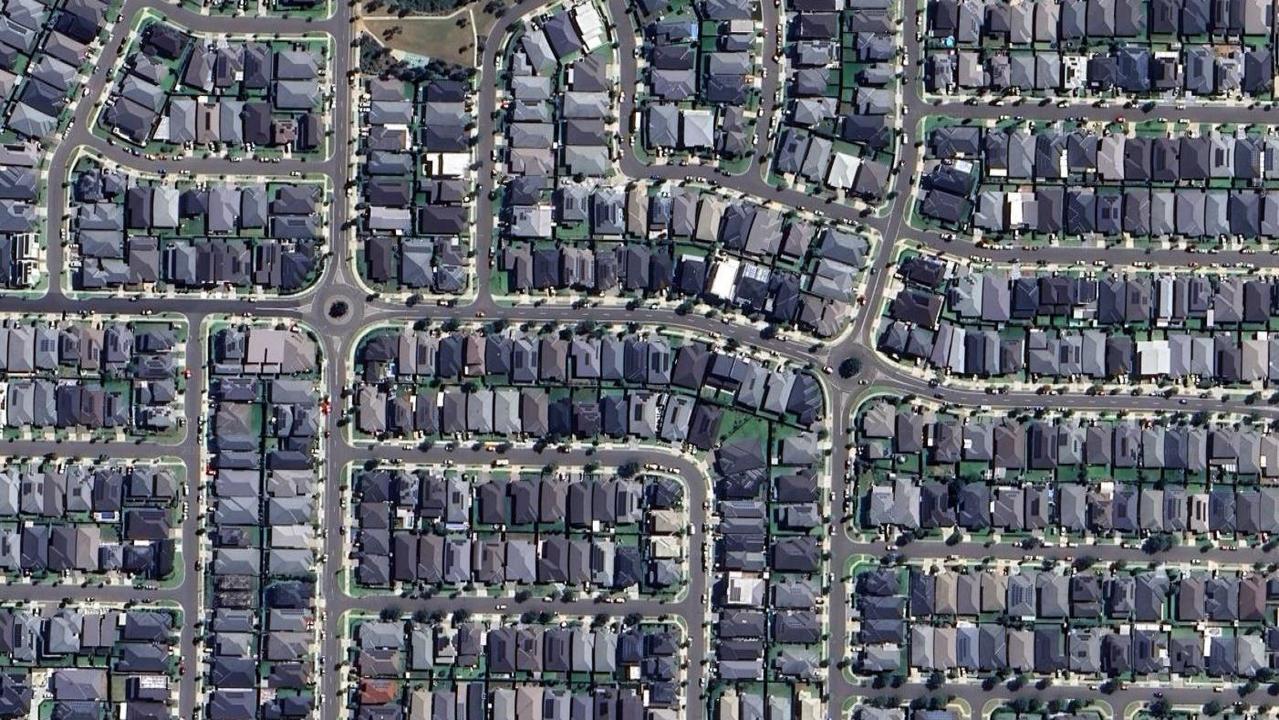

“Dwellings built since then now extend to within a few metres of the side and rear boundaries of the lot. This change has not been subtle or gradual in either space of time. It is a phenomenon that is immediately apparent from any aerial view.”

These dense suburbs filled with detached housing are on the fringes of major cities, where urban sprawl has run uncontrolled for many years now.

When pundits mourn the upcoming death of the backyard, these are the types of properties they’re talking about.

“The backyard that has grass for the kids to play on, a vegetable garden, a nice big tree – those are already gone in many ways,” Dr Pafka said.

According to the 2021 Census, some 53 per cent of homes in Greater Sydney were stand-alone dwellings – or houses – while 27 per cent were high-density apartments and another 18.8 per cent were medium-density properties, including units and townhouses.

Recent projections on how those proportions might shift over time are hard to come by, with dwelling supply forecasts tending to focus on total volume rather than property type.

In addition, the residential construction sector has been in the midst of chaos for the past several years, with historically low levels of dwelling approvals and construction starts.

Modelling the future mix of dwellings is challenging as a result.

That said, the bulk of various new housing targets around the country are made up of medium- and high-density apartments.

Density’s big stumbling block

Those concerned about the impacts of denser cities, alongside Australians mourning the inevitable loss of the good-old backyard, don’t need to panic imminently.

CoreLogic economist Kaitlyn Ezzy said building commencements have trended lower in recent times, with the figure for the year to June 2024 hitting a decade low.

On top of that, dwelling approvals over the year to November 2024 were 7.1 per cent below the 10-year average.

“These factors combined have contributed to an increasing number of liquidations, with 2,832 construction companies becoming insolvent in the 2023-2024 Financial Year, representing the greatest proportion of company collapses.”

According to the Urban Taskforce, the data on dwelling approvals shows there’s a “mountain to climb” when it comes to new apartment supply.

The figures expose a “chaotic trend” in the wrong direction despite state and federal initiatives to boost development.

In the year to November, the total number of dwellings approved in NSW was 42,109 – a whopping 34,000 fewer than required to meet the state’s National Housing Accord quota.

Drilling into the numbers, Tom Forrest, the group’s chief executive, said development activity within the State Government’s 37 TOD precincts has been “extremely disappointing”.

“Comparing states, we see NSW’s continued downtrend against Victoria and Queensland, which maintain a more stable trend, closer to their targets and a higher dwelling approvals per capita rate than NSW,” Mr Forrest said.

Must do density well

While density is a crucial part of efforts to tackle Australia’s housing affordability crisis, it needs to be done well to prevent the continued construction of inappropriate dwellings.

“It’s not that we should abandon building suburb houses and that we should only build apartments in very dense high-rises,” Dr Pafka said. “We should cater to all different desires that people have.”

And there’s clearly a demand for density – but in the mid-range, he said.

That could be smaller complexes of five to seven storeys, comprising a variety of unit sizes, including larger floorplans for families.

And it should feature lots of communal spaces and convenient access to parks and playgrounds.

“With that kind of density we could build mixed-use neighbourhoods that are less reliant on cars, meaning there’s less traffic, and with access to shared green spaces,” Dr Pafka said.

Planning authorities have got it wrong a lot in recent times, approving high-density development with minimal green space and a lack of crucial infrastructure and amenities.

In response, a pair of academics created the Recreational Activity Benchmark – a model analysing a new population’s needs based on projected demographics.

“To meet this benchmark level of recreation demand in the limited space available requires a mix of strategies,” Anthony Veal from the University of Technology Sydney and Awais Piracha from Western Sydney University explained in a piece for The Conversation.

“The first strategy is to rely more on indoor facilities such as sports halls, gyms and swimming pools. These allow for high levels of physical activity using much less land than traditional playing fields.”

Those types of indoor facilities can open longer, can be built as part of high-density and multipurpose developments, and aren’t affected by bad weather.

“The second strategy is repurposing non-traditional open spaces for recreation. In particular, designing streets, footpaths and pavements as pleasant green areas encourages walking and cycling. Maintaining these areas for such activities thus also provides for recreation.”

For example, schoolyards and rooftops could be transformed in active recreation spaces, with the researchers pointing out examples from abroad.

In Singapore, the successful Dual Use scheme sees school playgrounds and sporting fields opened to the public after hours.

Meanwhile, in South Korea’s capital Seoul, an old highway overpass that was no longer needed was transformed into a spectacular kilometre-long walkway, green space and public recreation zone.