‘We are governed by mongrels’: Driver of housing crisis revealed

A top economist has slammed “mongrel” governments for causing the crippling housing crisis that’s leaving millions of Aussies struggling.

Governments have manufactured a crippling crisis that’s led to unprecedented housing pressures, a rising risk of homelessness, and the rapid death of the Great Australian Dream.

And while Anthony Albanese champions multibillion-dollar plans to build more homes and save families from financial disaster, the Prime Minister has avoided mentioning one key driver.

Immigration.

By June, an estimated 885,000 new migrants will have arrived in Australia in just two years, at a time when a critical undersupply of housing is pushing purchase prices and rents to new highs.

Leith van Onselen, co-founder of MacroBusiness and chief economist at MB Fund and MB Super, said the decision to “funnel in record amounts of people … is arguably the biggest driver of the housing crisis”.

Mr van Onselen said the pursuit of “extreme” population growth to drive the economy shows Australia is “governed by mongrels”.

“Federal governments have massively increased immigration since the mid-2000s, and that’s basically created a structural housing shortage,” he said.

“Now it’s worse than ever, with the largest number of migrants ever coming to Australia, resulting in mammoth population growth.

“There are way more people coming into the country than we can build houses for, and we’re feeling the pressure of that across the market.

“All the while, it takes you longer to drive anywhere, you can’t find a place to live, you’re spending your weekends at inspections with hundreds of other people, and if you find a place, your landlord will probably hike your rent $100 a week or so.

“This is what we’ve done. It’s madness.”

Brendan Coates is the economic policy program director at think tank The Grattan Institute and said the record migrant intake is “clearly a driver of pressure in the rental market”.

“We estimate that every 100,000 additional migrants above the long-term trend probably adds about one per cent to rental costs,” Mr Coates said.

“So certainly, the surge that we saw over the course of the last financial year through to June 2023, that’s probably adding three to four per cent to rent prices.

“Given that rents rose by 7.8 per cent over the course of last year, it’s a big driver.”

People are furious

This week, news.com.au’s exclusive sit-down interview with New South Wales Premier Chris Minns, dissecting his government’s proposed solutions to the housing crisis, sparked fierce debate online.

Scores of commenters attacked record high immigration as the cause of affordability pressures, particularly in the rental market, and called for action.

“It’s no wonder there is seemingly a growing resentment towards migration,” PropTrack executive director of research Cameron Kusher said.

“When you consider those that are already here in Australia are paying high prices for shelter or struggling to even find shelter for themselves.”

Social services groups say the skyrocketing cost of rent is forcing an alarming number of households into financial distress and increasing the risk of homelessness.

Currently, the national rental vacancy rate – that is, the proportion of all leased dwellings available on the market – is about one per cent.

Migration provides big benefits to Australia by helping to grow the economy, but Mr Kusher said it also creates huge demand for housing and infrastructure.

“And not enough is being done to address the deficit of either, notwithstanding the huge amount of infrastructure investment taking place in Sydney currently,” he said.

“Given this, a growing number of people feel as if their quality of life is deteriorating and that the more people that come to the country, the more it will deteriorate because this deficit of housing and infrastructure is not being addressed.”

Those in positions of power who ignore the concerns of voters and fail to act run the risk of suffering politically, he said.

“If governments shy away from reforms that allow more housing supply, improve productivity and just generally improve people’s quality of life, I anticipate there will be an increase in protest votes and votes shifting from major political parties to smaller parties.”

The mammoth increase in migration was “so sharp and so fast” that the pressure placed in housing markets must be addressed, Mr Coates said.

“If we don’t get housing right, then we’re of throwing low-income renters under the bus, and I don’t think that’s a sustainable position.”

Bursting at the seams

The significant role immigration is playing in the housing crisis shouldn’t have come as a surprise to policymakers, Mr Kusher said.

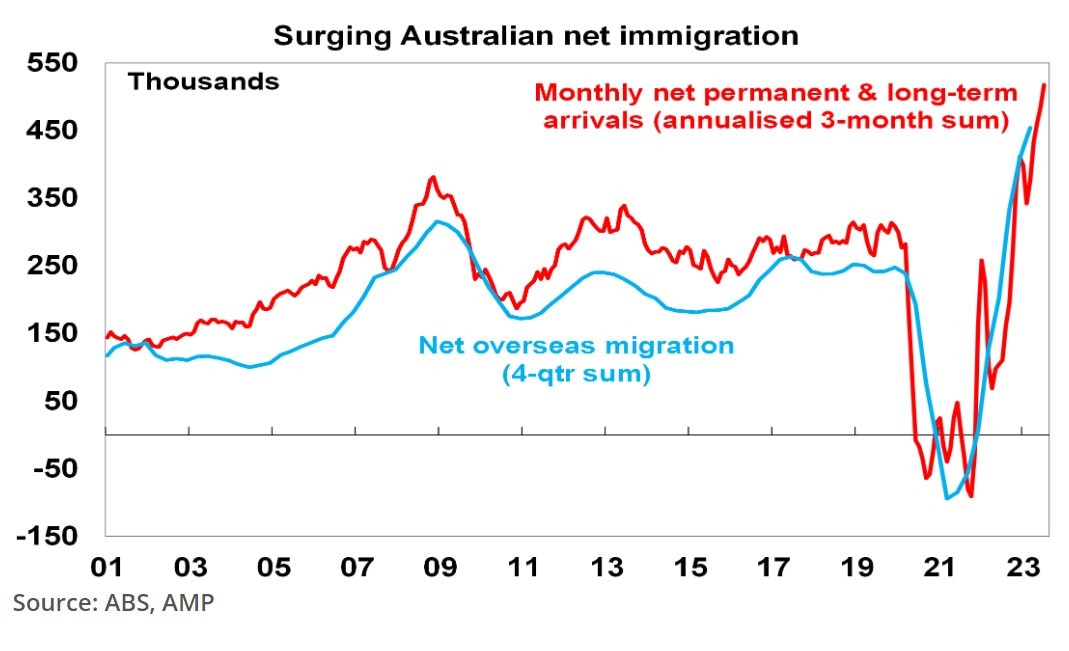

In the 12 months to June 2023, the net migration level in Australia was 510,000 and another 375,000 will be added to the tally by the middle of the year.

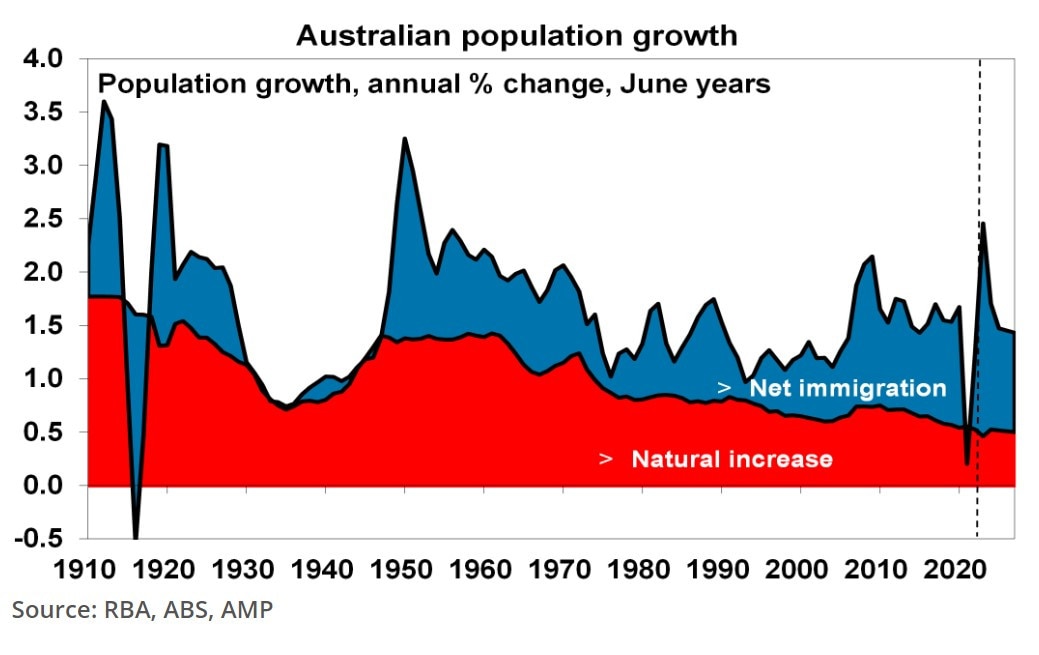

That record level of immigration sparked the largest percentage increase in our overall population in more than 70 years.

“Housing construction was already slowing, and rental vacancy rates were already extremely low so little if any consideration was given to where these migrants were going to be housed,” Mr Kusher said.

“As a result, it has tightened supply further, created more competition and lifted rents by a significant amount.”

Big increases in the number of people coming to Australia aren’t a new phenomenon, with the average net migration rate in the decade before Covid sitting much higher than the 10-year period preceding it.

At the turn of the century, Melbourne’s population sat at about 3.4 million people, while these days it’s hovering around 5.07 million.

Likewise, some four million people lived in Sydney back in 2000, while the city is now home to a whopping 5.31 million residents.

“That’s incredibly fast growth in a very short period of time,” Mr van Onselen said. “And the vast majority of that growth is immigration.”

Experts say the impact on housing markets of 885,000 more people, in the midst of a supply crisis, can’t be overstated.

Building sector can’t keep up

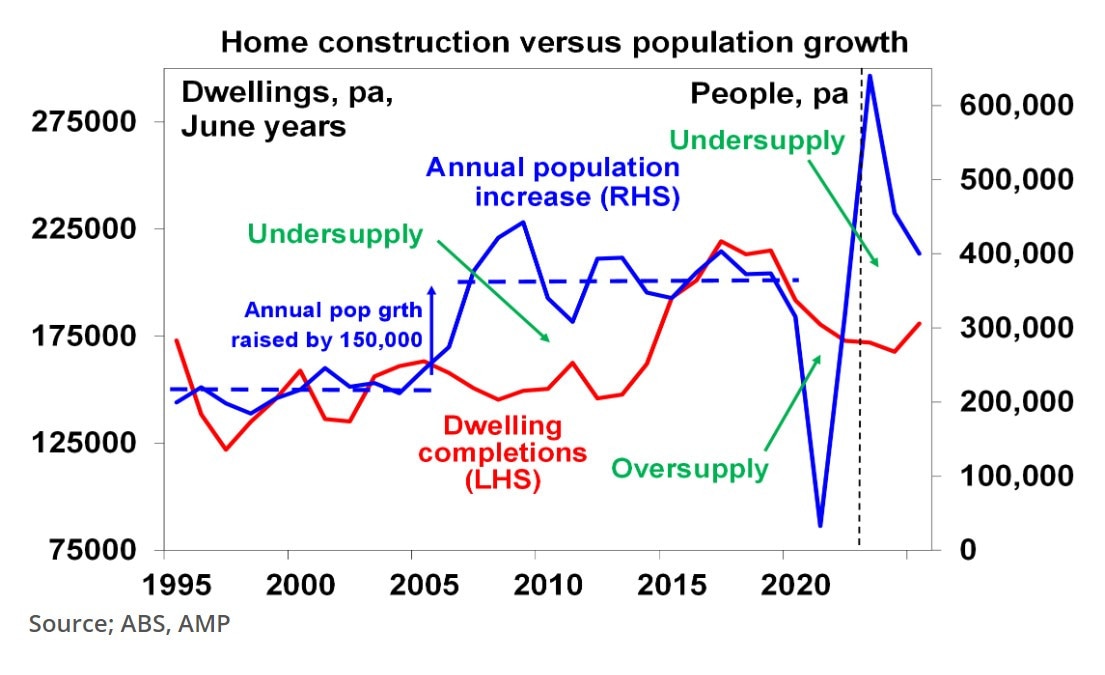

The surge in immigration saw underlying demand for housing pushed up to an eye-watering level of 220,000 new dwellings per year, according to AMP chief economist and head of investment strategy Shane Oliver.

“But thanks to rate hikes and capacity constraints, dwelling completions look like averaging around 175,000, which means a new shortfall each year of about 45,000 dwellings adding to the already existing shortfall,” Dr Oliver said.

A number of things need to be done to improve housing affordability, he said, like building more homes in the right places and taxation reform.

“But it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that immigration levels need to be calibrated to the ability of the home building industry to supply housing. This is critical,” Dr Oliver said.

The level of immigration being seen currently is “running well in excess” of the ability for construction sector to build enough new homes.

Even if Australia managed to build 200,000 new homes a year, immigration levels would still need to be slashed to almost half what they have been, he said.

“Over the last decade, home building did not keep pace with increases in demand, and prices rose,” a report from the Grattan Institute in 2018 noted.

“Through the 1990s, Australian cities built about 800 new homes for every extra 1000 people. They built half as many over the past eight years.

“We estimate somewhere between 450 and 550 more new homes are needed for each 1000 new residents, after accounting for demolitions.

“And because more families are breaking up and the population is ageing, more homes are needed to accommodate households with fewer members.”

Economy needs migrants

For the past two decades, population growth has been a crucial driver of Australia’s economic growth – and the vast majority of the increasing resident base is thanks to immigration.

A strong and diverse economy is crucial in countering an ageing population and reduced productivity, economists say.

“We can slow migration, and there are some things we definitely should do, and while big cuts to the migration program would certainly make housing more affordable, they would probably make us poorer as well,” Mr Coates said.

“Skilled migrants contribute much more in taxes than they (use) in services, so they provide a really big boost to the federal budget.

“If you cut 10,000 places in that program, it would cost federal and state government budgets between $68 billion and $125 billion over the next 30 years.”

The pandemic saw migration screech to a halt – and even a hit a net negative figure in 2021 due to border closures and a pre-planned reduction in overall numbers.

In analysis for The Conversation, University of Sydney public policy and political science academic Anna Boucher and Professor Robert Breunig from the Crawford School of Public Policy at Australian National University, said “immigration is vital to the economy”.

“Immigration growth drives economic growth,” they wrote.

“Lower immigration has a real effect on GDP. In the June quarter of 2020, GDP contracted by 7 per cent, which is the largest fall on record. At least some of this is due to plummeting immigration.”

In addition, international student migration and tourism form a large part of Australia’s vital exports, while skilled migrants help plug critical labour shortages in key industries like construction and agriculture.

“Fewer immigrants result in fewer people of working age contributing to the tax base,” they added.

“Many immigrants are generally under 45 and are here to work — either in skilled jobs or on working holiday visas. Losing large numbers of them means fewer people of working age in the population.”

And lower immigration rates affect levels of consumption, with “less demand for services and housing”.

Mr Kusher believes the short and medium-term benefits of migration right now don’t outweigh the consequences.

“Many will argue that migration brings with it many benefits, which I also believe to be the case,” he said.

“But when housing costs are high, the cost of goods and services is rising rapidly, and people feel like their quality of life is going backwards, many appear to be questioning the wisdom of importing so many people from overseas, especially given there hasn’t been a commensurate rebound in new housing supply.”

Are changes too late?

The current situation isn’t all the fault of the Albanese Government, which inherited a situation that was difficult to reverse.

“But there have been some decisions Albanese has made that have made the migration flows bigger,” Mr Coates said.

“He’s increased the size of the permanent intake by 30,000 a year, he’s granted New Zealand citizens the greater rights to stay permanently in Australia, and he’s certainly accelerated visa processing.”

And while immigration plays a big part in the housing crisis, it’s not the sole driver of dwindling supply, Mr Coates pointed out.

There has been a change in how many Australians are choosing to live since Covid, with the rise of working from home seeing some choose larger homes, and a shrinking in the size of households, he said.

“Immigration is probably not the biggest driver of rising rents right now. It’s probably the second biggest after the fact Australians are demanding more housing.”

The Federal Government has responded to concern and criticism by announcing in December that it would bring migration “back to normal levels”.

But Australian Catholic University research fellow Rachel Stevens said the cuts were “not as dramatic as they seem”.

“The government says these changes are the ‘biggest reforms in a generation’ (that) will ‘dramatically cut’ the immigration intake, but don’t be fooled by the hyperbole,” Dr Stevens wrote in analysis for The Conversation.

“The intake cuts are overstated and will largely be the result of a natural evening out of migration patterns in the post-pandemic world.

“Even the Department of Immigration acknowledges the spike in arrivals is ‘temporary’, a phenomenon labelled as ‘the catch-up effect’ by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.”

Right now, an estimated two million foreign nationals are in Australia on temporary resident visa, comprising mostly skilled workers from New Zealand, international students, and recent graduates.

The Albanese Government has committed to finding pathways for skilled migrants to become permanent residents.

Temporary visa numbers have been uncapped since John Howard was prime minister and the number of foreigners here for short and midterm tenures has doubled in the past 15 years.

Even with immigration reducing in coming years from its post-Covid record highs, Mr van Onselen projects it will remain above the long-term trend.