‘It doesn’t have a future': The plan to save Sydney from itself

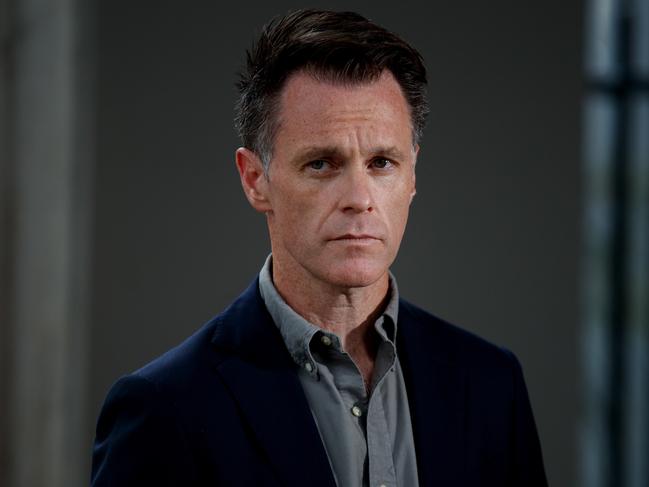

NSW Premier Chris Minns warns Sydney has “no future” unless an alarming trend is reversed – and he has a plan to save the city from a mass exodus.

Sydney has a major problem.

Australia’s largest city, once a vibrant and exciting place to live that ranked on par with global icons like New York and London, is haemorrhaging young people.

A major driver is the skyrocketing cost of housing, where it’s not even homeownership that upcoming generations worry if they’ll ever be able to afford – but rent.

“There’s a funny thing about Sydney,” NSW Premier Chris Minns told news.com.au in an exclusive sit-down interview.

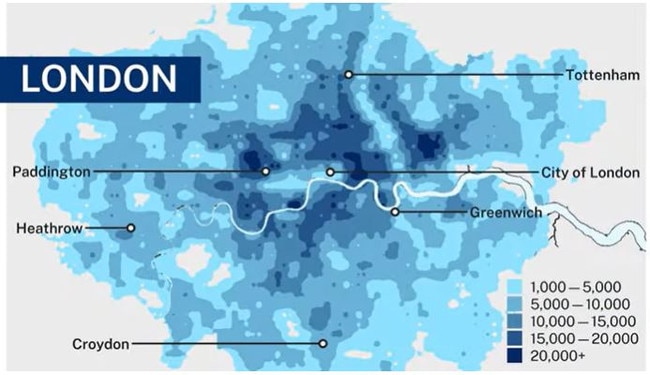

“We’re about the 830th densest city in the world and yet by most measures, we’re in the top five or the top 10 when it comes to being the most expensive. Those two things are related.”

The median house price in the Harbour City hit $1.34 million in February while the median unit price sat at $793,000, according to the PropTrack Home Price Index.

Those eye-watering sums have soared by 8.23 per cent and 6.16 per cent respectively over the past 12 months.

Meanwhile, the median weekly house rent is $1049, up 12.2 per cent year-on-year, and the median unit rent is $701 per week, up 10.5 per cent in the past 12 months, SQM Research data shows.

“I can imagine it’s really difficult, particularly for young couples,” Mr Minns said.

“It used to be the case that people would say, when I was young, ‘Oh, will I ever be able to afford to buy a place in Sydney?’ And now a lot of people say, ‘Will I even be able to afford to rent a place?’ The cost of housing has exponentially grown.”

Mass exodus of young people

Last month, a stark report from the NSW Productivity Commission warned that Sydney lost twice as many young people than it gained in a five-year period.

According to the data, about 35,000 people aged 30 to 40 moved to Sydney between 2016 and 2021, – but an estimated 70,000 fled.

Productivity Commissioner Peter Achterstraat said the city is at risk of becoming “the city with no grandchildren”.

“Sydney is losing its 30- to 40-year-olds,” Mr Achterstraat said, adding authorities need to act now.

“Many young families are leaving Sydney because they can’t afford to buy a home, or they can only afford one in the outer suburbs with a long commute.”

Mr Minns also blamed the enormous cost of keeping a roof over one’s head for “many just up and leaving” over recent years, and warned the cost of the mass exodus will be severe.

“If you’ve got so many young people up and leaving, then they’re not joining communities, starting businesses, going to the pub with their mates, and when they get a little bit older, becoming the coach of the football team.”

It’s not just grandchildren the city is at risk of losing, but its once-vibrant nature, Mr Minns said.

“The measure of a city’s vibrancy is how many young people are part of it. If you can get young people part of a city, then they will open clubs, start businesses, and think about creative and fun ways of re-imagining the city.”

In December, the premier unveiled his strategy to tackle the problem and save Sydney from itself and warned “the city doesn’t have a future unless we make these changes”.

It hasn’t been well-received in certain sections of the community, including among several Labor-controlled councils in key areas.

Controversial plan to correct course

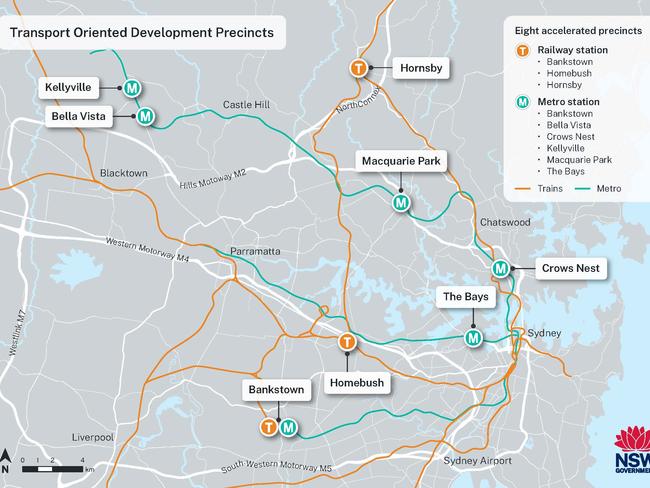

The State Government’s strategy is three-pronged – the first being a transport-oriented development (TOD) program.

It has identified eight transport hubs, dubbed Tier One sites, where accelerated rezoning could help deliver up to 47,800 new homes over the coming 15 years.

By the end of the year, changes to planning permissions will allow more density in developments location within 1.2km of metro or train stations at Bankstown, Bays West, Bella Vista, Crows Nest, Homebush, Hornsby, Kellyville, and Macquarie Park.

Fifteen per cent of dwellings in approved developments must be affordable and available to key workers, like nurses, teachers and hospitality professionals, and construction must start within two years.

But Mr Minns said there will be broader benefits from increased supply for countless renters and hopeful first-home buyers.

In addition, 31 other locations across the state will be ‘snap rezoned’ to allow greater densities within 400m of metro of suburban rail stops and town centres.

The idea is to create new homes in locations that have existing infrastructure, such as Ashfield, Dulwich Hill, North Strathfield, North Wollongong, and Gosford.

The second component of the government’s plan is to allow different types of homes in identified suburbs, like flats, terraces and duplexes.

Each council currently has its own rules on what types of dwellings are permissible in their areas, and most don’t allow those types of buildings.

“If a council doesn’t change its rules, then the State Government’s rules will … apply, to confront the housing crisis,” a Department of Planning and Public Spaces briefing note reads.

A ‘pattern book’ containing pre-approved designs for those housing types will also fast-track development.

The third prong sees $520 million commitments for community infrastructure projects in Tier One locations to support the extra density, such as public open spaces and road upgrades.

Mr Minns described the sweeping reforms as “modest” given what’s at stake.

“We can have a modest change to the amount of people or houses that we build each year, and over time it can make a massive difference to the cost of housing,” he said.

At least two Labor councils have expressed opposition to the plan, arguing it could reduce living standards for residents by oversimplifying the current rules.

Inner West Council and Canterbury Bankstown Council took aim at the premier, saying the reforms will have “major implications” for their residents and hinted a legal challenge could be launched.

Fairfield Mayor Frank Carbone told The Sydney Morning Herald that Mr Minns would turn “western Sydney into Kolkata” – the Indian city of 14.8 million people – and mark “the end of the backyard”.

“This is not an attempt to demolish Sydney and start again,” Mr Minns said. “These are pretty modest in the scheme of things.

“A little bit more will go a long, long way. Not doing anything is not a solution. Cities that don’t do that lose their vibrancy, their character. Ironically enough, you do change the city by not changing it all.”

Mr Minns said he wasn’t elected “to be popular” or make decisions for political capital.

He’s hopeful he can “get people on the fence to say, ‘You know what, something needs to change, it’s not going to destroy the city, I can sign up to that.’”

And he issued a call to arms to young people across the state, declaring that “we’re in this for them”.

“We want them to claim their bit of this great city because that was what was given to their parents and their parents’ parents and the generation prior to that.

“We don’t want young people in NSW to be the first generation to miss out on their bit of Sydney.”

Sydney’s missing 45,000 homes

The cost of doing nothing was made abundantly clear in the Productivity Commission’s report.

Some 45,000 extra dwellings could’ve reasonably been built over the five years from 2017 to 2022 with no extra land required, by allowing higher buildings in key areas, Mr Achterstraat said.

“This could have seen prices and rents 5.5 per cent lower – $35 a week for the median apartment, or a saving of $1800 a year for renters.”

In 2023, NSW built 48,000 new dwellings across the state, producing about six homes for every 1000 people.

That pales in comparison to the 59,000 completions in Victoria, equating to eight homes per 1000 residents, and the state even came in behind Queensland.

He advocated “building up” in Sydney’s inner-suburbs – not just on the fringes – which would boost productivity and wages, cut carbon emissions, and preserve land and green spaces.

“Sydney needs hundreds of thousands of new homes over the next two decades. Building more in the places people want to live is a key piece to solving the housing jigsaw puzzle.”

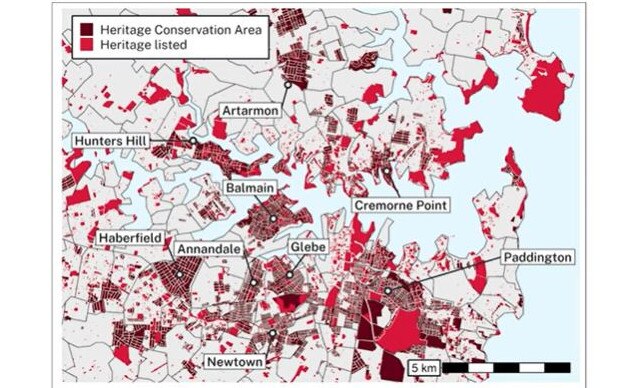

And he too insisted density can happen without sacrificing the historic charm in suburbs earmarked for higher density, such as Balmain.

“We can preserve the gems of Sydney’s heritage without inadvertently freezing young people out.”

Read related topics:Sydney