Mortgages could rise by $600 a month due to heated inflation

In nine months, millions of Aussies could need to find at least $600 extra a month – and that’s on top of rising food and petrol costs.

Feeling tempted to buy a house after the budget? That is understandable. The budget was packed with goodies.

There were cash handouts, like the $250 for cost of living.

There were petrol discounts. They could be worth $700 to a two-car family in the next six months.

There were reduced tax bills too: most people will be $420 better off at tax time this year.

That all adds up to Aussies feeling a touch wealthier than before the budget.

Meanwhile the government has added 50,000 new places to the Home Guarantee Scheme, which means you can buy a house with a smaller deposit. Plus Prime Minister Scott Morrison says he wants to help renters buy.

“Ensuring that more renters can buy their own home and get the security of home ownership, this is one of the key focuses of this budget,” said Mr Morrison on Wednesday.

So it looks like a time to buy. Right?

Enter at your own risk

Please, please. Be cautious.

Because while one part of government gives, the other takes away. This budget is also likely to unleash a wave of interest rate rises.

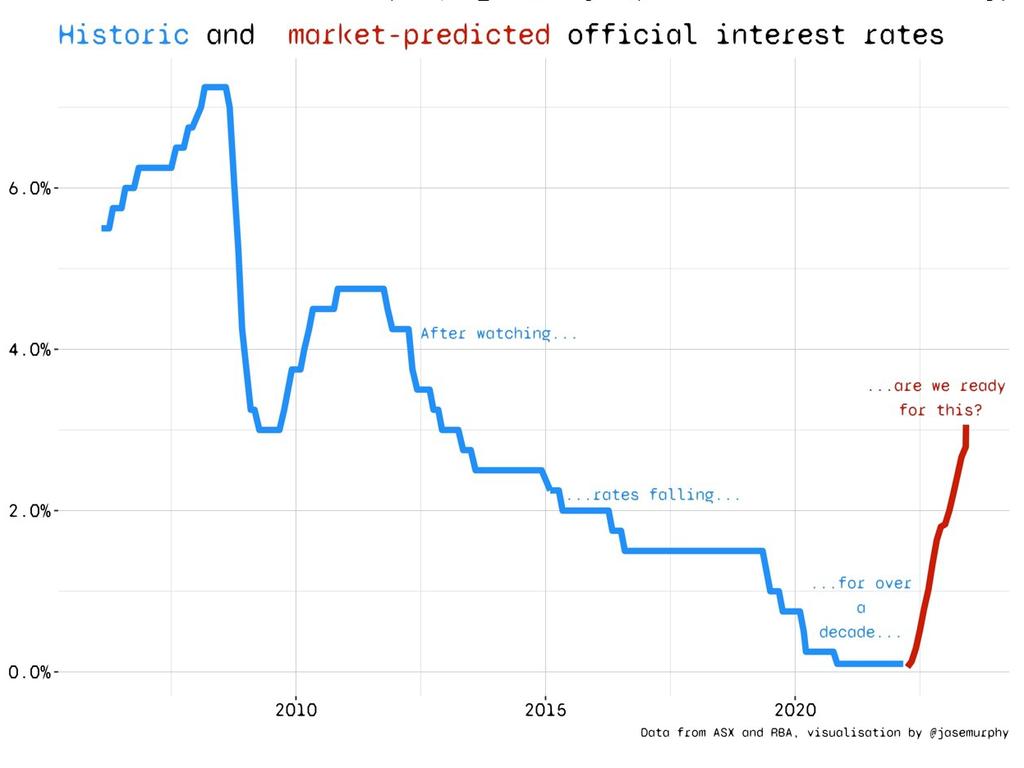

The RBA could deliver an interest rate hike in June, and then at least six more by the end of the year, according to market expectations. As the red line in this next graph shows, the future of interest rates is up, up, up.

What will that cost?

The average new home loan for an owner-occupier these days is a bit over $600,000. Repayments on that loan are around $2350 a month at the average mortgage rate (2.48 per cent). If interest rates go up seven times by December, repayments would be $2,950 a month. That’s an extra $600. Can you find that much extra in just nine months?

Remember you’ll need that extra money just when the petrol excise cut expires and fuel prices go back up by 22 cents a litre. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg talked non-stop on budget night about how cutting excise will help families now. He was silent about the sting in six months when the fuel price cut comes to a sudden end.

Take a hike

Have no doubt the banks would pass on interest rate rises in full. In fact, they’ve been lifting some mortgage interest rates before that even happens.

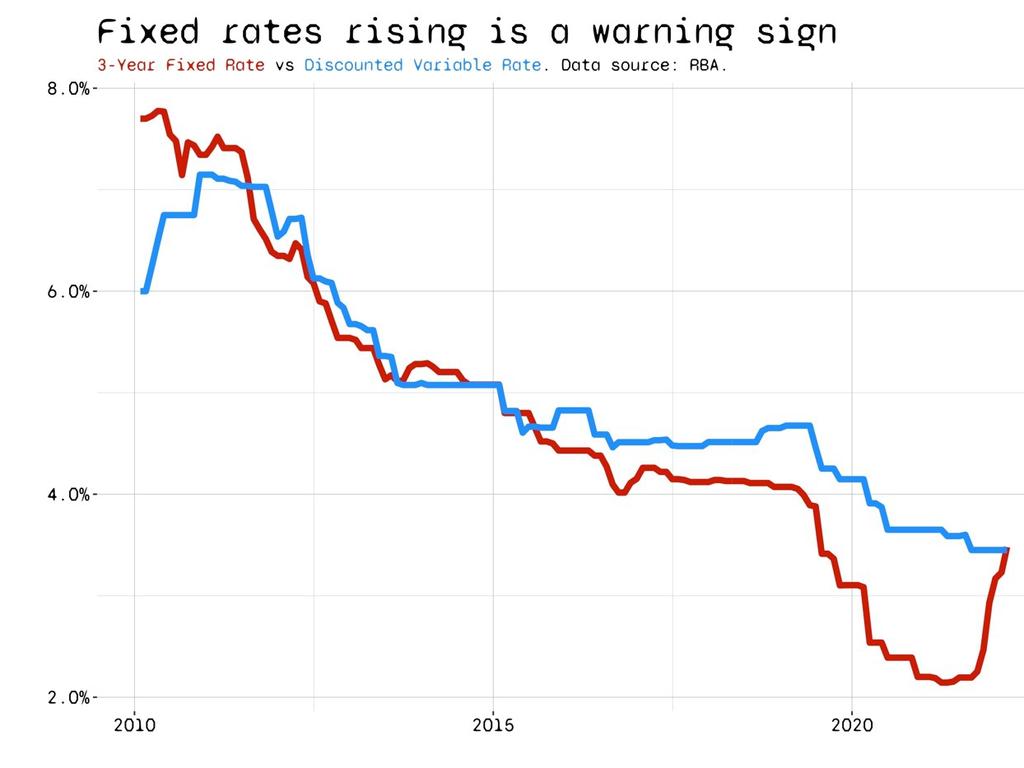

Take a look at fixed interest rates. Recently they were below variable interest rates, as the next graph shows.

Banks thought they would benefit from locking your rate in. Now, fixed rates have shot up as banks realise locking people into a low rate was good for the customer, not for them. Rising fixed rates are a sign banks don’t want to lock people into a low rate; a sign banks think official interest rates will be rising soon, and variable rates will pop up too.

Home sweet home

Wanting to buy a house now is understandable: rents are rising and sometimes the time is right for your family. If you see a house you love with all your heart, the financing might not matter.

But anybody who gets into the housing market now should have full awareness of house price forecasts. The nation’s biggest lender, Commonwealth Bank, forecasts this will happen: “house prices nationally to be flat in 2022 and down 8 per cent in 2023,” they said this week.

If they are right – and it’s a big if ! – you might be able to get the same place for 8 per cent less money in 2023. You might be able to buy a $500,000 house for $460,000 in 2023 and save $40,000. Not a bad amount of money to have in your pocket.

Is the budget to blame for this?

Interest rates are at zero. Everyone expected them to go up. So you may be wondering why I’m saying the budget is (partly) to blame for interest rate rises. Here’s why: At the start of March, markets expected four or five interest rate rises by the end of the year, not seven. But as the details of the budget leaked, expectations pointed to more and more interest rate rises.

The reason is simple: the RBA uses interest rate rises to cool down inflation. But the budget is heating up inflation. So if interest rates do actually rise we can blame the budget for it, in part at least.

This is a key point for understanding the economy. If you give people lots and lots of money, prices tend to go up. It’s like at the end of a game of Monopoly when you sell Park Lane to your little brother for $2000 in Monopoly money – the number of properties in the game hasn’t gone up but the amount of money circulating has gone up, so prices rise. The RBA’s job is to stop prices from rising too fast and it does that by effectively taking money back out the game with interest rate rises.

The budget makes their job more urgent, because Josh Frydenberg has opened up the Community Chest and given out lots of cash.

In 2022, anyone looking to buy a house must look beyond their cash in hand and make sure they’re able to handle a world of much higher interest rates.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.