Variable mortgages and high debts leave Australians vulnerable to rate hikes

Australians are more vulnerable to interest rates rises than most other nations - and there are two scary reasons why.

It is Groundhog Day for Australia’s battle-weary mortgage holders, with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) hiking the official cash rate (OCR) another 0.25 per cent on Tuesday – the sixth consecutive monthly increase.

The good news was that it was a normal 0.25 per cent increase, not a 0.5 per cent ‘double’ experienced over the prior four months.

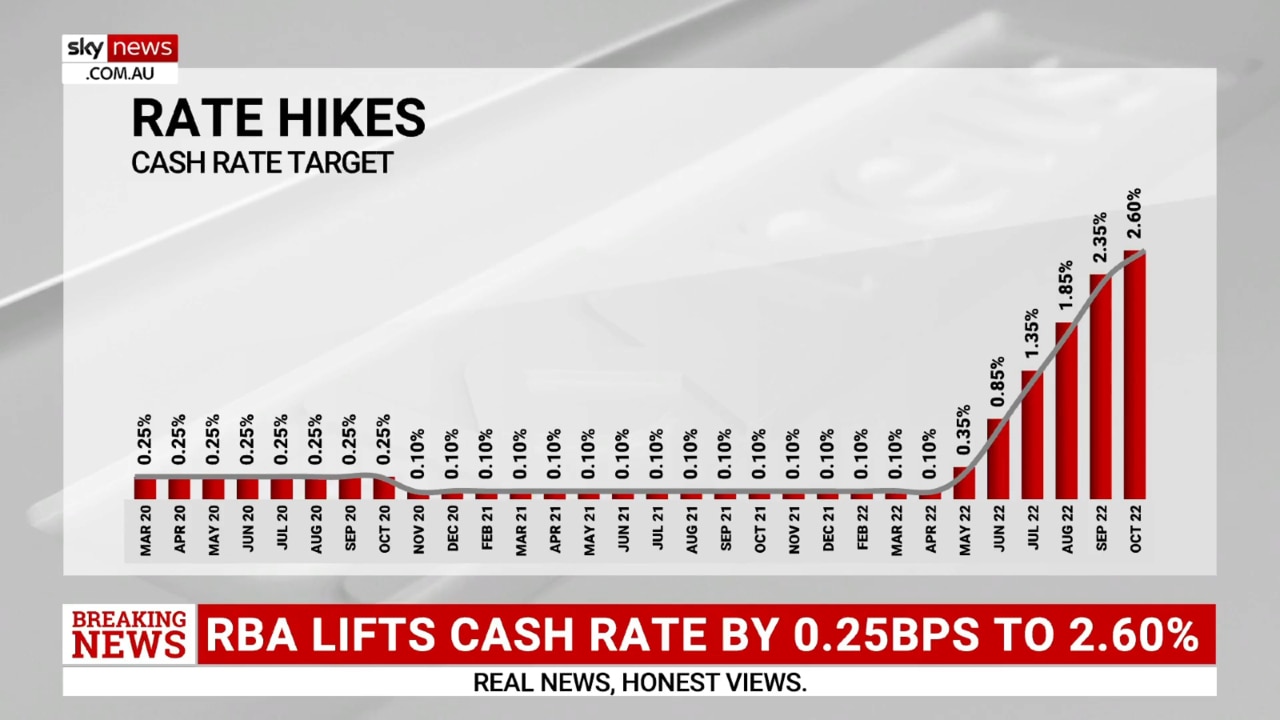

The increase has sent the OCR to 2.6 per cent, which is the highest level since July 2013. Once the increase is passed onto mortgage holders, Australia’s average discount variable mortgage rate will climb to 5.95 per cent, which will be the highest level since September 2012:

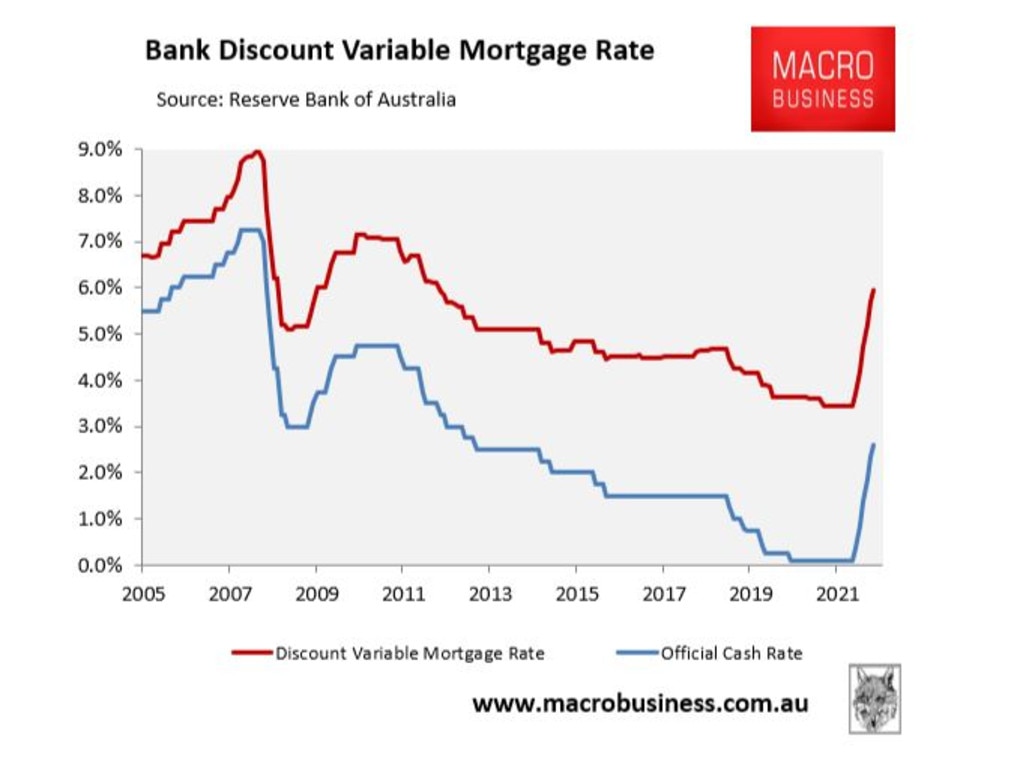

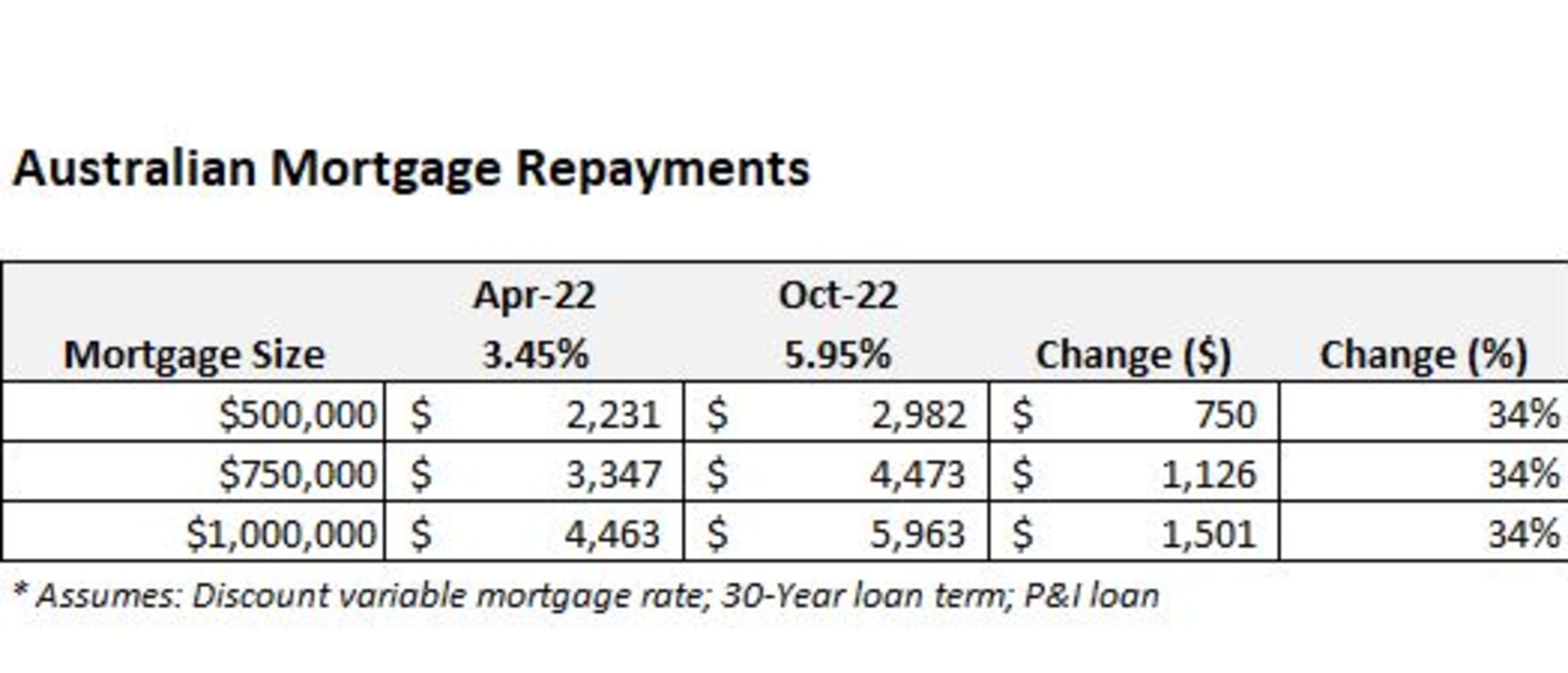

The overwhelming majority of Australian mortgage holders are on variable rates, and they are experiencing the sharpest increase in monthly mortgage repayments on record.

As illustrated in the next table, Tuesday’s OCR increase will lift average monthly mortgage repayments by 34 per cent above their level in April before the RBA’s first hike. For a borrower with a $500,000 mortgage, this will represent an $750 increase in monthly mortgage repayments.

A double blow for mortgage holders

The rapid increase in mortgage rates has driven a sharp decline in house prices.

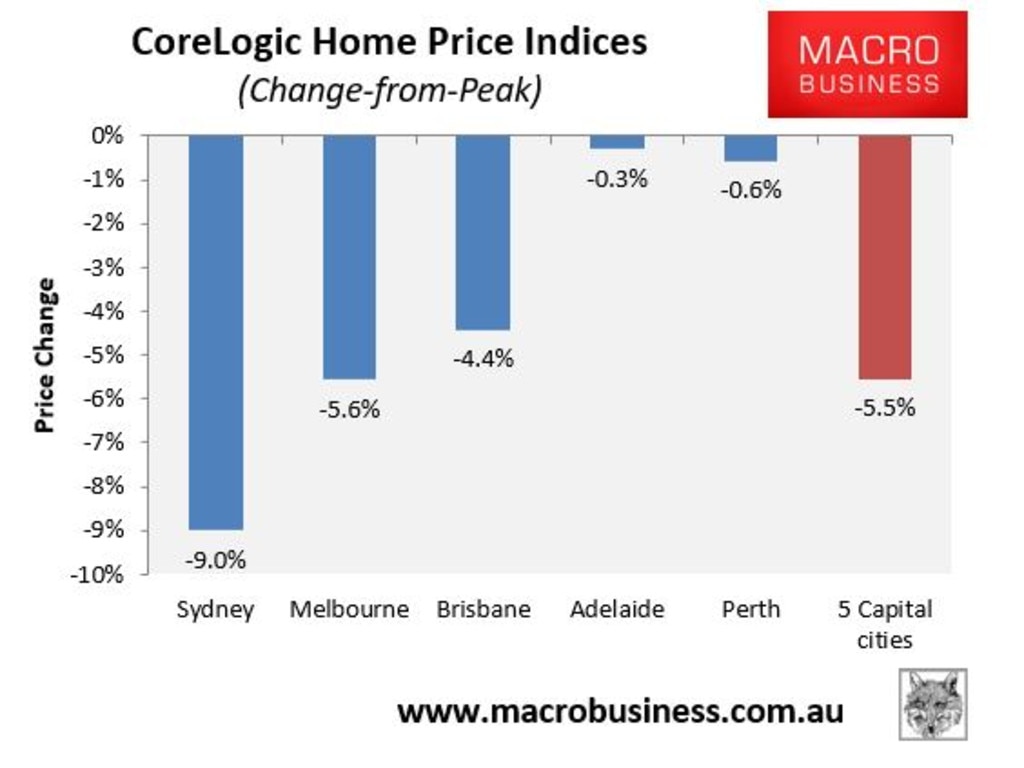

According to CoreLogic’s dwelling values index, Australian home values plunged another 1.4 per cent in August to be down 5.5 per cent from their most recent peak across the combined capital cities.

The ‘big three’ capital cities of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane are leading the correction, with Perth and Adelaide only recently joining the downturn:

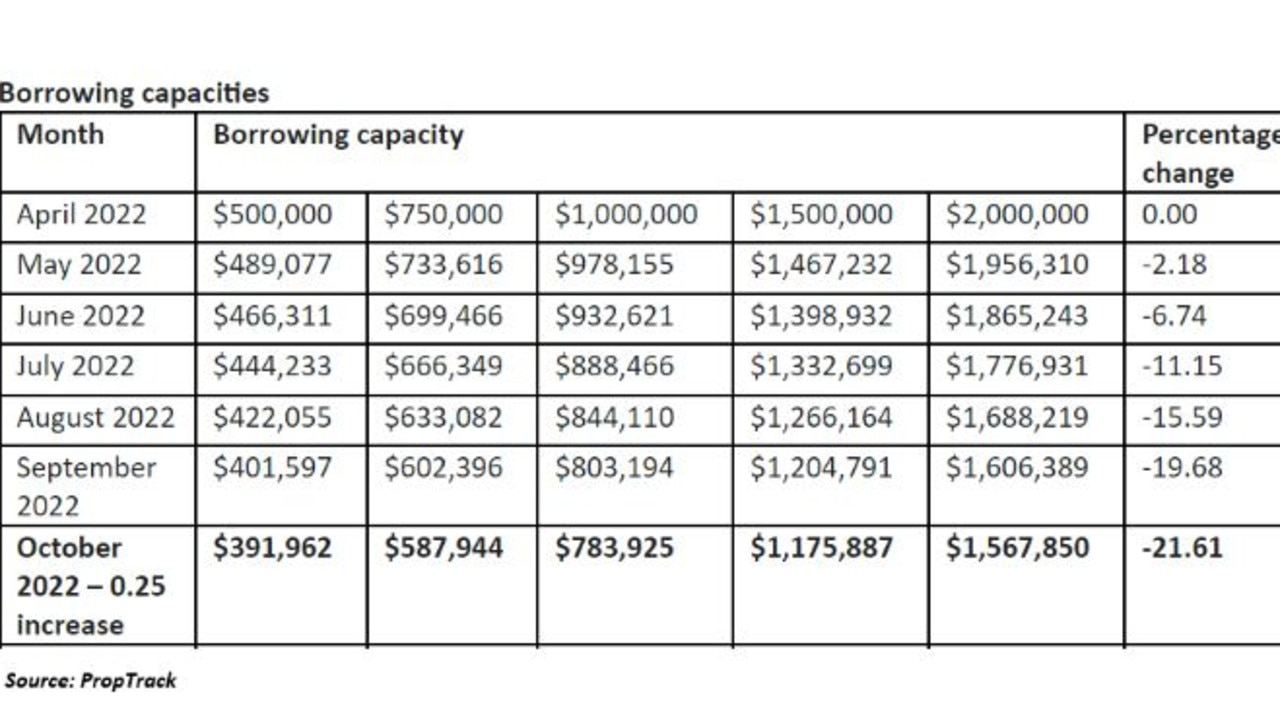

The latest OCR increase from the RBA will perpetuate the house price correction by further limiting borrowing capacity and shrinking the amount prospective home buyers can pay.

According to PropTrack, a prospective home buyer will be able to borrow 21.6 per cent less after Tuesday’s 0.25 per cent OCR increase. So, if a household was permitted to borrow $500,000 in April before the RBA’s first rate hike, they will now only be able to borrow around $392,000.

Sharply rising mortgage repayments and falling house prices will be a bitter pill to swallow for home buyers that borrowed large sums to enter the market over the pandemic under Fear of Missing Out (FOMO). Many of these buyers now face the prospect of negative equity, especially if they live in Sydney.

Therefore, the RBA’s latest rate rise presents a double blow for many mortgage holders, lifting their cost of living while shrinking their wealth.

The good news: we are approaching the end of the rate hiking cycle

In the lead up to Tuesday’s monetary policy decision, most economists and financial markets were tipping the RBA to increase the OCR by 0.5 per cent, citing that it would need to follow the lead of the US Federal Reserve, which has hiked aggressively.

Westpac and Morgan Stanley were tipping a peak OCR of 3.6 per cent, whereas the bond market was even more hawkish tipping a 4.1 per cent peak.

The case for the RBA following the Federal Reserve is misguided for three key reasons.

First, unlike other nations, most Australian borrowers are on variable mortgage rates. This makes monetary transmission faster, meaning changes in interest rates flow through quicker to borrowers in Australia than elsewhere and the RBA doesn’t need to hike rates as aggressively to slow demand.

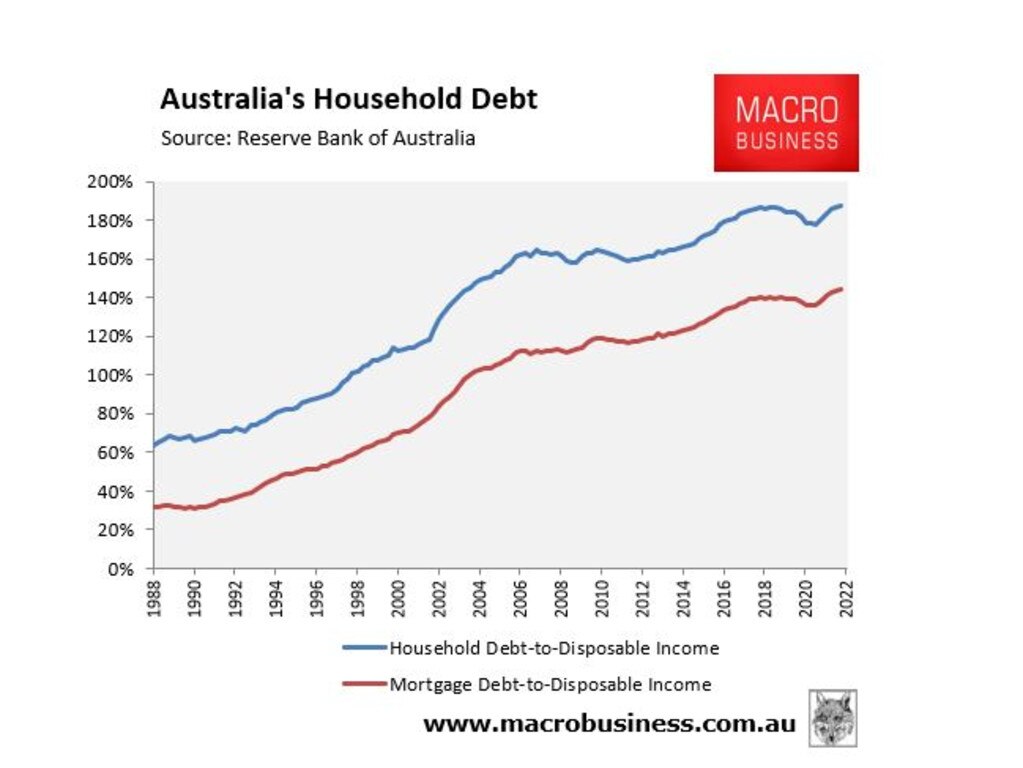

Second, and related to the above, Australia’s households are the second most indebted in the world behind Switzerland. Our household and mortgage debt also hit a record high relative to income in the June quarter of 2022. This high debt makes Australians more sensitive to interest rates than most other nations:

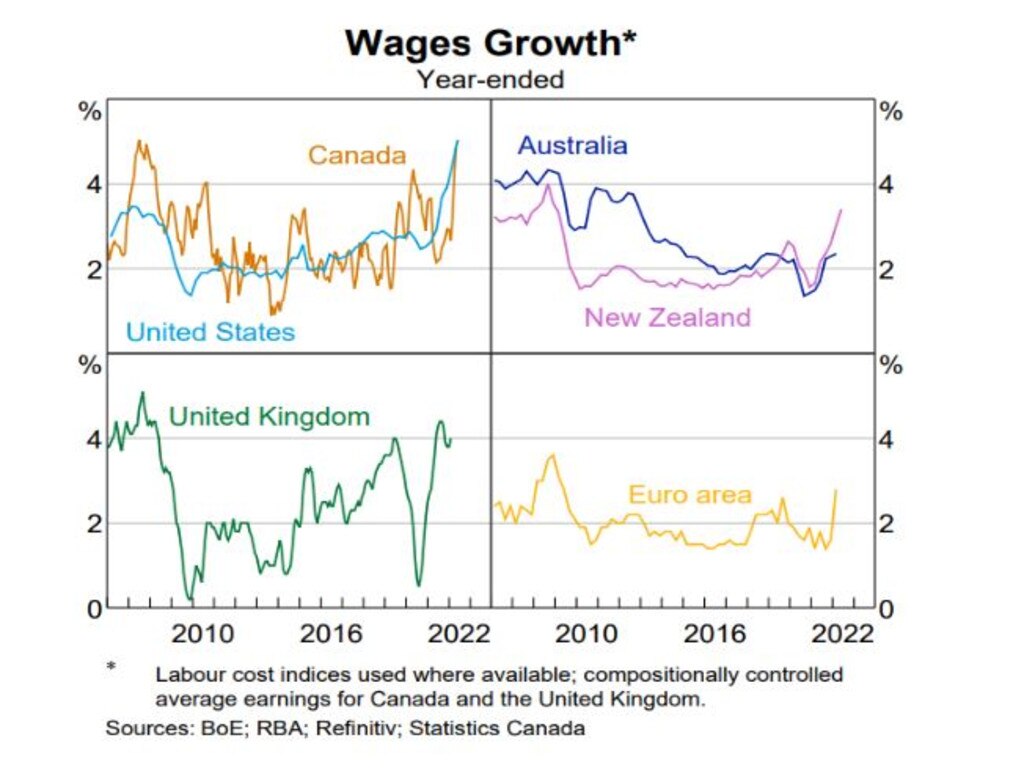

Third, Australia’s wage growth – the key measure of domestically driven inflation – is rising far more slowly than elsewhere:

Indeed, the 2.6 per cent wage growth recorded in Australia over the June quarter is well below the circa 3.5 per cent level the RBA previously stated was consistent with inflation within the target band over the medium term.

Recognising these realities, the RBA thankfully chose to return to normal operations and hike by only 0.25 per cent, instead of following the lead of the bond market or Federal Reserve.

In its monetary policy statement accompanying Tuesday’s rate decision, the RBA explicitly stated that Australian “wages growth … remains lower than in other advanced economies where inflation is higher”. It also acknowledged that “higher inflation and higher interest rates are putting pressure on household budgets, with the full effects of higher interest rates yet to be felt in mortgage payments”.

The RBA did, however, state that “the Board expects to increase interest rates further over the period ahead”, suggesting a few more 0.25 per cent hikes may arrive if data permits.

But the hawkish forecasts of Westpac, Morgan Stanley or the bond market seems unlikely. We look to be approaching the end of the current rate tightening cycle.

Has the RBA succeeded in bringing inflation down?

In Tuesday’s monetary policy statement, the RBA noted that while inflation would rise in the short-term, it expects “moderation in inflation next year”reflecting “the ongoing resolution of global supply-side problems, recent declines in some commodity prices and the impact of rising interest rates”.

Australia’s inflationary pressures are primarily imported, most visibly via petrol prices and materials. By contrast, the biggest domestic indicator of inflation – wage growth – remains soft and is disinflationary.

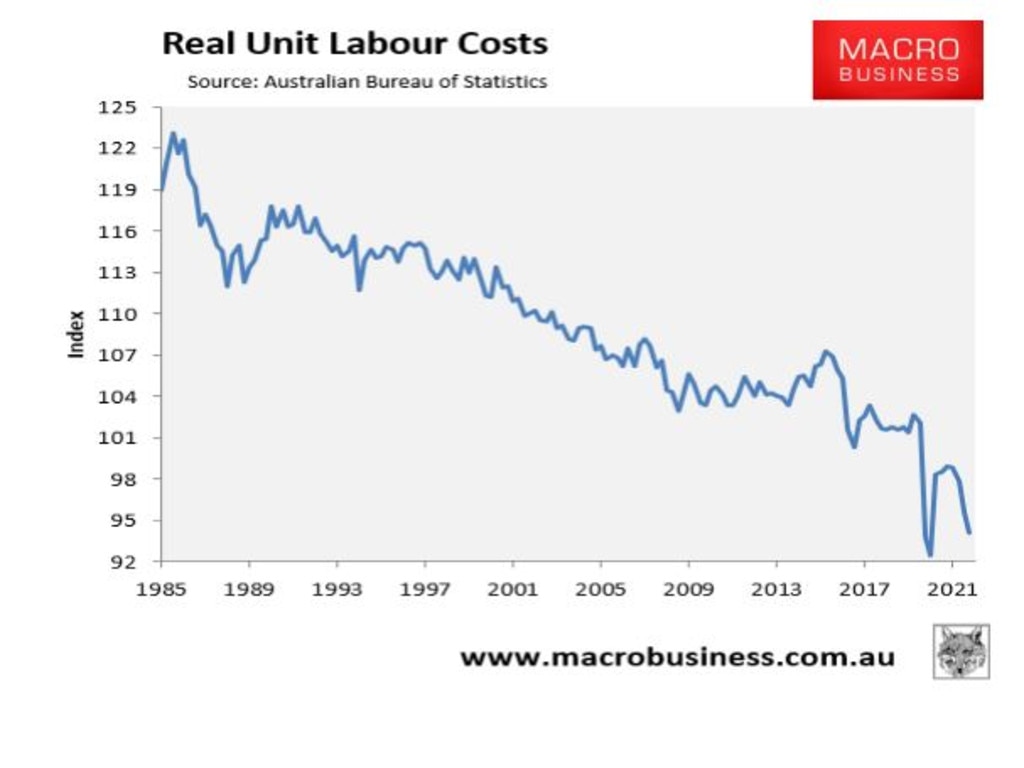

Consider Australia’s real unit labour cost (ULC), which according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics “are an indicator of the average cost of labour per unit of output produced in the economy” and “are a measure of the costs associated with the employment of labour, adjusted for labour productivity”.

Australia’s ULC collapsed 8.3 per cent below their pre-pandemic level in the June quarter, meaning wages are actually helping to lower Australia’s inflation rate:

Given most of Australia’s inflation is imported (cost-push), there was never strong justification for the RBA to hike rates so aggressively. Doing so merely exacerbates cost-of-living pressures for households and hammers the economy without relieving the very forces driving the inflation in the first place.

The two areas where domestically driven inflation pressures are emerging won’t be solved via higher interest rates either, and must instead be addressed through direct government intervention.

Property rents account for around 6 per cent of the CPI basket and are currently soaring at double digit rates. This means that rents will soon place significant upward pressure on inflation (other things equal).

Rents will also likely lift further next year given the Albanese Government has recently committed to increasing temporary and permanent migration to record levels, which will necessarily increase rental demand by the hundreds of thousands.

It’s a similar story with Australian energy prices. They account for 3.5 per cent of the CPI but have risen so dramatically that utility bills will double over the next year without government intervention to drop gas and coal prices.

Lifting the OCR will do nothing to stop these domestic inflationary pressures from biting. The solution rests with the federal government through: 1) moderating immigration to take the pressure off rents; and 2) reserving east coast gas for domestic use, alongside mining super profits taxes.

The RBA is ill equipped to fight inflation alone via the blunt tool of interest rates. It needs help from the federal government, most urgently via delinking east coast gas prices from the war-torn global market.

Leith van Onselen is Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.