Six pathways to Australia’s ‘economic armageddon’

THINGS are about to get very bad for Australia, an expert says. Here are six ways we’ll usher in “economic armageddon”.

THE future is going to be very bad.

It’s not a question of if or even when, but how. That’s the view of Australian economist John Adams, who says “economic armageddon” awaits us — we just don’t know what particular version it will take.

For the past two years, the former Coalition adviser has been sounding increasingly dire warnings about a looming global economic crisis in the face of record public and private debt, near-zero interest rates, excessive public spending and a massive housing bubble.

He first identified seven signs that the global economy was heading for a crash, later arguing the window for action had closed, before pointing out growing warning signs and highlighting a number of “myths” making us complacent to the danger.

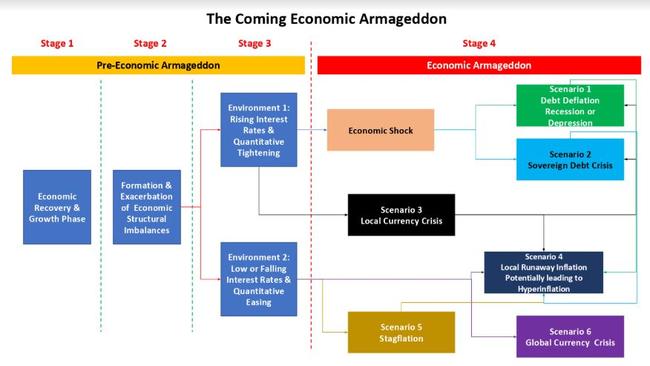

Now, Mr Adams has outlined six future scenarios he believes could occur — six “gates to hell” — based on two possible global environments. In the first, governments and central banks raise interest rates and withdraw monetary stimulus from financial markets. In the second, they keep interest rates low and keep printing money.

“Economic armageddon is a rapid adverse change in economic conditions that is likely to pose significant challenges for individuals to sustain their current standard of living, for businesses to maintain their commercial operations and for governments to maintain their current budgetary commitments,” Mr Adams said.

“Based on historical experience, the coming economic armageddon is likely to be an extreme economic event of a global nature, which may manifest itself in different forms. I have sought to define six scenarios of how an extreme economic event may manifest itself across the global economy and which will subsequently impact Australia.”

In the first environment of rising interest rates and quantitative tightening, the three scenarios are a debt deflationary recession or depression, a sovereign debt crisis, or a local currency crisis.

In the second environment of low or falling interest rates and quantitative easing, the three scenarios are runaway inflation potentially leading to hyperinflation, stagflation, or a global currency crisis.

All six scenarios are described in detail in Mr Adams’ piece below.

“The assessment that the world and Australia will experience one of these defined scenarios is based on the fact that both the global and Australian economies are experiencing record and abnormally high structural imbalances that in previous historical episodes have resulted in catastrophic economic and social outcomes,” he said.

Mr Adams said since he first began speaking out in February 2017, Australian politicians had not only failed to take action to reduce Australia’s chronic structural imbalances, but “these imbalances such as household debt, household savings and net foreign debt” had continued to worsen.

“The world is starting to see isolated examples of these various scenarios play out, whether it be runaway inflation or even hyperinflation in countries such as Argentina or Venezuela, an emerging currency crisis in Turkey and in Indonesia, political instability and riots in Jordan over inflation and taxes or a potential sovereign debt crisis in Italy,” he said.

“The Italian situation in the past few weeks has shown, in particular, how fragile the financial markets are and how quickly these markets can move. Within the space of two-and-a-half weeks, yields [payable interest rates] on two-year Italian bonds shot up over 2000 per cent from -0.135 per cent to 2.738 per cent.

“Future moves in the financial markets of this scale and speed have the potential to radically change economic conditions across the global economy within months, if not weeks.

“It remains most concerning that not only are many Australians and policymakers unprepared for an extreme economic event, Australians haven’t braced themselves as to how quickly such an event may materialise.”

The Six Scenarios Defining the Coming Economic Armageddon

by John Adams

Pre-economic armageddon: How we got here

Following the economic devastation of the GFC in 2008, economies around the world underwent a recovery and growth phase which was driven by internationally co-ordinated economic stimulus policies such as ultra-low interest rates, quantitative easing, tax cuts and increases in public spending aimed at stimulating economic activity and improving productivity, for example spending on infrastructure.

These policies encouraged greater economic activity resulting from private sector borrowing that funded both commercial investment as well as personal consumption. These policies were extraordinary in size and in some cases unprecedented and even experimental, such as with quantitative easing.

These policies have been responsible for either creating new structural imbalances or exacerbating existing imbalances to abnormally high and historic record levels in economies across the world.

In Australia’s situation, these structural imbalances have manifested themselves through record high asset prices (especially real estate), household debt (especially relative to disposable income), net foreign debt in excess of $1 trillion, record low interest rates and the lowest rates of household savings since December 2007.

In 2017 and 2018, economic growth driven by record levels of debt, rising business and consumer confidence, higher discretionary consumption and financial speculation in assets have created inflationary pressures (according to official measurements) in both advanced and developing economies.

Faced with historically chronic structural economic imbalances and building inflationary pressure, policy makers, specifically central banks, have the option to create two different economic environments in the coming period:

Environment 1: Rising interest rates and quantitative tightening

By raising interest rates and withdrawing monetary stimulus from financial markets via reducing central bank holdings of bonds and shares (known as quantitative tightening), governments and central banks can reduce the total quantity of money and credit, which can prevent further debt and inflationary pressure from building.

Within this environment, rising interest rates become a constraint on further economic growth. Individuals, corporations and governments find it difficult to meet existing debt obligations as debt servicing costs rise.

Environment 2: Low or falling interest rates and quantitative easing

Governments and central banks can keep interest rates low (or even reduce them further) and maintain other stimulatory monetary policies such as quantitative easing in order to maintain economic growth by fuelling further consumption and investment by suppressing interest rates as well as not burdening borrowers with higher debt servicing costs.

Scenario 1: Debt deflationary recession or depression

Governments and central banks tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates and withdrawing monetary stimulus to a level that produces a critical event of a major corporation or financial institution declaring financial difficulties or even insolvency which subsequently results in a partial or full default on existing debt obligations.

Historical examples of such critical events would be collapse of the Jay Cooke and Company in September 1873 (New York), Credit-Anstalt in May 1931 (Vienna) and Lehmann Brothers in September 2008 (New York).

A declaration of financial difficulty by a major corporation or financial institution results in either a collapse of confidence or an extreme shortage of liquidity, leading to a rapid selling of assets and escalating defaults on existing debt obligations.

When debt is defaulted upon, the debt (or credit) is eliminated from the total quantity of money, which subsequently results in the shrinking of the total quantity supply of money within an economy. If this process is allowed to continue unimpeded, then rapid falls in economic activity, income, prices, asset values as well as a rise in bankruptcies ensue.

Given that the modern financial system is both global and highly interconnected, a critical event involving a systemically large institution anywhere in the world is likely to spread across world financial markets and impact all economies, including Australia.

Based on historical experience, the severity and duration of the ensuing recession or even depression across the world will depend on size of the structural imbalances and the subsequent policy response.

In the US during the 1920-21 depression, debts were eliminated and the market was allowed to naturally restructure resulting in a depression lasting about 18 months with the following outcomes:

• US real GDP fell by 24 per cent

• Unemployment rose to 15.3 per cent

• Wholesale prices fell by 41.3 per cent

• Consumer prices fell by 10.8 per cent

• Share prices fell by 46.6 per cent (from 1919 to 1921)

• Commercial failures tripled from 6451 to 19,652 (from 1919 to 1921)

Alternatively, the Great Depression of 1929 lasted about 10 years in the US and caused greater economic hardship resulting from ill-advised government policy responses.

Importantly, for Australia, if a debt deflationary recession or depression were to commence and policy makers responded with significant levels of money creation and government spending stimulus measures that prevented the economy from restructuring this may lead to scenario 4.

Scenario 2: Sovereign debt crisis

A sovereign debt crisis occurs when the debts of an individual government (whether national, provincial or local) become too large that they are unserviceable resulting in the government either:

• Failing to pay principal and interest obligations as they fall due

• Renegotiating its existing debt obligations with bond holders (ie. a partial default or otherwise known as a haircut)

• Seeking a bailout from an external funding source, or

• Declaring bankruptcy and hence defaulting on all existing debt obligations (ie. a full default).

A sovereign debt crisis typically occurs in environments of higher interest rates, sluggish economic growth (low revenue growth resulting in inability to meeting spending and debt servicing commitments), political instability or when investors lose confidence that the government has the capacity to meet their debt obligations.

A sovereign debt crisis has the potential to engulf other sections of the global financial system and the global economy if either a partial or full default results in causing financial difficulties for bond holders (which is likely to be other governments or institutional investors such as banks and investment funds). The spreading of such a crisis is known as contagion.

The most recent example of a significant sovereign debt crisis was Greece in 2012. Through a bailout package from the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund, policymakers were able to limit potential contagion spill-overs to other European governments and financial institutions.

While Australia is unlikely at this stage to be at risk of a sovereign debt crisis, several governments across the world especially in Europe (such as Italy), Japan or specific states within the US (such as Illinois), are at significant risk of experiencing a sovereign debt crisis, which poses global contagion risks.

If a sovereign debt crisis does occur and further money creation and government spending stimulus measures are taken to prevent a restructuring of sovereign debt, this may lead to scenario 4 in the host country and may have inflationary spill-over effects for the global economy including Australia.

Scenario 3: Local currency crisis

A localised currency crisis occurs when an indebted country with significant amounts of received foreign direct investment and international debts lose the confidence of international investors to either generate expected returns or to meet their international debt obligations with currency that investors have confidence in.

Such a crisis typically occurs in an environment of rising foreign interest rates, where generating expected rates of returns for foreign investors or meeting servicing obligations of foreign debt are more difficult, especially where the local economy is experiencing high rates of inflation or has increased taxes on foreign capital.

The loss of foreign confidence results in investors withdrawing their capital from the country (otherwise known as capital flight) at a rapid rate which results in significant selling of the country’s currency on foreign exchange markets leading to a significant loss of the currency’s international purchasing power, otherwise known as currency depreciation.

Significant currency depreciation subsequently results in the value of a country’s international debts to skyrocket as more foreign currency is required to pay those obligations and makes imports more expensive to purchase, thereby causing prices to rise.

Without direct policy intervention, significant currency depreciation can lead to a country defaulting on its foreign debts leading to scenario 1. Alternatively, a country can deploy foreign currency reserves and raise interest rates sharply to maintain the value of the currency and international confidence. This may, depending on the scale and distribution of domestic private and public debts, lead to either scenarios 1 or 2.

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis began when, as a result of rising US interest rates, Thailand’s currency began to depreciate as investors withdrew foreign capital causing Thai firms to struggle meeting their international debt obligations and therefore resulting in debt defaults. The impacts of these defaults quickly spread to neighbouring Asian countries causing a financial meltdown across Asia.

Currently several developing countries such as Turkey and Indonesia are susceptible to currency crises which have the potential to impact the global economy, especially Australia given our $1 trillion net foreign debt and our low foreign exchange reserves.

Scenario 4: Local runaway inflation and potentially leading to hyperinflation

Governments allow inflationary pressure to build within an economy through the excessive creation of money and credit and as a result all prices across the economy generally rise, although prices of particular good and services which attract greater demand tend to rise more rapidly.

In order to prevent any slowdown in economic activity and deflation or to allow a government to continue running high levels of spending and fiscal deficits, governments continue to create money and credit at ever increasing amounts. This in turn leads to ever increasing growth in the total quantity of money (i.e. inflation) and increasing prices.

Runaway inflation occurs when governments lose control of prices increasing and requires a dramatic increase in interest rates to regain control. An example would include the current Argentine government, who in May 2018 raised interest rates to 40 per cent in order to regain control of rising prices which officially rose by 25 per cent over the preceding 12 months.

Governments that continue to print money in the face of runaway inflation will ultimately produce an exponential acceleration of prices and suffer hyperinflation. Famous episodes of hyperinflation include Germany in 1923 (322 per cent per month), Zimbabwe in 2008 (231 million per cent per annum) or Venezuela today (25,000 per cent per annum).

Hyperinflation generally results in the discontinuation of a country’s currency either by the government issuing a new currency (e.g. Germany) or for existing foreign currencies to be used instead as a substitution currency (e.g. Zimbabwe).

The global quantity of money and credit relative to size of the global economy is at a record historic high, which is now resulting in accelerating official rates of rising consumer prices across both developed (e.g. the US, Canada, Germany and Spain) and developing (e.g. the Philippines) economies.

If the growth of global money and credit and subsequent price increases goes unchecked, economies across the world, including Australia, will likely experience a breakout of high rates of general price increases.

Scenario 5: Stagflation

Stagflation occurs when an economy experiences low rates of economic growth while simultaneously experiencing accelerating rates of inflation. Western economies experienced stagflation during the late 1960s and through the 1970s. By 1979, inflation in the US reached 13 per cent per annum and over 20 per cent per annum in Britain in 1980, while economic growth remained subdued.

Historically, stagflation and its subsequent impacts typically manifests itself over a multi-year period.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, US Federal Reserve governor Paul Volcker raised prime interest rates to 21.5 per cent in order to end stagflation in America. During the ensuing recession in 1981-82, unemployment rose to over 10 per cent and forced closings, liquidations, and bankruptcies soared to the highest levels since the 1930s.

Analysts, including former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan, have recently publicly stated that economies across the world may experience stagflation resulting from the excessive creation of global money and credit as well as a mix of factors impeding economic growth including poor population demographics, weak productivity growth, reduced global trade due to rising trade protectionism, rising oil prices as well as slowing consumer demand and business investment resulting from high debt levels and rising debt servicing costs.

Any reduction in global economic growth is likely to act as a constraint on Australian economic growth which, given building inflationary pressure, may result in Australia also experiencing stagflation.

Were this is allowed to go unchecked, economies across the world might experience scenario 4 or may even produce a global currency crisis as described in scenario 6. If interest rates are raised to re-establish control of rising prices, then scenario 1 is likely to eventuate.

Scenario 6: Global currency crisis

A global currency crisis occurs when international confidence in a major currency such as the US dollar collapses, which results in breakdown in the international monetary system that prevents the settlement of cross-border financial and trade transactions between governments, corporations or individuals.

Since 1944, the US dollar has acted as the world reserve currency under the Bretton Woods Agreement. Under this agreement, international financial and trade transactions would be settled in US dollars which in turn could be exchanged for gold.

However, US president Richard Nixon in 1971 suspended the convertibility of US dollars for gold, resulting in a significant expansion in the total quantity of US dollars issued throughout the global economy. This has resulted in the official purchasing power of the US dollar in 2018 declining by 96 per cent relative to its 1913 value.

Concerned about the long-term value of the US dollar, governments of countries such as China, Russia and India have, in the past 10 years, attempted to mitigate the risk of a global currency crisis.

They have done this by amassing significant quantities of alternative forms of globally recognised money such as gold and silver and have instituted new monetary exchanges and international contractual arrangements to settle international transactions such as the petro-yuan oil futures contract (which was launched in March 2018) which allows China to buy oil in yuan (rather than US dollars) which can be subsequently be exchanged for gold.

China has also sought to mitigate the impacts of a potential global currency crisis by successfully lobbying for its currency to become an official international reserve currency. China achieved this by having the yuan included in the IMF’s special drawing rights basket of currencies which was approved by the IMF in 2016.

Continued accelerated creation of additional US dollars through ultra-low interest rates and new rounds of quantitative easing would further diminish international confidence in the US dollar as a global reserve currency and may trigger a global currency crisis.

Previous collapses of the international monetary system such as in 1914 resulted in significant geopolitical and economic instability until a new monetary standard was established.

In a new global currency crisis, international institutions such as the IMF and major economies would be required to establish a new global monetary standard that would facilitate international commerce.

A new global monetary standard is likely to reset the value and purchasing power of all currencies, including the Australian dollar, relative to the new global monetary standard.

This reset would subsequently alter the value of Australia’s assets and debts which may dramatically impact the wealth of individual Australians, corporations and governments.