Ten myths making Australians complacent about looming ‘economic armageddon’

BELIEVE it or not, many Australians believe these 10 money myths — and it could be putting us all in danger.

WE USE only 10 per cent of our brains. Undercover police have to identify themselves if you ask. Einstein failed at maths.

There are many common myths which, no matter how many times they are debunked, continue to live on in the public consciousness.

And according to a former Coalition adviser, many of us similarly believes in a number of myths about the economy, leaving the country in the dark and unprepared to deal with a looming global crisis.

Economist John Adams has issued a series of increasingly dire warnings in the past two years— he first identified seven signs that the global economy was heading for a crash, later arguing the window for preemptive action had closed, before pointing out a further 10 warning signs based on developments in world markets.

“My warnings have been based on a series of economic metrics which have reached historically abnormal levels and which have in similar circumstances led to catastrophic economic consequences,” Mr Adams said.

Since issuing his first warning, he has spoken to many Australians about their views on the economy and their general understanding of economics and public policy. “Through these conversations, I have identified a series of common misconceptions or myths which it appears many Australians anecdotally believe,” he said.

Those misconceptions may lead to a “misunderstanding as to the true nature of the state of the Australian economy and the real risks to which Australians are exposed to regarding their personal economic security in the case of an international economic shock”.

“These misunderstandings are leading to a significant level complacency among large sections of the Australian people who are completely unprepared for the coming economic crisis which will impact their lives in literal and fundamental ways,” he said.

Earlier this year, Liberal MP Tim Wilson echoed Mr Adams’ concerns in a speech to Parliament, breaking ranks with the government to criticise economic policy settings as inadequate to deal with a possible global downturn.

Mr Wilson called out “alarming” rates of public and private debt spurred by record low interest rates, inflated asset prices and excessive public spending. “The warning signs are all there,” he said.

Mr Adams has now outlined the 10 economic myths he believes are making Australians complacent about the “coming economic armageddon”.

“Hopefully, by bringing attention to these commonly held myths, individual Australians will re-examine the assumptions that are guiding their economic decisions, do their own homework and upon learning the facts regarding the economy and the global financial system, will revise their expectations and make appropriate financial decisions,” he said.

JOHN ADAMS’ 10 ECONOMIC MYTHS

MYTH 1: THERE WILL BE NO FINANCIAL CRISIS IN OUR LIFETIME

In June 2017, the then US Federal Reserve governor Janet Yellen said in relation to the possibility of a future financial crisis: “I do think we’re much safer and I hope that it will not be in our lifetimes and I don’t believe it will be.”

This statement is almost identical to the declaration made by world famous economist John Maynard Keynes in 1927 who stated, “we will not have any more crashes in our time”, only to have the Great Depression occur two years later in 1929.

Unfortunately, today’s financial bubble, as measured by various metrics, including asset valuations and debt relative to income, is either equivalent or worse than what happened in the lead-up to the Great Depression.

MYTH 2: TODAY IS THE ‘NEW NORMAL’

In December 2012, the now Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) governor Dr Philip Lowe made the astonishing admission in a speech that the RBA found it hard to determine, given the economic conditions at the time, what should be considered “normal” economic behaviour.

That is, household spending, household savings, employment, wages growth and therefore interest rates. Five years later, in November 2017, Dr Lowe stated, “We are still searching for what is normal.”

Unfortunately, the Australian economy today is experiencing structural imbalances in household debt and net foreign debt, which are at historically high and abnormal levels. Therefore, the economy cannot resemble anything close to being normal relative to historical experience.

MYTH 3: INFLATION IS LOW

According to the RBA, inflation is defined as an increase in the general level of prices throughout the economy as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is a statistical index that measures the changes in prices of a fixed basket of goods and services.

More than a century ago, economists’ definition of inflation was not an increase in prices, but an increase in the money supply, that is, “to inflate” the quantity of money within an economy. The consequences of increasing the supply of money within an economy would subsequently lead to a general increase in prices.

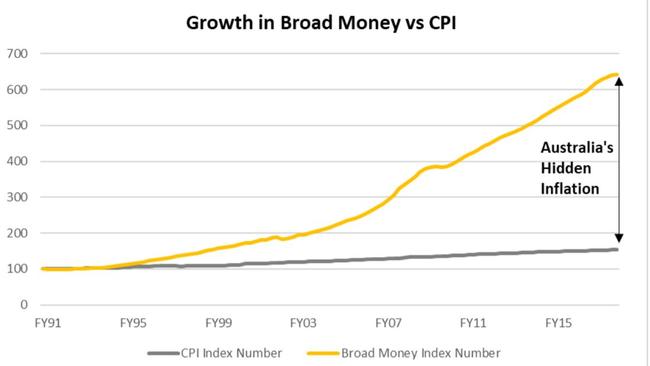

According to RBA figures, the money supply as measured by “broad money” grew from 1992 to 2017 at an average annual rate of 7.5 per cent, as opposed to the CPI, which grew over the same period at 2.44 per cent.

The difference between the growth of broad money and the CPI can partly be explained by the prices of goods and services not included in the CPI basket, including real estate and financial assets such as shares and bonds.

It is also due to methodological changes implemented by the Australian Bureau of Statistics that have led to the underestimation of the official CPI, including the use of geometric means and hedonics, otherwise known as the “quality adjustment” method.

This “hidden inflation”, which has been caused by the excessive creation of money and credit by the RBA, is to a large degree the cause for the current household debt bubble in Australia as well as the cost-of-living pressures being experienced by a large number of Australians.

MYTH 4: ANY RISE IN INTEREST RATES WILL BE GRADUAL

Interest rates and lending products in Australia are determined by a mix of factors including the RBA (short-term rates), prudential regulation set by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, the pricing decisions of banks, domestic economic conditions as well as the international credit market.

Unfortunately, Australia’s net foreign debt is in excess of $1 trillion — more than 56 per cent of gross domestic product — which means that Australian financial and corporate institutions are heavily exposed to international overseas economic events, especially as they pertain to the international credit market.

Given that most major bond markets are in a historical multi-century bubble — as recently stated by former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan — a spike in official inflation estimates and a general loss of economic confidence in the ability of governments and corporations to meet their debt obligations could lead to a significant fall in international bond prices and therefore a corresponding rise in bond yields (or payable unofficial interest rates).

Any increase in the cost of debt on the international credit market would flow through to domestic banks and be passed on to Australian borrowers, independent of the RBA’s official interest rates.

MYTH 5: AUSTRALIAN HOUSE PRICES WILL NEVER FALL

Australian real estate prices are a function of the ability and willingness of Australians to pay for real estate (demand) as well as the cost and quantity of supplying real estate (supply).

In the past nearly three decades, the demand for real estate has been driven by various factors including the ability of Australians to borrow large amounts of money to purchase real estate, either through record low interest rates or new mortgage products such as interest-only loans. This has sent real estate prices substantially higher.

The concentration of credit in Australian housing as a proportion of the economy has grown phenomenally since June 1991 from 21.07 per cent to 95.33 per cent as of June 2017.

When higher global interest rates lead to a popping of the global debt bubble, debt servicing will become more difficult, either from higher interest rates or a loss of income resulting from unemployment. Increased mortgage stress and defaults will lead to the forced selling of real estate sending prices lower.

This process led to dramatic falls in real estate prices during the global financial crisis (GFC).

According to statistics from the Bank of International Settlements, prices for all forms of real estate fell 55.19 per cent in Ireland (April 2007 to March 2013), 18.76 per cent in the UK (October 2007 to March 2009), 13.92 per cent in Iceland (March 2008 to January 2010) as well as 31.46 per cent in the US for existing dwellings only (March 2006 to September 2011).

MYTH 6: A TRIPLE-A CREDIT RATING MEANS IT IS SAFE

According to the professional credit rating agencies, financial instruments that are rated AAA are supposed to be of the highest possible investment grade — that is, they have extremely low insolvency risk from changes in business, financial and economic conditions.

However, as documented in the best-selling book The Big Short, a staggering proportion of mortgage-based debts in the form of collateralised debt obligations, or CDOs, were rated AAA by leading credit rating agencies in the run-up to the 2008 GFC, when in fact they were of poor credit quality.

According to the credit rating agencies, credit rating statements issued by them are merely their “opinion” and not a “statements of current or historical fact”.

Faulty credit ratings in the run-up to the GFC led to several Australian class action law suits resulting in, for example, the Federal Court of Australia in 2012 upholding a ruling that Standard & Poor’s was negligent and had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in giving a financial product a AAA rating.

According to a 2017 Brookings Institute report, much of the reform relating to credit rating agencies in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act 2010 has still not been enacted by regulators, including making credit rating agencies legally liable for their ratings in a manner similar to an “accounting firm or a security analyst”.

MYTH 7: YOU OWN YOUR GOLD

Under Part IV of the Banking Act 1959, the Governor-General has the power to sign a Proclamation that compels individuals and entities to hand over all gold bullion (except for gold connected to an individual’s profession or trade) above a prescribed weight to the RBA within one month or face criminal prosecution.

The RBA, under section 44 of the Banking Act 1959, will publish the price at which individuals or entities are to be compensated for the gold bullion that is confiscated by the Federal Government.

MYTH 8: BANK BAIL-INS CAN’T HAPPEN IN AUSTRALIA

A bank bail-in is where a bank recapitalises its balance sheet by confiscating investor’s assets in exchange for shares in the bank. The most famous bank bail-in example was when the Bank of Cyprus in 2012 confiscated 40 per cent of deposits above 100,000 euros in exchange for shares in the bank.

According to a Senate Economics Committee inquiry held in February 2018 into the recently passed legislation, Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2017, hybrid securities include conversion and write-off provisions within their detailed contracts and can technically be bailed-in.

According to the RBA, as of November 2017 the size of the domestically issued hybrid securities market, including Australian and foreign financial institutions, was $94 billion.

In July 2017, the former chairman of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Greg Medcraft raised concerns over hybrid securities being sold to Australian retail investors and noted that countries such as the UK have banned the sale of such securities to retail investors.

MYTH 9: BANK DEPOSITS ARE GUARANTEED BY THE GOVERNMENT

According to the 2018-19 Federal Budget (Budget Paper 1, Statement 9), the government’s Financial Claims Scheme — that is, the bank deposit guarantee scheme — provides up to $20 billion of deposit insurance to each eligible authorised deposit-taking institution as well as an additional $100 million in administration costs for deposits up to $250,000.

As of December 31, 2017, the scheme provided insurance for up to $890 billion in deposits.

However, the federal government has not made any financial provision to pay money under the scheme if it ever was required to do so, even though it was advised to do so by the International Monetary Fund in 2012.

During an economic recession or even a financial crisis, federal government revenue would be expected to decline substantially, causing the budget to experience a significant fiscal deficit.

Given that gross government debt is expected to peak at $578 billion by 2020-21, it remains a questionable assumption whether, under severe economic conditions, the federal government would be able to finance its existing debt, finance new debt resulting from a larger budget deficit as well as provide billions of dollars under the Financial Claims Scheme, especially if multiple financial institutions require deposit insurance.

Under such conditions, the federal government would not be legally obliged to make insurance payments to depositors if eligible institutions became insolvent, but rather it would retain the legal discretion as to whether or not it wished to activate the scheme.

According to the 2018-19 budget papers, the preferred method of meeting the financial obligations under the Financial Claims Scheme is via a new bank levy. If a new bank levy is imposed, then the deposits under the scheme are ultimately guaranteed by the customers and shareholders of other banks as opposed to the federal government.

MYTH 10: BANKS AROUND THE WORLD ARE WELL CAPITALISED

Under the Basel III capital framework which was issued by the Bank of International Settlements in 2010 and adopted across the world, sovereign debt has been assigned a zero-risk weighting, which effectively means that the global financial system is assuming that no government around the world will default on their debt obligations.

This means that it is likely that capital requirements that have been set for banks and other financial institutions across the world will be insufficient to deal with financial losses resulting from an economic crisis if, for example, another Greek-style sovereign debt crisis were to eventuate.