‘Australian nightmare’: Crisis we can’t ignore

A leading economist says there’s an “obvious” link between Australia’s migration explosion and the housing crisis - and a straightforward solution to end the pain.

Whether you’re for it or against it, it’s undeniable that by virtually any metric, Australia is in the midst of an unprecedented experiment with mass immigration.

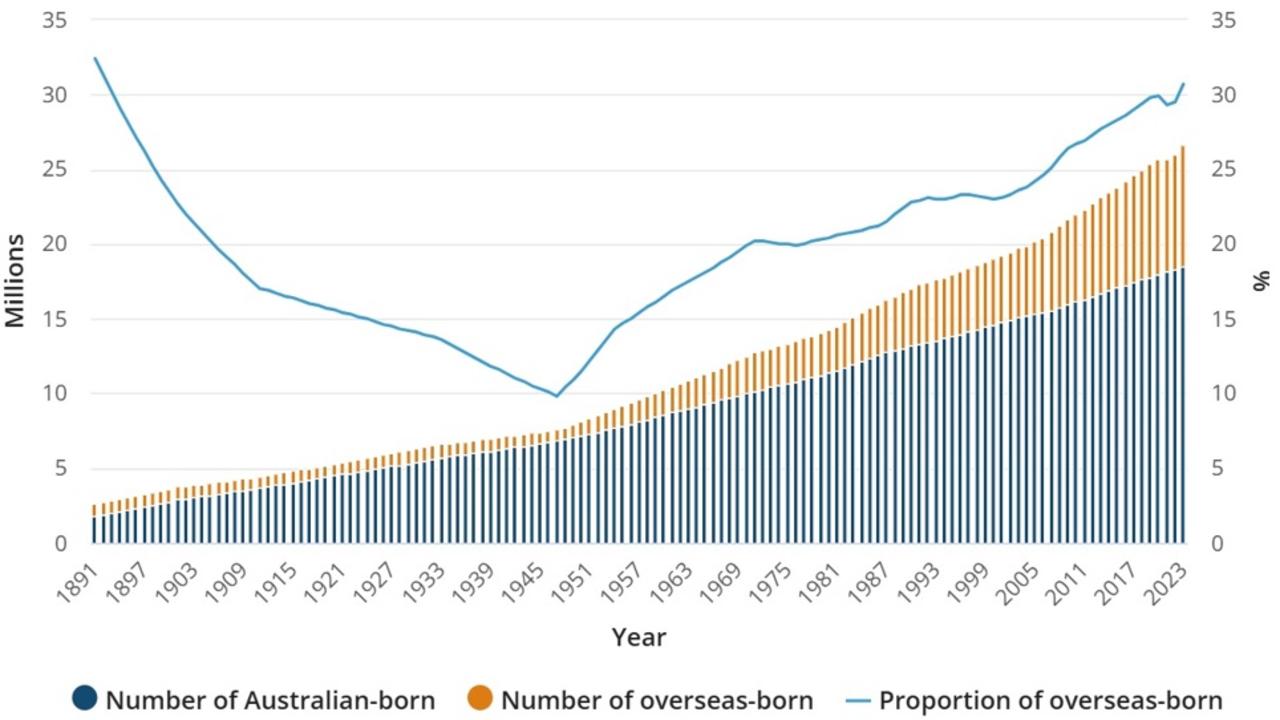

The figures are striking.

Between 2000 and 2023, Australia’s population grew by 40 per cent — the fastest rate of any developed nation.

More than 30 per cent of Australia’s population in 2023 was born overseas, for the first time since 1893.

For every one baby born in Australia now, four migrants arrive. And many of those babies are themselves born to migrants.

The overseas-born population bottomed out at 9.8 per cent in 1947 and has been climbing steadily ever since, in almost a V-shaped recolonisation.

In the 60 years after World War II, net overseas migration — arrivals minus departures — averaged 90,000 per year.

Despite large influxes of migrants from Europe after the war, that figure only reached 150,000 twice in those six decades.

When John Howard kicked off the “Big Australia” boom in the early noughties, net overseas migration more than doubled from its historical average.

But that was just a taste of what was to come.

After Covid, net overseas migration skyrocketed to an eye-watering record of 536,000 people in 2022-23, dipping slightly to 446,000 in 2023-24.

“We’re not against migration,” said Frank Carbone, Mayor of multicultural Fairfield in Sydney’s west.

“Migration is the foundation this country has been built on — but it’s always been a sensible, regulated policy. At the moment it feels like the policy under Albanese has been unregulated and uncontrolled. It’s one of the biggest mistakes I’ve ever seen in public life.”

The surge has been driven by international students, who make up the vast bulk of temporary migration numbers. A record 197,000 arrived in February alone and there are now more than 850,000 in the country.

The permanent migration program, currently set at 185,000 places, is a smaller contributor to net overseas migration, since 60 per cent of granted visas are already living in the country — of those, around 25,000 a year are former “temporary” students.

Today, a new migrant arrives to live in Australia every 44 seconds — that’s nearly 2000 people per day, or more than four full Boeing 747s.

All the while, Australia’s birthrate continues to fall, now at a record low of 1.5 per woman. The birthrate fell below replacement level of 2.1 in 1976 and never recovered.

With zero net overseas migration, Australia’s population would be declining.

But at the current rate, the country is adding nearly a Canberra every year.

The federal budget forecasts another 1.8 million people over the next five years — roughly an Adelaide and a Hobart.

In the next 40 years, Australia’s population is officially tipped to grow by 13.5 million — another Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane — to reach 41.2 million by 2065.

And that number, from the Centre for Population’s 2024 Population Statement, assumes net overseas migration of only 235,000 per year.

Both major parties have vowed to reduce migration in the face of growing public backlash — Labor by a bit, the Coalition by a bit more — and build more homes.

‘Australian nightmare’

As hundreds of thousands of migrants arrive every few months, more than half of them settling in Sydney and Melbourne, many young families are leaving.

In Sydney, which now has the second least affordable housing in the world second only to Hong Kong, the exodus in recent years has been stark.

NSW saw net overseas migration of 120,073 (202,781 arrivals and 82,708 departures) in the 12 months to September 30, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

In the same period, a net 29,505 people left NSW for other states (81,410 arrivals and 110,915 departures).

Fairfield has been dubbed Australia’s “refugee capital”, settling roughly half of the country’s humanitarian migrants from countries including Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan.

“All I can say is Fairfield’s full,” said Mayor Carbone, an independent.

“There isn’t an empty house, there’s nothing available for anybody. Fairfield is on the outskirts — I can only imagine what it’s like everywhere else.”

Mr Carbone said every country “needs a migration policy but it needs to be a sensible, sustainable policy”.

“What we’ve had over the past few years with more than one million people coming in has had a huge impact on the quality of life for every Australian,” he said.

“It’s put pressure on housing, pressure on rents and general cost of living. Quite clearly the government has made a huge mistake, because what I see in the street is people competing for the most important things in life that we need and should all be able to have — housing, food, energy.”

Mr Carbone said those necessities had grown unaffordable for working people, pensioners and “even for those migrants who’ve come in and the government’s just dumped at our doorstep”.

“It’s quite clear with the huge increase that the government has brought in that this has put our economy out of step,” he said.

“I’m not talking about the bottom line or the GDP. It might suit Treasury to have higher numbers but it doesn’t suit our community. Everyone realises we can’t build enough houses to accommodate one million coming in overnight.”

Growing up in Fairfield, Mr Carbone said it was a place immigrants would settle “but it was a place of opportunity as was the whole country, where you knew if you worked hard you could build a better future and you could have home ownership”.

“They’ve turned the Australian dream of owning a home and raising a family into an Australian nightmare quite simply because they were more worried about the bottom line,” he said.

Housing’s big squeeze

Labor has promised to build 1.2 million new homes by 2029, or 240,000 a year.

The Coalition claims it will build 500,000 homes “more quickly” under its plan.

Labor is aiming to bring net overseas migration to 230,000 over the long-term, and is forecasting 335,000 this financial year.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton vows the Coalition would slash numbers to 160,000 “straight away”.

“At the moment the forecast net overseas migration for the next five years comes to an outcome below the number of additional houses that the government has said in its plan it will build,” said Dr Abul Rizvi, former deputy secretary of the Immigration Department.

“If those two forecasts are realised we will actually have a surplus of houses. That’s the crucial question.”

Dr Shane Oliver, chief economist and head of investment strategy at AMP, insists tying immigration to housing capacity is “just a statement of the obvious”.

He argues solving the housing crisis will require both cutting back demand by lowering immigration, at the same time as boosting supply.

“The problem is that with immigration at one stage being above 500,000 and population growth of about 650,000, in that situation you need to build about 250,000 homes a year,” he said.

Australia currently builds about 180,000 homes a year — including houses and units — “if we’re lucky”, with the past few years seeing around 160,000 to 170,000 completions.

“The highest we ever got to was about 225,000 in the unit building boom between 2015 and 2019,” Dr Oliver said.

The rate of new home building since Covid has been nowhere near fast enough.

In 2023-24, building approvals fell by 8.8 per cent to just 158,690 new starts, the lowest level in more than a decade.

Assuming an average of 2.5 people per household, Australia had a shortfall of 62,000 homes to accommodate population growth last financial year — although this was an improvement on 2022-23, when the shortfall was 110,000.

The undersupply was greatest in Western Australia where just 48 per cent of new homes needed were built, followed by the Northern Territory (56 per cent), Queensland (61 per cent), NSW (74 per cent) and Victoria (82 per cent). Only Tasmania and the ACT built enough homes to keep up.

“The government is forecasting population growth to fall over the coming years to a level at which it should be possible to construct enough new housing,” PropTrack senior economist Anne Flaherty said.

“The difficulty, however, will be making up for the deficit in new homes built in recent years. The government is focused on increasing supply, however it’s not an immediate fix. Building homes where people want to live is critical but will take time.”

Starting from when annual net overseas migration spiked in the second half of the 2000s — without a corresponding increase in home building — Australia has built up a chronic shortage of housing that gets bigger every year.

“That led to this ongoing trend of chronically high home prices in relation to people’s income,” Dr Oliver said.

AMP estimates the current shortfall is between 200,000 to 300,000 dwellings.

“Basically if you get [net overseas migration] back to about 200,000, and allowing for population growth and demolitions, you’re probably needing to build about 180,000 dwellings in that situation anyway,” he said.

If immigration is cut back to 200,000 and 240,000 homes per year are built, “over five years I reckon we probably would have gotten on top of the housing shortage”.

“After that point then we should calibrate the level of immigration to the capacity of the home building industry to supply homes,” he said.

“Longer term we need to try and decentralise to take pressure off our capital cities. We did start to see a mini version of that through the pandemic when working from home allowed more people to move to regional centres. That sort of stopped in its tracks when people were told to come back to the office.”

Experts have warned that the signature housing policies from the major parties — Labor has proposed 5 per cent deposits for all first home buyers, the Coalition would allow accessing superannuation — would simply increase demand.

“It just makes the situation worse and pushes the price up,” said Dr Oliver.

“The only beneficiaries are old people like me. Maybe it benefits the 11 million voters who already have a house, but it’s not a long-term sustainable situation. Probably the single biggest cause of social dissatisfaction in Australia is this gap between the haves and have-nots with respect to housing. You have to get it fixed.”

A report from REA Group last month found rental affordability in Australia had plunged to its lowest level on record.

Since the start of the Covid pandemic in March 2020, rents nationally are up 48 per cent, far outstripping income growth of 19 per cent.

NSW renters face the worst affordability of any state — median advertised rents in Sydney have surged by $230 since Covid to $730 per week, or nearly $12,000 extra a year.

Several studies have sought to debunk any link between international students and the rental crisis.

Official data shows, however, that recent migrants, both permanent and temporary, are more likely to be renters. According to the ABS, 60 per cent of recent permanent arrivals rented in the five years to 2021, and Census data in 2021 showed 65 per cent of temporary migrants were renters.

‘More immigrants to build homes’

Dr Oliver said commentators “get tangled in knots saying we need more immigrants to build the homes” but the numbers simply didn’t add up.

Migrants, and particularly international students, are less likely to work in construction than most other industries.

So the problem is one of both supply and demand. Migration contributes to both — but at the moment, too much from column B, too little from column A.

“Most don’t go into home building,” Dr Oliver said.

“You [could] skew the visa requirements under the skilled category to give preference to people with home building skills … but most of the time we find the net impact is one that worsens the undersupply problem when immigrants arrive. I think immigration has been a very good thing for Australia, but you need to get the balance right.”

Master Builders Australia (MBA) forecasts the construction industry will need an additional 130,000 workers to meet Labor’s 1.2 million home target “by the skin of its teeth”.

The Housing Industry Association (HIA) puts the shortfall at 83,000 tradies.

Industry groups argue some of those workers will need to come through skilled migration.

Unlike New Zealand, Canada and the UK, Australia has no dedicated trade visa stream.

MBA has called for streamlining visa pathways, embracing mutual recognition of qualifications from overseas, lowering English-language requirements for some non-licensed trades, and offering fast-track to permanent residency.

Even if demand is reduced by lowering immigration, building more homes, as both parties have promised, won’t be easy.

Increasing state and local red tape, labour shortages — particularly apprentices — rising materials costs and record numbers of developers going under have made it harder than ever to build new homes.

Approval times have blown out, and the time it takes from approval to completion has roughly doubled compared with 10 years ago.

A block of units now takes an average of 2.8 years to build, while stand-alone houses take about one year and four months, compared with seven months in 2015.

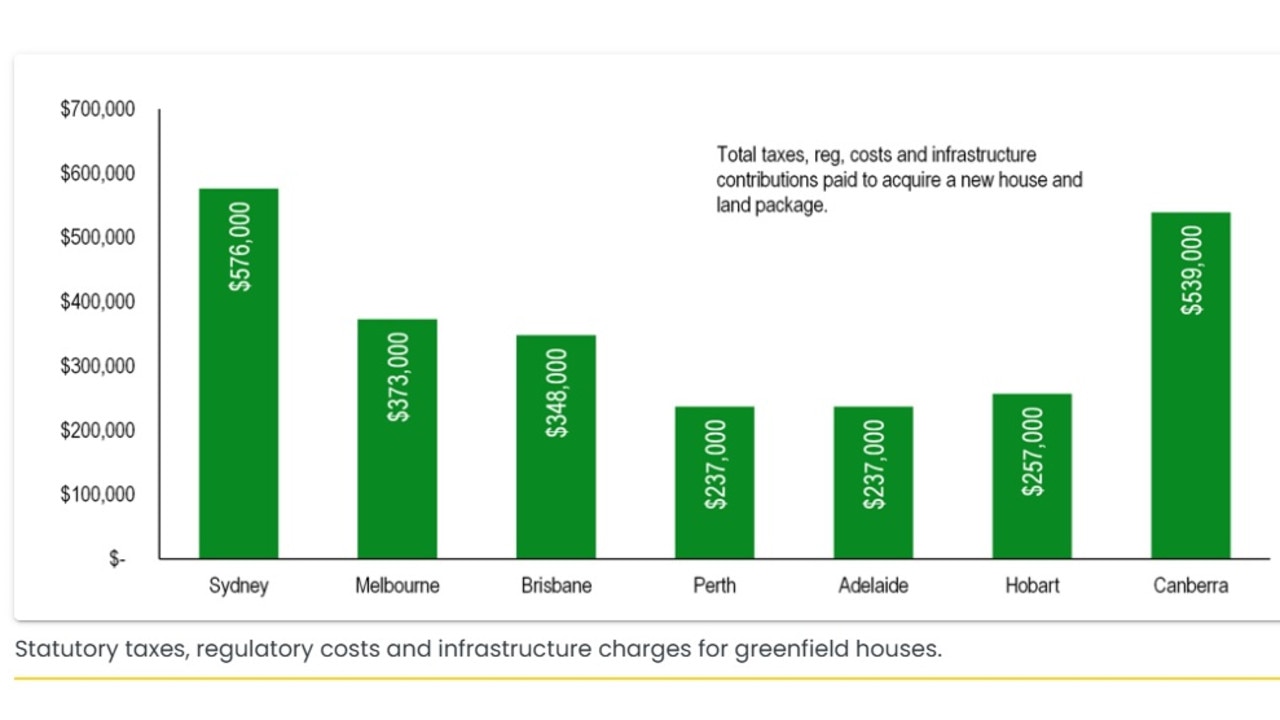

The HIA, in a report last month, found half the cost of a new house and land package in Sydney was government taxes, regulatory costs and charges — to the tune of $576,000.

For a new apartment that number was $346,000, or 38 per cent of the cost.

Housing taxation has doubled in just five years, according to the HIA analysis, at precisely the worst time.

“It is incongruous that governments set home building targets, while at the same time tax new home building even more,” HIA chief economist Tim Reardon said.

Dr Oliver said the HIA’s analysis was correct.

“[Tying immigration to housing capacity] does sound a bit like central planning but the problem is the housing industry has been so affected by government intervention — [it would be] just a more rational form of government intervention,” he said.

“Immigration is something that’s always controlled by the government, and so is the ease with which people can build homes. It’s just a statement of the obvious.”