Australian housing affordability one of the worst in the world

A new grim report makes for difficult reading. It proves that Australians are facing a situation almost unparalleled globally.

Housing affordability has been described as “disastrous” among places like Australia as it ranks as one of the worst places in the world to try and buy a home, with young people described as “victims” in a new report.

Unsurprisingly, Sydney topped the list for being the most unaffordable in Australia and was only behind Hong Kong across the world.

In fact Sydney has had the first, second or third least affordable housing of any major market in 15 of the last 16 years, the report showed.

Another report released in March found buying a house in Sydney is less affordable than in the notoriously expensive markets of London, Los Angeles and Miami.

However, almost all of Australia’s major capitals ranked in the top 25 per cent least affordable markets for middle-income home buyers, The Chapman University Frontier Centre for Public Policy’s Demographia International Housing Affordability report found.

The report from US academics examined the ability of “median income” households to purchase median-priced homes and investigated the housing markets in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Ireland, New Zealand, Singapore, United Kingdom and the United States.

Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth were all a part of the least affordable 25 per cent of cities in the list of 94 markets examined in the study.

It showed that Sydney has an impossibly unaffordable market as the cost of housing was 13.8 times the median income in the city.

Melbourne, was also categorised as impossibly unaffordable, with cost of a home 9.8 times more than the median income, while even “the far less renown” Adelaide had a similar affordability crisis, the report noted.

“For decades, home prices generally rose at about the same rate as income, and homeownership became more widespread,” the report said.

“But affordability is disappearing in high-income nations as housing costs now far outpace income growth. The crisis stems principally from land use policies that artificially restrict housing supply, driving up land prices and making homeownership unattainable for many.”

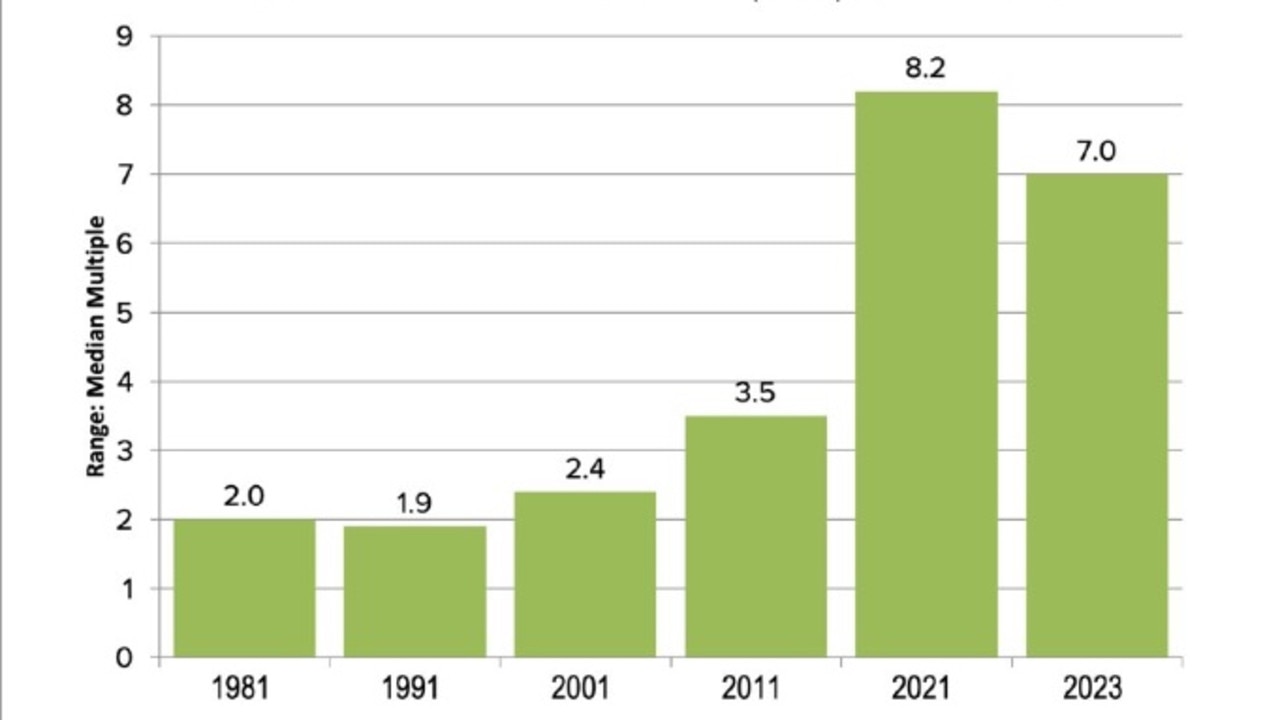

As late as about 1990, national price-to-income ratios were “affordable,” at 3 or less of the median income in Australia.

But the report revealed that the range between the most affordable and least affordable markets has grown from two times the median income in 1981 in Australia soaring to seven times by 2023.

It blamed urban planning policies seeking to limit the expansion of urban sprawl and increase the density of cities as a huge contributor to housing unaffordability.

“The middle-class is under siege principally due to the escalation of land costs,” the report said about overall global economic policies.

“As land has been rationed in an effort to curb urban sprawl, the excess of demand over supply has driven prices up.”

For the first time since releasing the report in the past 20 years, the US academics added a new category for housing affordability – “impossibly unaffordable”.

“The term ‘impossible’ was selected to convey the extreme difficulty faced by middle-income

households in affording housing at a median multiple of nine,” it said.

“This level of unaffordability did not exist just over three decades ago. Furthermore, securing financing for a house at this median multiple is largely impossible for middle-income households.”

The study praised Singapore’s government for turning a “desperate housing situation” in the 1960s to now more than 90 per cent of citizens buying their own homes.

“Singapore … was characterised by unhygienic slums and crowded squatter settlements,” the report said.

“To address this, Singapore established the Housing and Development Board (HDB), adopted policies to encourage a property-owning democracy in Singapore and to enable Singapore citizens in the lower middle-income group to own their own homes.”

As a result of the pandemic, the report estimated that in San Diego nearly two-thirds of the US house price increase in the demand shock could be attributed to the shift to remote work – a problem that has also been playing out in Australia.

The lack of homes being built to add to housing supply also has far reaching consequences.

Bendigo Bank’s chief economist, David Robertson said the recent federal budget doubled down on commitments to work with states to build 1.2 million homes by 2029.

“But house prices continue to reflect demand exceeding supply with another 0.8 per cent added to dwelling prices in May, with big increases in Perth and Adelaide seen over the last three months,” he said.

“How quickly supply can be added to deal with housing affordability will have consequences for inflation, but it’s an uneven experience at present with listings in Victoria and Tasmania sharply higher in contrast to other states and territories.”