‘Back to the 1950s’: Band-Aid migration can’t fix low fertility rates — but no one has the solution

As Australia faces record population growth, other countries are grappling with the opposite problem. And experts are divided on the solution.

As Australia’s government unveils a new migration strategy to clamp down on increasingly out-of-control population growth, other countries are grappling with the opposite problem.

While Australia brought in a record 500,000 migrants last financial year, Japan posted its own record — a total population decline of nearly 800,000.

The figures, released in June by Japan’s internal affairs ministry, showed deaths hit a record high of more than 1.56 million while births hit a record low 771,000.

Even a record 10 per cent increase in foreign residents to 2.99 million couldn’t halt the 14th straight year of declining population, which reached 122.42 million in 2022.

According to United Nations projections, many countries are expected to see population declines over the next three decades due to a combination of declining fertility rates and emigration.

Japan’s situation is uniquely dire due to the age of its population — 29 per cent of Japanese are now aged 65 or older, and one in 10 are aged 80 or older.

“Japan is standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society,” Prime Minsiter Fumio Kishida said in January. “Focusing attention on policies regarding children and child-rearing is an issue that cannot wait and cannot be postponed.”

Birthrate battle

Like many developed nations, Australia is grappling with the consequences of decades of gradually declining birthrates.

“Since 1976, Australia’s total fertility rate has been below replacement level (about 2.1 births per woman),” the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) says. “Replacement level is the level at which a population is replaced from one generation to the next without immigration.”

The fertility rate peaked at 3.55 in 1961, the same year the contraceptive pill became available, and has been on a gradual decline ever since.

It hit a record low of 1.59 in 2020 before increasing to 1.7 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

At the same time, the average age of first-time mothers has steadily increased.

In 1961 and 1971, nearly half of first-time mothers were aged 20 to 24. By 2020, that number was 14 per cent. The percentage of women having their first child at 30 or older has increased from 15 per cent before 1981 to 53 per cent in 2020.

“The fertility rates of those aged in their thirties have mostly increased since the early 1980s, while the fertility rates for women in their twenties has continued to fall,” the AIFS says.

“This reflects the trend of women delaying having a first child. The fall in the fertility rates for those in their teens and twenties has also been influenced by social changes such as increased participation in formal schooling and tertiary education by young people, women’s increased labour force participation, and changes in family-related values and attitudes.”

‘People aren’t stupid’

Dr Bob Birrell, president of The Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI), says there is a grim irony in the fact that immigration is posed as the solution to falling birthrates, when it may be contributing to the problem.

“It is important to increase fertility, and to do that we’ve got to provide affordable, family-friendly housing,” he said.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt that the reason fertility has dropped way below replacement is because we aren’t creating the circumstances, including family-friendly housing, that would facilitate young couples making the decision to have children.”

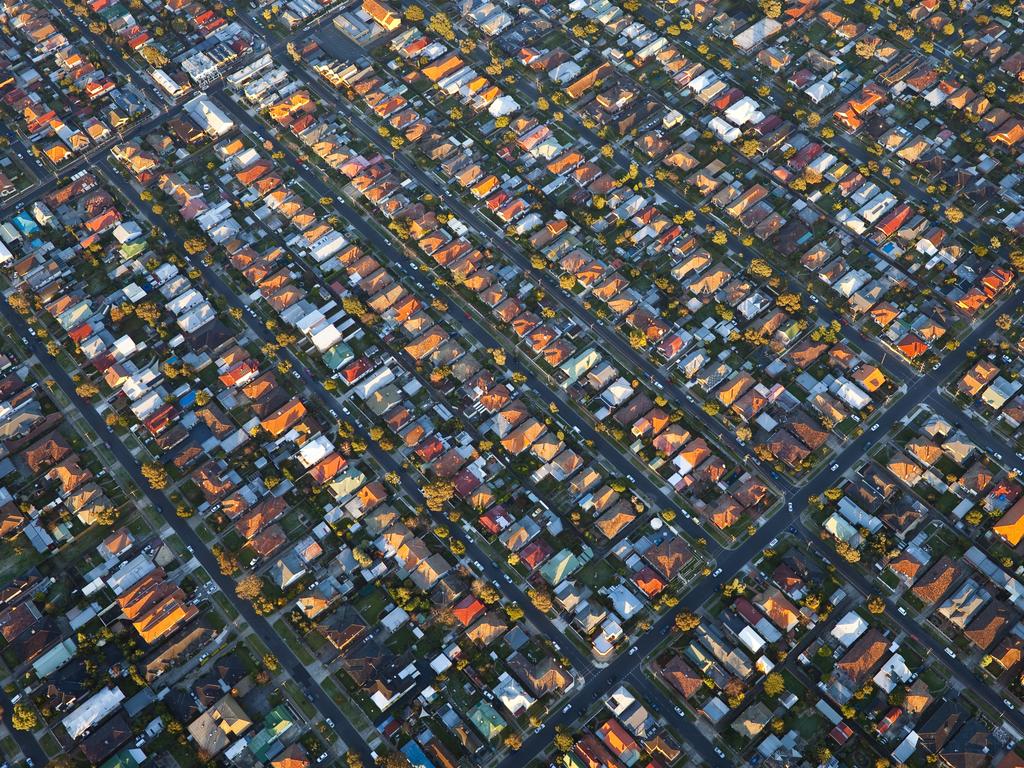

Housing affordability in Australia hit a three-decade low this year, according to PropTrack, driven by a sharp rise in mortgage rates and increasing home prices. The situation for renters is equally dire.

“We’re seeing a massive increase in housing affordability problems coinciding with this surge in migration,” Dr Birrell said.

“There’s a direct link, I think most people can see that — they’re not stupid.”

The PropTrack Housing Affordability Index, published in September, found households earning the median income of $105,000 could afford just 13 per cent of homes sold in the past year — the smallest share since 1995.

A low-income household earning $64,000 could afford just 3 per cent of homes.

And servicing a mortgage was close to as hard as it has ever been, just below the peak reached in 1989, the report found. A household earning average income would need to spend a third of their income on mortgage repayments to buy a median-priced home.

Affordability was the worst in NSW — where a typical income could afford just 7 per cent of homes — Tasmania and Victoria.

The same factors driving decreased affordability have also reduced housing accessibility — the amount of time it takes new buyers to save a deposit.

The average household would need to save 20 per cent of their income for more than five-and-a-half years to save a 20 per cent deposit on a median-priced home, according to PropTrack.

In 1990, that figure was less than three years, and just over two years in the prior decade.

“Surging home prices throughout the pandemic and rapidly rising interest rates over the past year have brought housing affordability to its worst level in at least three decades,” PropTrack senior economist Angus Moore said.

“The situation is especially challenging for lower-income households and first-home buyers.”

‘Go back to the 1950s’

Professor James Raymer from the ANU’s School of Demography disagreed that housing affordability was hurting fertility rates.

“I wouldn’t say that’s the reason,” he said.

“I’d say the reason is postponement — education, career progression, society is telling everyone, not just women, to get their education, get a good job then buy a house, and by the time you can do all these things you’re in your 30s and there’s just not enough time to have more than two kids.”

Prof Raymer said migration was only a “short-term fix” to temporarily offset a problem that was affecting most of the world aside from the poorest countries.

“China is even more worrying because of its size — there are not enough migrants in the world that could offset the decline they’re facing,” he said.

“The solution is hard. I don’t know if any demographers are optimistic about populations going back to having three or four kids per woman, because we’ve headed down this road where we think it’s important that women have autonomy, have a good education, good career prospects, should be highly skilled. All that leads to this idea that you shouldn’t have children when you’re young, and it seems that’s the way we’re going to stay.”

Prof Raymer said the “easy solution” would be to “go back to how things were in the 1950s”, with single-income households, stay-at-home mothers and couples having children in their early 20s.

“No one wants to do that,” he said. “Could you encourage people to have kids in their 20s these days? I wouldn’t want my kids to do that.”

46 million Australians

With debate over immigration levels raging, forecasts released by the ABS last week suggested Australia’s population could reach 46 million by 2071 — a 77 per cent increase in just under five decades.

The stark figure, which represents a 77 per cent gain in population in the space of 48 years, is the top end of the ABS’ population forecast.

The “medium” prediction shows the population hitting nearly 40 million by 2071, while the low-end forecast still shows a 30 per cent increase in population from about 26 million in 2023 to 34.3 million in the early 2070s.

The bulge in numbers is driven primarily by an expected endless migration boom.

In a high-end estimate, the ABS expects immigrants to add 14.3 million to the population, with a yearly intake of about 275,000 people.

The middle forecast puts the migration contribution at 11.8 million, with an annual increase of 225,000 people, while the low-end estimate is 175,000 new arrivals each year adding 9.4 million to the population.

The ABS suggests without immigration, Australia’s population would shrink in size due to low birth rates, with all scenarios envisioning a birthrate below the replacement rate of 2.1 per cent.

Without migrants, the ABS states Australia’s population would fall to 23.9 million by 2071 — a decline of more than two million people from 2023 levels.

Voters want migration cuts

It comes after a survey published in Nine Newspapers over the weekend suggested a clear majority of Australians want the federal government to cut migration to “sustainable” levels.

The Resolve Political Monitor poll of 1605 people found 62 per cent of voters said the current intake is too high, while only 16 per cent believe the government is running the migration program in a carefully planned and managed way.

“It’s most unusual for them to ask a specific set of questions about migration,” Dr Birrell said. “It’s quite significant that they have asked the question and they’ve reported the results.”

Polls conducted by TAPRI have consistently found 60 to 70 per cent of Australian voters want vastly reduced immigration, with respondents commonly citing congestion and overcrowding, pressure on hospitals, the effect on the environment and increasing cost of housing.

“We’ve been able to show for years that most people don’t like the Big Australia migration policy, but it has had little or no influence [on governments] — but that’s changing now,” Dr Birrell said.

“Immigration has suddenly become an issue right across the advanced world and it’s having real political consequences. It’s partly the economic situation. People are not happy.”

Dr Birrell agreed that “yes we’ve got to do something” about the ageing population and labour shortages, but it was used as an “excuse” to cover for a poorly managed migration program.

“For a start we need to train more of our own people to fill the engineering, IT and professional fields, but also the construction workforce,” he said.

“We’re training more overseas students in IT and engineering than we are domestic students. And our apprentice levels in the construction trades are really low, which is why construction employers are crying out for more migrants but we’re not getting skilled tradespeople. Very few are coming by permanent or temporary entry programs and overseas students who might like to become plumbers and electricians are not permitted. There’s only one way to fix that at the moment and that’s to increase the level of apprenticeships.”

Labor changes a ‘nothingburger’

On Monday, Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil announced tougher rules on international students as part of the government’s sweeping migration system overhaul.

Ms O’Neil said the system had been “deliberately neglected over a decade” and pledged to close backdoors that allowed people to “visa jump” and attend “ghost colleges” while pathways for much-needed highly skilled migrants remained convoluted and time consuming.

MacroBusiness chief economist Leith van Onselen labelled the reforms a “nothingburger”.

“Basically, what they’ve announced is a knee-jerk reaction to their poor polling,” he told 2GB.

“Australians are pretty unhappy about this mass immigration. We’ve had record numbers, we’ve obviously got a rental crisis, all that sort of thing. And what Albo basically came out and said is, look we’re going to reduce it to a ‘sustainable level’. But they’re not. Basically, they’ve still left the permanent migrant intake at a record high 210,000 if you include the humanitarian intake. They’ve also left the temporary visa system uncapped and demand-driven.”

Mr van Onselen argued that “effectively, all they’re doing is they said they’re going to slightly tighten student visas to stop them from going into low-quality courses and crackdown on dodgy colleges”.

More Coverage

“It seems that ‘sustainable immigration’ … means a level of 250,000-plus, which is way above what we had pre-pandemic, or what the 2001 Intergenerational Report said, which was only 90,000 net overseas migration a year,” he said.

— with NCA NewsWire