When Richard Pusey sped his Porsche 911 down the Eastern Freeway at lightning speed it set off a chain of events that would lead to the biggest loss of police lives since the time of Ned Kelly.

Speed kills. Richard Pusey found that out the hard way when four police officers were killed after they stopped him for driving his Porsche insanely fast.

The cashed-up, drug-fuelled mortgage broker had earlier boasted of doing up to 300kmh on the Eastern Freeway, which he used as a racetrack until it all went wrong.

The tragedy of drug abuse on and off the roads is that the innocent often lose their lives because of the actions of the guilty. As someone said after another fatal crash that killed a brilliant scientist “meth can destroy your life even if you’ve never touched it.”

When news of the Eastern Freeway deaths broke late on Wednesday, April 22, those who knew Pusey were no doubt shocked at the scale of the carnage when a semi-trailer veered across the freeway and hit four police. But they could hardly be totally surprised at his involvement.

‘A NUTTER’ BOUND FOR TROUBLE

To know Pusey was to know he was trouble. Even two decades before he was caught driving at criminally reckless speeds and a slew of other offences, the signs were clear that he had an anti-social streak a courtroom psychologist couldn’t jump over.

As far back as 1999, fellow workers at the Malvern Tram Depot realised the young Pusey was a crash waiting to happen. That’s why their manager decided to get rid of him after trying to help him, and being rebuffed by the arrogant and angry young man.

The manager, a former tram driver, understood the frustrations that drivers faced in dealing with the public and other traffic.

But he soon decided that Pusey, though intelligent, was “a nutter who couldn’t get through life without getting into trouble.”

“I knew he was a problem before I got there as the previous manager would have told me,” he told the Herald Sun.

“He had an excuse for everything. Nothing was ever his fault.”

In the last few weeks of that year and early in the new one, Pusey had caused so many passenger complaints that the tramways management approved a simple undercover operation to test the claims and gather evidence.

They called in an outside instructor from East Hawthorn depot to board Pusey’s tram in plain clothes and watch how he behaved with the public and at the controls.

Pusey drove aggressively and fast and was rude to passengers who complained, all of which the inspector put in a written report.

It was clear that passengers who’d made complaints about Pusey’s risk-taking behaviour were not exaggerating. He was running off the rails.

The disciplinary panel appointed to judge Pusey’s behaviour and decide his future included a union representative who would normally fight hard for members in trouble. But even the loyal union “rep” could not raise valid reasons to stop Pusey being sacked.

He had, after all, committed an offence for which no tram driver is forgiven barring exceptional circumstances: one day, annoyed that a relief driver had not been at the usual “take point” where drivers switch trams, he had simply abandoned his tram and walked off.

In that situation, normal drivers continued along the route and changed at the next “take point”. But Pusey wasn’t normal.

He left his passengers stranded on the tram at the corner of Wattle Tree and Glenferrie Rds and walked to the depot. For no better reason than he felt like it.

That act was an insight into an unnaturally selfish personality, says the man who sacked him. But it wasn’t the only one.

When Pusey received his termination letter, he stormed into the manager’s office and spoke threateningly to the clerk.

When she told him the manager was out, he snarled that he was going home “to get a gun” — and that he would come back to “get” the manager.

The clerk asked him to leave and immediately called her boss to warn him. He reported Pusey’s threat to Malvern Police. He went to the station and made a statement to a sergeant but never heard any more about it.

A woman believed to be Pusey’s mother telephoned the depot to launch a furious attack on those who had the nerve to sack her son.

A DISTRAUGHT MOTHER, AN ESTRANGED SON

One thing that would change in the next 20 years was that Pusey’s family stopped defending his increasingly bizarre behaviour, at least publicly.

Days after the freeway crash in April, Pusey’s mother called Neil Mitchell’s current affairs program on 3AW and asked to broadcast a message from the family.

She made it clear she was speaking on behalf of the family to avoid public speculation and media questions about her son’s background, and to disassociate family members from his behaviour.

She then read out a long written statement stressing how anguished and disgusted the family were, suggesting Pusey was estranged from them.

It was all the unfortunate woman could do in the circumstances. It was far too late to do anything about the strange and unpleasant man who had gone from tram driver to nurse to millionaire mortgage broker to defiant pariah to frightened prisoner.

One whose actions not only derailed his own life but led to the violent deaths of four decent people.

Not that Pusey actually killed them, of course. Their deaths, whether accidental or criminal, were caused by another driver. A man with little in common with Richard Pusey except for something that links both of them with tens of thousands of Australians: the use of amphetamines.

Speed kills, even if you’ve never touched the stuff.

FOUR LONG ROADS TO TRAGEDY

The average life is a series of chance events that barely fill a few minutes but which dictate destinies. The Hollywood shorthand for this is “Sliding Doors moments”.

Where does it start, the chain of events leading four police officers to the south side of the Eastern Freeway in Balwyn North late on the afternoon of April 22?

For Leading Sen. Const. Lynette Taylor, it began 31 years ago, when she made a life-changing decision to join the police force. She was 29, and already had experience working in the wider world.

Her pleasant personality was already formed when she graduated from the Police Academy, and everything from her hair style to her dress sense was a little less conservative than some of her contemporaries.

Which is why she caught the eye of fellow officer Stuart Schulze.

As Stuart would tell their two sons and family and friends much later, his future wife was the only person wearing a dress in the police club, in those days still in the building behind Russell St police station. And Lynette’s was not just any dress — it was a “hippy” model to go with her happy outlook.

The couple didn’t just build a family. They built an ocean-going yacht, Sapphire Blue, that was so seaworthy that they took the trip of a lifetime: a year spent cruising in the South Pacific.

No wonder Lynette Taylor came across as one of the most cheerful of the older officers in her job with the Road Policing Drug and Alcohol operations section, where she deftly steered nervous or overconfident rookies through their first few months on the job.

Among the “newbies” who appreciated Lynette Taylor’s disposition and practical wisdom was Josh Prestney, who had joined the force at 28.

Josh’s younger brother Alex, came to police work first. It was Alex who presented big brother Josh, just 18 months older, with his badge when he graduated from the academy in December 2019. Their parents, Andrew and Belinda Prestney, could not have known which son they were proudest of that day.

Early last year, the brothers ended up briefly stationed together at the Boroondara station in Harp Rd, Kew, before Alex moved on to his next posting.

Workmates would joke with Josh, asking him where “the good Prestney” was. The truth was that the brothers were hard to split. They were both good.

The police policy of recruiting people with life experience was paying dividends, which was obvious when Glen Humphris had turned up from NSW.

Const. Humphris joined “the job” in 2019, the last staging post in a varied career. The Gosford-born Humphris worked as a carpenter when he left school but he changed directions, and became a personal trainer before studying exercise and sports science at Newcastle then at the University of Sydney.

The turning point came after he met his life partner, Todd Robinson, who shared his enthusiasm for long runs, bike rides and triathlons. When Todd joined the army and was posted to Melbourne, Glen took the plunge and joined the Victoria Police so they could share a new life together in a new state.

He chose the “blue” uniform ahead of the green military one because he wanted to help people. He liked it, and was good at it. Right up until the shift that began at 9am on April 22.

“He loved it,” recalls Todd.

“Glen just loved helping people, being there if someone was in trouble.”

Sen. Const. Kevin King, a family man, joined the force in his 40s after half a lifetime in the clothing industry. He did six years at various stations around Melbourne before being transferred to Nunawading Highway Patrol in 2018.

After his wife, Sharron, and their three teenage boys, Kevin King loved Richmond Football Club and his new career as a policeman. He turned 50 in February last year. He was known as a kind man, a good example for younger members.

On April 22, Glen teamed up with Lynette Taylor to do their 10-hour shift. Each arrived at the traffic branch at Dawson St, Brunswick, at 9am ready to work until 7pm.

Later in the day, Josh Prestney said goodbye to his partner Stacey and drove to Nunawading, where he had recently been posted with the road patrol. On that Wednesday, he was directed to work with Kevin King, who knew the ropes. Their shift started at 3pm.

Normal heavy commuter traffic — the pre-Covid pandemic sort — is frustrating for drivers but it keeps speeds down. But, because of the pandemic, the freeways and main arterial roads were noticeably less choked with traffic, so much so that older police commented on how similar it was to working in the 1970s and 1980s.

But relatively empty roads and the slightly surreal atmosphere caused by the pandemic triggers opportunistic behaviour in the troublesome few — especially idiots who crave extreme speed.

For police who patrol the roads, their job is like parachuting: safe enough right up until the moment you open the door and step into the unknown.

Statistically, it’s not bullets, bombs and knives that kill those we pay to wear the badge in Australia. It is traffic.

‘WHAT IFS’ HAUNT LOVED ONES

Life’s sliding doors open and shut with sometimes fatal precision.

Change even a minute leading into the collision on the afternoon of April 22 — and it wouldn’t have happened. Any tiny delay would have altered unfolding events, which is why “What ifs” haunt and taunt those who lose loved ones.

Lynette Taylor and Glen Humphris happen to be patrolling the freeway, inbound, at exactly the right time to see a black 911 Porsche weaving through traffic at up to 149kmh.

They intercept the Porsche west of Burke Rd at 4.51pm. The driver parks in the emergency lane. This is the Hays Paddock part of Kew East, opposite Ivanhoe golf course.

The driver is 41-year-old Richard Paul Pusey. His behaviour suggests he is affected by drugs or alcohol.

Checks show he is well-known to police. After a preliminary breath test, they take a mouth swab. It is positive for two drugs.

The combination of high speed and drug use triggers a routine response: impound the car. Which means calling in the highway patrol, whose members are expert at the complicated business of impounding vehicles. It all takes time.

So far, so normal, apart from the agitated behaviour of the Porsche driver. By the time the highway patrol car arrives at 5.35pm, with Kevin King and Josh Prestney aboard, he is seething.

The four police confer, standing together near their cars. Pusey, all inhibitions gone, stalks to the guard rail next to the verge and urinates.

That minute of gross behaviour saves his life.

DRIVER FELL THROUGH THE CRACKS

The long and winding road that led Mohinder Singh Bajwa to the short and relatively straight Eastern Freeway that day began in southern NSW in his teens.

In the 1970s, “Sergi” had been the most common surname around Griffith, with more than 300 Sergis on electoral rolls. That list included many good citizens and some bad ones, including the “godfather” of the Calabrian mafia cell that plotted to murder local businessman Don Mackay in 1977 for opposing the cannabis trade.

By the 1990s, the name “Singh” had overtaken Sergi around Griffith as waves of Indians arrived, first as farm workers, then growers and contractors.

The Sikh settlers bought up former soldier settler properties known as “fruit salad” blocks because the owners grew a mixture of fruit and vegetables, and sometimes “a crop”, as in marijuana.

As happens with first generation migrants, Mohinder Singh Bajwa grew away from the conservative beliefs of his elders, took up some “Aussie” attributes.

No turban or beard for him; he was more tattoos, ear ring and shorts, fitting in with the “skips” and islanders who graduated from fruit picking to driving forklifts and trucks in the buzzing agricultural industry.

Mohinder Singh moved up to driving semi-trailers, then left Griffith’s tight knit Indian community for Melbourne. He apparently picked up some other habits on the way. One, allegedly, was using methamphetamines, drug of choice for fatigued truck drivers.

That is the most feasible explanation for the “ice pipe” in the cabin of the Volvo prime mover he was driving on April 22, hauling a refrigerated trailer of poultry meat for his employer, Connect Logistics.

He was by some accounts not fit to be driving at all, let alone on that day.

Subsequent investigations suggested his mental state was unstable enough that others had noticed. Somehow, he fell through the cracks in a business of tight deadlines and tighter margins.

While the Volvo semi-trailer is heading west the four police officers are plodding through the necessary motions of impounding Pusey’s Porsche.

The act of taking someone’s car is simple enough at one level: grab the keys and drive off. That’s what a carjacker would do, or a repossession agent.

But the modern police force rarely uses force. Impounding a car is unavoidably laborious, especially when dealing with an extremely expensive vehicle owned, by definition, by someone with the clout to cause repercussions.

The aftermath of the interception took a long time. Under normal conditions it could easily have ended up taking an hour or more before a tow truck winched the Porsche on board.

As it was, it was 50 minutes from the time Pusey was stopped until the semi-trailer approached from the east. A long time to be stuck beside freeway traffic in poor light.

The four officers were standing on the road side of their cars when the truck veered across the freeway and into the emergency lane at 5.42pm.

What happened next has been stated in excruciating detail too often, and will be again in court. The three men were killed virtually outright. Lynette Taylor was terribly injured and crying for help.

FROM NOBODY TO MOST REVILED MAN IN AUSTRALIA

If a person’s worth is their reaction to the plight of fellow humans, Richard Pusey failed completely.

He used a mobile phone to film the policewoman’s dying moments. That was shocking enough. But what he said, recorded by her body camera, linked him forever to Victoria’s worst police fatality.

He said: “There you go. Amazing, absolutely amazing. All I wanted was to go home and have my sushi and now you’ve f … ed my f … ing car.” Then he spoke to a witness who stopped, saying: “That’s my f … ing car, mate”. Then he hitched a ride home to Fitzroy.

In a few minutes of grotesque behaviour, Pusey had made himself a figure of hatred and contempt.

So much so that it was easy to believe whatever was said about him: such as the story that he had posted footage of the dying policewoman online. In fact, he did not, though he had passed it to a third party.

On the way from the crash scene Pusey called his wife and told her what had happened. He also spoke to his doctor about it, and to police officers he knows.

Late that night, Pusey told local police he wasn’t well enough to see them then. By the time he turned up to West Melbourne police station with a lawyer the next morning, he was the most reviled man in Australia.

This would explain why a posse of eight detectives turned up with a warrant to his $3.2 million converted warehouse in Fitzroy.

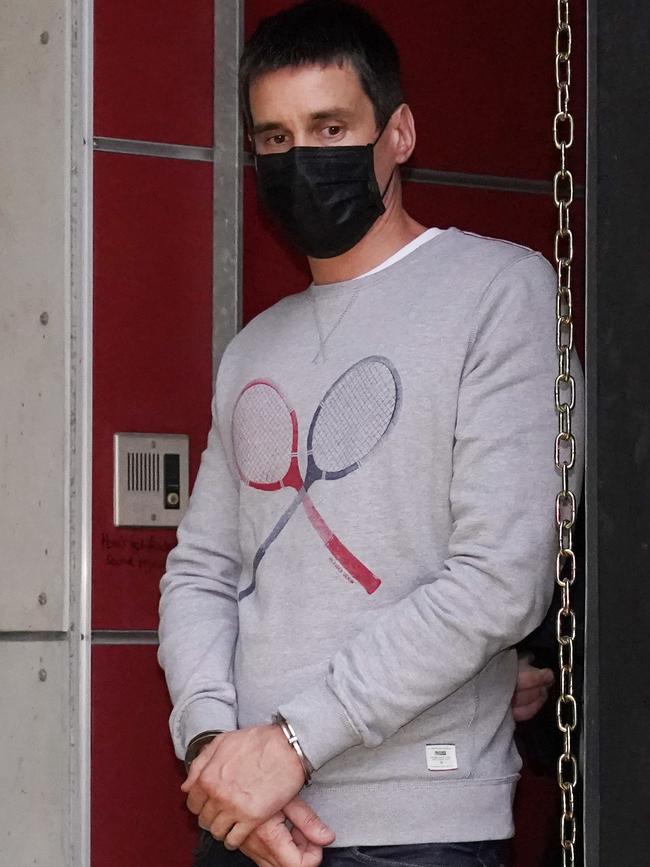

He was formally arrested at 2.50pm and brought out handcuffed to face media cameras outside his fortified building. Police seized an iPhone and a small amount of methamphetamine.

In court next morning, Pusey’s lawyer said he had mental problems. He had been charged with nine offences including driving at a dangerous speed, reckless conduct endangering life, failing to render assistance and drug possession.

He was also charged with destroying evidence, failing to remain after a drug test, failing to exchange details and committing an indictable offence while on bail.

Meanwhile, under guard in hospital, the man who actually caused the deaths — the one who might or might not be guilty of manslaughter or culpable driving or merely carelessness — was not going well. He had been deranged and inconsolable at the crash scene, raving incoherently before collapsing.

It wasn’t until Sunday, April 26, that Mohinder Singh was charged with four counts of culpable driving. His behaviour gave the impression of someone with psychological problems, drug problems or both.

At some point he said he’d seen “a witch” on the road.

ONE-IN-A-MILLION COINCIDENCE FUELS RUMOUR MILL

The police rumour mill moved into overdrive. Police command’s strong but short-lived belief that Pusey had posted gruesome footage online was trumped by a story that the semi-trailer driver had staged murder-by-truck.

The fact that he was Indian implied to some that he was a radical Muslim staging a “lone wolf” attack.

That rumour that gained traction in the first 24 hours, as serving and retired police around Australia circulated a story among themselves that the truck driver had taken revenge after being pulled over and fined earlier.

The revenge motive seemed plausible because it would add some logic to carnage that seemed too terrible to be random.

But being plausible did not make it true.

Mohinder Singh is a Sikh, not a radical Muslim, and apparently had not had any interaction with police for some time.

Yet his semi-trailer had veered across three lanes at precisely the spot where two police cars were parked, emergency lights blazing.

In the immediate aftermath, some found it hard to comprehend because it seemed a one-in-a-million coincidence.

But perhaps it wasn’t a coincidence at all: a plausible explanation is that Singh’s reactions and concentration were impaired by fatigue or delusions or a telephone, so that when traffic ahead slowed suddenly to pass the Porsche and police cars, he saw it too late and swung hard left to avoid hitting a queue of cars.

That would place the truck in the emergency lane at close to full speed. Anyone who drives regularly on freeways knows that when police vehicles are beside the road, the instinct to “rubberneck” causes car drivers to brake, despite the risk of being tail-ended.

That scenario might explain the question: “Why did he swerve then and there?”

A court, of course, will try to sort fact from speculation.

But in the days after the collision, the court of public opinion ran on raw emotion — most of it caused by Pusey’s actions. He had become the focus of anger and grief. Everything emerging about him painted a picture of the Devil driving a Porsche.

Within 48 hours, reporters had unearthed a backstory that portrayed someone between unpleasant and unhinged, narcissistic and nasty.

Exhibit A was a video clip of Pusey screaming obscenities at a woman with breast cancer, telling her she was going to die — this during one of the serial disputes he had.

At the time of the crash he was on bail for an assault charge scheduled to be heard in court on April 30 last year, and one of criminal damage set for June 16.

He had a dozen previous charges, beginning in 2007 when he was fined for speeding 70kmh over the limit. The following year he was jailed for eight months, half of it suspended, and ordered to pay compensation for an injury.

In 2014, he was convicted and fined $2000 and $2500 costs for building without a permit. Two years later, he was ordered to do 60 hours community service for stalking.

In 2017, he was fined $500 for breaching an intervention order, $200 for driving while suspended and $500 for excessive noise at his house.

He was later convicted and fined $750 for using a carriage service to menace. He had disputes with tradesmen over a 2014 kitchen rebuild that ended up in the Supreme Court.

When sued for not paying $6006, he made a counterclaim for $35,500, claiming the kitchen was “defective”. His claim was thrown out as an “abuse of process”.

All the while, he was brokering mortgages and trading properties. He sold a historic building in the CBD for $4.4 million in September 2019, after buying it in 2017 for $2.8 million. But money didn’t seem to help his character flaws.

There was the story of his dispute with Whitehorse City Council over the height of a fence at a house he owned, of how he intimidated council staff with abuse and threats. He sent 19 email rants — in three languages — to the council in four days. On and on it goes, a checklist of sociopathic behaviour.

As any police or ambulance officer knows, the week between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Day often triggers the worst in people: ordinary people can become very “ordinary” indeed, let alone those with ingrained psychological kinks.

So it was hardly a shock that critical incident response police were called to a Fitzroy property late on Sunday, December 27, after reports of screaming and smashed windows. Police forced entry and found a man on the roof. The man was Richard Pusey.

He was taken to hospital for assessment and later charged for an alleged assault, making threats to kill, false imprisonment, using a telecommunication service to harass, contravening bail conditions and committing an indictable offence while on bail. A specific allegation is that he placed a noose around a woman’s neck.

None of which would surprise the people who’d worked with the cocky 20-year-old at Malvern tram depot in 1999.

Leopards don’t change their spots and neither do hyenas.

Northland back in lockdown for second time in 24-hours

Northland shopping centre has been put back into lockdown on Thursday morning — the latest drama coming after a man was arrested after a stolen Toyota LandCruiser tore through the centre on Wednesday afternoon.

Youth crime up 18 per cent over past year, arrests at record high

Offending by children surged 18 per cent in the year to March as Victoria Police carried out the most arrests ever in its 172-year history.