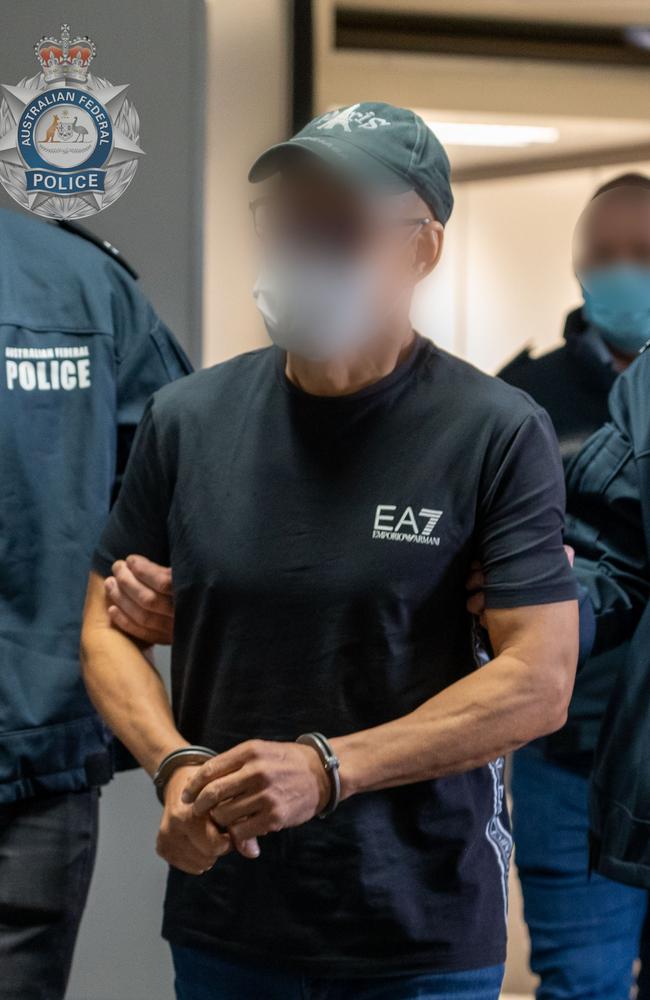

How AFP unmasked The Company and its alleged ringleaders Chung Chak Lee and Chi Lop Tse

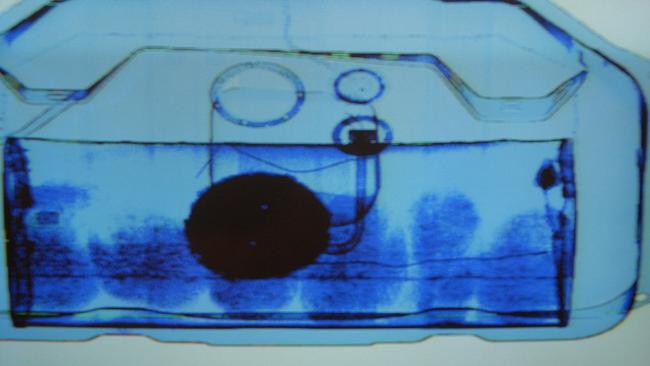

This is how a seizure of an iPhone and an x-ray led the AFP to the world’s biggest drug cartel which is accused of selling drugs that end up on Australian streets.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They were six words which changed everything: “F–––, I know who you are!’”

It was the moment when an eagle eyed Australian Federal Police officer unmasked the world’s biggest drug cartel.

The overseas-based Aussie cop had been invited to look at an Aladdin’s Cave of photographs, seized from two iPhones found on a fidgety, drug mule with blistered hands at Yangon Airport, in Myanmar.

Police in more than 20 countries had been hunting for the head of a drug operation that would eventually become known as The Company, or Sam Gor cartel.

But now they had the name and image of its leader and proof of extensive drug operations – all contained in time stamped, geolocated photographs on the drug mule’s phones.

The images were crucial pieces of a puzzle that revealed Asian triads were linked as one cartel.

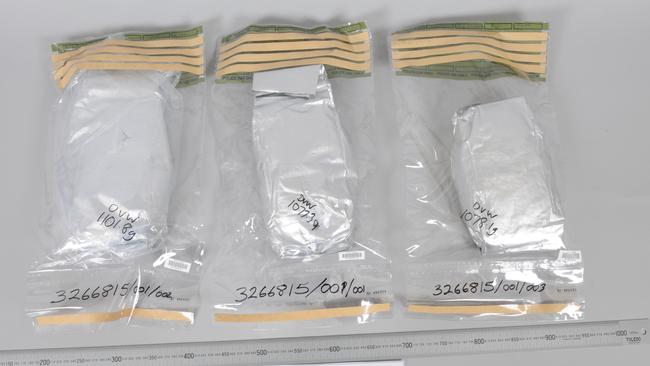

Now police could take down the puppet masters who control the rivers of ice, heroin and ecstasy flooding Australia, usually trafficked in packets of loose leaf tea.

IN THE SHADOWS

The Company rarely makes headlines, laying low is part of its business model.

You have probably never heard of them. But when the tattooed bikies from the Hells Angels and Comancheros sell drugs on Australia’s streets, seven times out of 10, it’s probably supplied by The Company from their super labs in the Golden Triangle, the lawless part of Myanmar that borders Thailand, Laos and China.

And when your neighbour, relative or friend spirals from a reliable, happy person to an ice addict shooting up on the street outside a railway station, begging for change, there is a good chance their habit has been fed by The Company, police allege.

Their drug profits have also tainted Australia’s business community, with The Company laundering millions through Crown Casino, leading to major inquiries and restrictions on its licence.

But a decade-long international sting, led by the Australian Federal Police, is bringing The Company out of the shadows and its accused ringleaders to justice Down Under.

The extradition of Chung Chak Lee to Australia on Saturday is a watershed moment in the fight against drugs and the misery they are causing in Australia, particularly in regional and rural communities.

Lee, 66, was number six on an AFP target list – an alleged big fish that the AFP has wanted to get on the hook since he was linked to 42kg of drugs seized in 2012.

His alleged boss, Chi Lop Tse, 57, is next to come back. His return would be even more significant.

Tse managed to get five warring Asian triads – 14K, the Big Circle Gang, the Bamboo Union, Sun Yee On and Wo Shing Wo triads – to come together to form The Company.

They now turn over $23 billion each year – that’s more than the size of Albania or Mozambique’s economy – with a chunk of their profits coming from Australia where ice sells wholesale for up to $300,000 a kilogram.

Tse, the AFP’s number one target who was arrested in 2021, lost an appeal against extradition to Australia in the Netherlands this week. His lawyers had demanded that Australia guarantee he would not be given a life sentence without parole if he was sent to face court here. Now he’s waiting on the Dutch Justice Minister to decide his fate.

Tse, stuck in maximum security in a Dutch jail, is a long way from the Macau casinos, where he lost $90 million in one night.

Lee, who was alleged to be Tse’s senior associate, was arrested a few months before his alleged boss.

The Hong Kong resident had been living in Bangkok.

Diligent detective work from AFP officers stationed in Thailand uncovered his location in March 2020. They found his apartment and Royal Thai Police arrested him in October 2020.

THE BREAKTHROUGH

The Company’s top brass had been elusive.

Tse and Lee may never have been caught but crime fighters had a stroke of luck with the capture of a drug mule who took too many photographs on his mobile phone.

Jeng Ze Cai was arrested at Yangon Airport in Myanmar on November 15, 2016.

He wanted to travel home to Taiwan, but he was picked up by airport police who noticed he was nervous, and spotted his blistered hands.

When they searched him they found 80 grams of party drug ketamine strapped to his thighs.

Police found videos on his phone as well as hundreds of photographs, thousands of calls and text messages.

Investigators saw one video that showed a terrified man, who was tied up while three men used a blowtorch on his feet.

To give him a break, they would blast him with an electric cattle prod.

The video was a warning – the blowtorched drug courier had thrown 300kg of meth overboard thinking he was about to get raided by water patrol cops. The Company doesn’t like mistakes.

Cai never talked, but the pictures on his phone told a thousand words.

He had been travelling around doing The Company’s dirty work for months, chronicling everything on two iPhones.

The Australian Federal Police, which have good relationships with their Myanmar counterparts, were brought into the fold. They were invited to inspect the photographs and text messages. Among the photographs found on Cai’s phone was an image of Chi Lop Tse.

“This one stuck out because it was Canadian. I said: ‘F---, I know who you are!’”, an AFP officer based in Asia told Reuters.

That moment in 2016 gave police alleged connections to the cartel they had been chasing for years.

It also revealed that the drug shipments, which appeared to be random, were actually linked – it was one group running the show.

Buried in the Australian Federal Police’s 2013 annual report is a reference to Operation Volante.

It was described as “a joint operation involving the AFP, Victoria Police, NSW Police, the ACC and (Customs) which targeted an international organised criminal syndicate operating across five countries and importing heroin and methamphetamine into Australia. A total of 27 people were arrested and more than 42 kilograms of drugs were confiscated.”

Australian authorities always suspected that the raid was just scratching the surface of organised crime. They were right.

But now they had some evidence.

The key was turning that photograph into an x-ray of the skeleton of The Company.

STRANGE EVIDENCE

Police often refer to The Company as Sam Gor, in a nod to Tse’s nickname, which translates to Brother Number Three, because of his influential role.

The arrest of Lee in Thailand, who was picked up first, was proof of how important it is to have Australian police on the ground across the world. Around the same time, the AFP had discovered Tse was hiding in Taiwan. The billionaire drug lord was nabbed when he was travelling back to Canada in January 2021, where he had previously lived, just a few months after Lee’s arrest.

The Dutch authorities were tipped off and Tse was arrested at the airport while in transit.

The arrests of both men were just the start of the process of getting them to Australia to face court.

Lee’s arrival in Melbourne will potentially open a Pandora’s box of evidence about the scale of The Company’s operations in Australia.

But there were breadcrumbs of The Company’s influence being trailed through Australia’s courts over the past decade.

Operation Volante picked up some strange evidence.

There was $5 million worth of property seized and $4 million in cash. That’s to be expected, but perhaps not at such a scale.

Police found 99 designer handbags and jewellery worth $1.5 million.

The odd discovery was $600,000 worth of Crown Casino chips.

Those chips would ultimately lead to a major review of Crown, with three separate inquiries on whether it was fit to hold a gaming licence and led to James Packer selling off his shares in the group.

Operation Volante tipped police off to how The Company was bankrolling Chinese gamblers here and then collecting the money in transfers between Chinese banks.

Whye Wah Moo, or Roy Moo, was sentenced to two years’ jail in Victoria’s County Court in 2013 over money laundering.

The Bergin report in NSW into whether Crown should was fit to have a licence for its yet to be opened Barangaroo casino put the link between the drug cartel and the casino in black and white.

“There is no doubt that the money laundered by Roy Moo came from the proceeds of criminal activity by the international drug trafficking syndicate, The Company,” the Bergin inquiry’s report stated. “There is no doubt that the money was laundered through Crown Melbourne.”

Lee also came up in the court case of Suky Lieu, a Melbourne green grocer now serving 25 years for commercial drug trafficking.

Publicly available documents from Lieu’s appeal claim that a man named John was organising his money laundering from overseas. John was one of Lee’s nicknames.

‘IT’S NOT OVER YET’

The AFP was not going to let The Company off the hook and they headed up Operation Kungur – a new front in the fight against organised crime. The team of Operation Kungur included at least 20 law enforcement agencies across the world. Tse was the main target of that operation.

A branch of that investigation Operation Kungur-Oak resulted in the arrest and conviction of four Melbourne men, who were nabbed moving drugs around the city’s western suburbs.

They were convicted of dealing with $1.9 million described as “proceeds of crime”, which was allegedly the cartel’s cash.

The Company was also linked to the seizure of $1 billion worth of ice in Geraldton, Western Australia in 2017.

The threads of the 10-year investigation into The Company came together on Saturday, with Lee’s extradition.

The AFP declined interviews and requests for comment for this story.

But in 2013, the AFP’s manager of serious and organised crime, then Commander David Sharpe, was emphatic about the significance of the arrests at the time.

“This investigation was about following the money trails, removing the wealth and cutting of distribution networks in Australia and internationally,” he said at the time.

“This investigation is not over.

“It continues across Australia and internationally and further arrests will be made.”

Sharpe, who is now chief executive of Sport Integrity Australia, made a point of highlighting the flash cars, allegedly bought with stolen money, that were seized.

“While these people are driving around in Lamborghinis … and living their life of luxury as rock stars, the impacts of the drugs their selling is in the hospitals in the emergency wards and splitting the families,” he said.

“It’s quite satisfying when you see these people live this sort of lifestyle but then when you see them in tears when the handcuffs go on and their Lamborghini is on the back of a truck being taken away.”

The next chapter will play out in Melbourne’s courts, a decade on from those first arrests.