George Marrogi: The baby faced Year 7 who loved maths, to feared boss of Notorious Crime Family

Authorities had hoped George Marrogi could live a law-abiding life, but once he had uncorked years of bottled rage there was no turning back.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

George Marrogi barely reacted when he was sentenced to 32 years’ jail for the murder of Kadir Ors.

Justice Paul Coughlan said Marrogi’s “lawless” actions were “one of the most blatant examples of murder” he had seen.

But this wasn’t Marrogi’s first rodeo.

By 34, he had spent most of his adult life in prison.

Perplexingly, prison authorities thought he was a model inmate, but whenever he was set free, he would revert to the lawlessness which had typified his life since he was a young man.

The judges, lawyers and psychologists tasked with solving the riddle of Marrogi still hold out hope he might one day live a law-abiding life.

But looking at Marrogi’s life, it’s a remarkable level of optimism.

These days, the crime boss spends his days locked up like a caged animal at Barwon Prison, where he flits between maximum security and solitary confinement.

He will be an old man by the time he gets a chance at freedom.

But unlike most of the men who have ruled Melbourne’s underworld, Marrogi’s early years remain largely shrouded in mystery.

When he was just six, Marrogi’s family fled Saddam Hussein’s Iraq for Syria.

Marrogi at one point claimed three of his siblings had been killed in a bombing in Iraq.

It is unclear whether this was true, but Iraq was a difficult place for Assyrian Christians, and after a year in Syria, Marrogi’s mum, dad, brother Jesse and sister Meshilin arrived in Melbourne as refugees.

The three siblings were particularly close, but their parents’ split sent Marrogi into a downward spiral of anger and resentment.

Aged 12 and the runt of year 7A at Box Forest Secondary College, Marrogi was just like any other kid.

“I like maths because you always find a shortcut,” the future crime boss wrote in the school magazine.

“I liked maths in primary school, as well.”

A childhood friend of Marrogi’s told the Herald Sun he went from being a “teacher’s pet” to an “absolute menace” in just a few years.

“He was picked on because he was little, but near the end of year 8 he got big, quick, and started fighting back,” the former friend said.

Two years later, Marrogi had been lumped in year 9E.

“They were the dunces.”

“I never got what went pear-shaped with George, he was a friend for me, and then all of a sudden he was carrying a knife at school and rocking up at the canteen with $50 notes.”

Standing next to him in his year 9 class photo, head tilted like a punk, was Steve Slio, who, years later, would be jailed glassing a man in the face and slashing open his neck at a bar in for Fitzroy, leaving the victim with such horrific injuries he only just survived.

“Out of all that class, I figured Steve would end up in jail, probably George too, but if you’d told me what he (George) would end up doing, I would have told you to go get f---ed,” Marrogi’s former schoolmate said.

Accounts vary, but Marrogi either left for a fresh start or was kicked out of Box Forest Secondary that year.

Angry and resentful about his parents’ separation, he became abusive towards his mother, Madlin Enwiya.

He moved in with his dad and enrolled at Broadmeadows Secondary College, a rough school with a rough image.

“When you tell people that you go to Broadmeadows Secondary College, people get a certain idea of you,” a classmate told The Age deputy editor James Button when he visited the school.

“Because we have the name of the suburb, whatever happens around Broadmeadows is directed at us.

“There are a few stupid people here. But it’s the same in all suburbs.”

Marrogi, still a puppy-fat teenager, was not stupid but ultimately became one of the criminals who earned Broadmeadows its reputation.

One of the stupid people Marrogi met in his school years was Abdul “Abs” Elabed, a low-level crim who remained in Marrogi’s orbit for years.

The courts later heard Elabed got his hands on the stolen red Commodore Marrogi used in the murder of Ors.

Documents tendered in the Supreme Court when Marrogi was sentenced for Ors’s murder show one psychologist concluded his crime sprees were the result of him being “emotionally reactive”.

Another, Dr Stephen Mihailaides, thought Marrogi’s rage was “complicated” by his family and culture.

The Marrogi clan are Assyrian Christians, a group who are in equal measure devout and persecuted; precisely what effect religion had on Marrogi’s rage beyond “complicating” it is unclear.

Once, when Marrogi was in particularly deep strife, Ms Enwiya prayed for him: “In the name of Jesus Christ and Saint George … may George be shielded and protected from all who wish harm to him.

“May you grant him protection, peace, love, happiness, a heart faithfully devoted to you

so he can progress his life and attain a crown of glory in heaven”.

Ms Enwiya is the pillar of the Marrogi family, and George and Jesse are unfalteringly loyal to her.

She eked out a humble living for the family working as suburban driving instructor, but Marrogi had figured out an easier way to make a buck: stealing anything that wasn’t bolted down.

People close to Marrogi have described his approach to crime as “immature”.

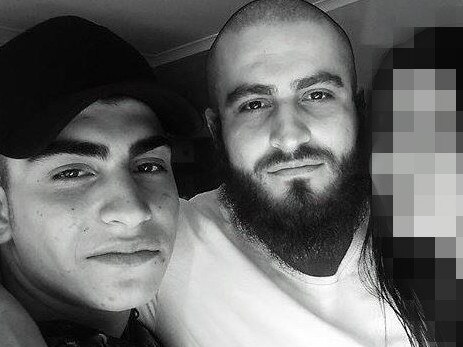

His gang, the Notorious Crime Family, briefly had an online store selling overpriced hoodies.

Marrogi’s younger brother Jesse brandished his “f--k the law” tattoos in a music video, standing amid a fleet of motorbikes, Lamborghinis and Rolls Royces.

For all the drugs, money and bloodshed, the Marrogi family’s version of being gangsters was the kind of thing a 12-year-old might imagine.

Immature attitudes towards violence are common among Middle Eastern organised crime groups.

Crisscrossed extended families often wage street warfare against each other, and

becoming ensconced in Hatfield-and-MacCoy type feuds sparked the kind of minor slights which would barely justify a punch-on.

The Parole Board rightly feared that Marrogi, once released, would step straight back into the street warfare that landed him in jail in the first place, but they could not keep him locked up forever. Within six months of being released from prison the last time, he unloaded a hail of bullets at Kadir Ors.

Prison, for the school dropout Marrogi, was a proverbial organised crime university, which he graduated from with honours.

In the months after his release, Marrogi became part of a new generation of MEOC figures causing chaos in the north.

“They were going to be crime wave number one,” a senior organised crime investigator said.

Their network and influence grew, spawning major issues with younger offenders acting under their instruction frequently involved in high-level crimes.

Increasing co-operation with outlaw motorcycle gangs compounded the issue for police.

And, as with so many of his contemporaries, Marrogi was learning from every brush with the law.