Andrew Rule: Graham ‘the Munster’ Kinniburgh’s Murwillumbah bank job was his masterpiece

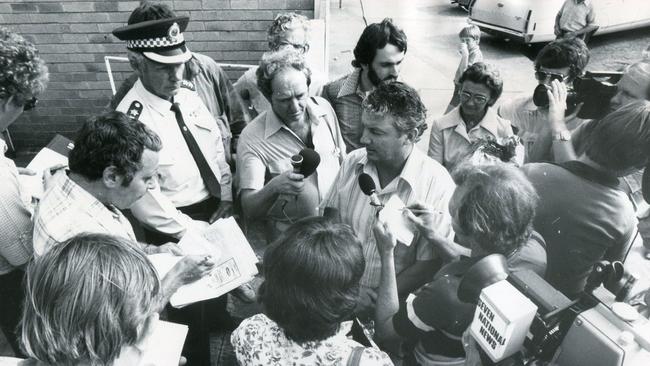

Graham Kinniburgh and his crew were long gone by the time a police inspector stuck his head through a hole in the safe and uttered a line that would appear on front pages across Australia: “They got the lot”.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

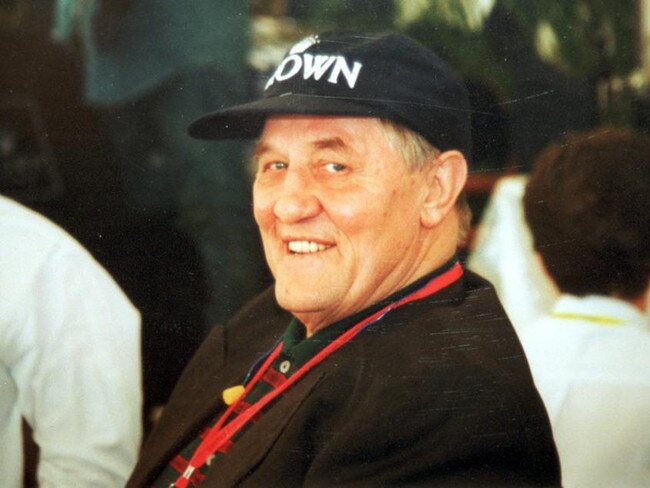

If the man they called “the Munster” was the safebreaker’s safebreaker, the Murwillumbah bank job was his masterpiece.

It is 45 years since Graham Kinniburgh led a crew through the back door of the country bank branch that happened to be crammed with a bumper stash of cash.

And it’s exactly 20 years this week since he was shot dead outside his family home in prim and prosperous Kew.

No one on the underworld war’s long casualty list was more widely mourned than Kinniburgh. He had friends from Little Italy in Carlton to the little Chicago on the waterfront, and was respected by his fellow painters and dockers, old-school police and everyone in the fight game.

He knew politicians and priests, punters and publicans, bookmakers and bankers and boxers but was especially fond of jockeys. They were handy in his line of work, which could require turning unexplained wealth into legitimate winnings.

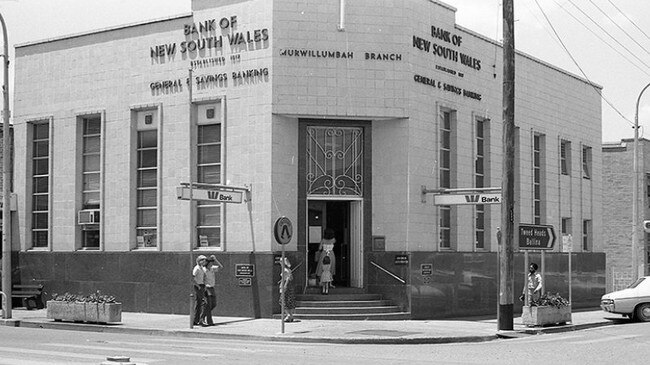

There were other safebreakers and other heists, but what happened at the Murwillumbah branch of the Bank of New South Wales bank in late November 1978 is the stuff of legend.

It’s the main reason that police and reporters started calling the Munster’s crew the Magnetic Drill Gang, although they pulled off at least a dozen other unsolved raids.

The magnetic drill was a piece of kit that allowed them to open the sort of “tanks” too highly-engineered and sophisticated for lesser thieves.

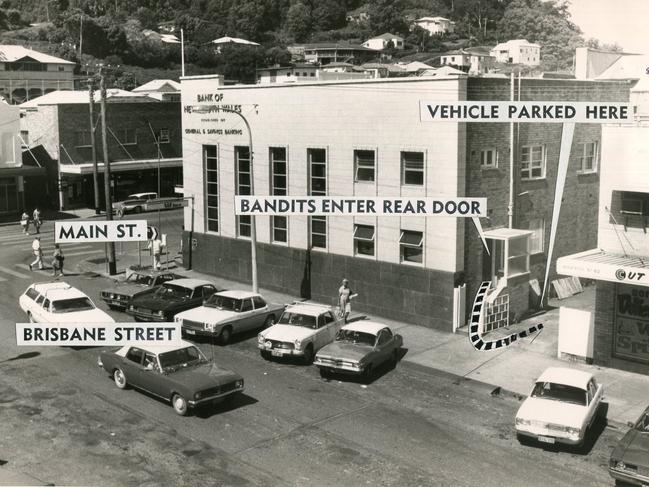

The safecrackers struck in the wee hours of a Thursday morning, November 23, 1978. They got through the back door of the old Bank of New South Wales branch in main street Murwillumbah, hub of the Tweed Valley farming district in the northern rivers area of NSW.

The day before, a Transecurity armoured truck had delivered an oversize load of Reserve Bank cash to cover fortnightly Government payrolls and pensions across the area.

Every second Thursday was payday. And with Christmas looming, there were holiday pay loadings for workers — and banks and businesses needed extra cash for the shopping rush.

The raiders didn’t have to kill an alarm system. There wasn’t one. They brought an ingenious mix of medical and mechanical gear to the task.

One was a fluoroscope, which uses X-rays to get moving images of the interior of an object. Doctors use fluoroscopes to scan the human body. Airports use them to scan luggage for weapons and contraband.

The gang had adapted a fluoroscope to detect the safe’s internal tumblers. Then they clamped an electro-magnetic diamond-tipped drill to the safe door and drilled a precisely placed hole above a crucial point in the lock mechanism.

They inserted a cystoscope, the thin flexible tube used by doctors to inspect patients’ bladders, in this case ingeniously modified to manipulate the lock tumblers.

It was as delicate, in its way, as surgery.

After emptying the safe, the thieves took the time to remove two combination lock dials before slamming the safe door shut so it couldn’t be opened except by massive destructive force.

Then they loaded the bags of cash into a getaway car and vanished, leaving hardly a trace, let alone forensic clues like fingerprints or footprints, discarded tools or material.

The bank was only 100 metres from the police station, which was manned overnight. But no one there heard or saw anything. Neither did late-night drinkers leaving the nearby Imperial pub opposite the bank. Nor did a night shift worker in the post office on the opposite corner.

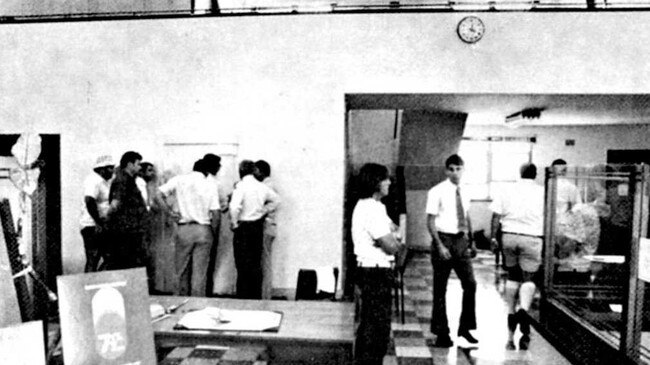

It wasn’t until 7.30am that a security guard noticed the bank’s back door was open and raised the alarm.

Local locksmiths and four safe experts flown from Brisbane worked on the safe door for five hours before giving up.

Finally, council workers smashed through the strongroom’s reinforced concrete wall, using jackhammers, chisels, oxy-acetylene blow torches and sledgehammers.

It was 4.30pm before the hole was big enough for a police inspector to put his head in. He looked around and uttered a line that would appear on front pages — and soon on souvenir T-shirts, tea towels and coffee mugs.

“They got the lot.”

The haul was $1.763m. In 2023 terms, that’s more than $10m, all in untraceable notes.

News of the audacious raid went around the world. Locals said it was the biggest thing to hit Murwillumbah since the killer flood of 1954.

It was Australia’s biggest bank robbery of all time and bigger than the official figure for the Great Bookie Robbery in Melbourne two years earlier (although subsequent inquiries suggested the bookies lost two or three times the $1.5m initially reported).

No-one had been threatened, let alone hurt during the raid.

Afterwards was a different matter. Knowing the violent ends some of the bookie robbers suffered, Kinniburgh was alert to the danger of predatory “toecutters” — jealous underworld rivals or, worse, corrupt police.

It might be that the gang had the police angle covered. Years later, it was revealed that a certain senior officer had been transferred from Sydney to the Tweed Valley just months before the robbery.

In those days, bent cops were often exiled to the country. The implication was that this cop was a rogue who’d tipped off the Victorian safe experts to a soft target full of hard cash. Bent Sydney cops loved “franchising” crimes for a cut of the action.

The cop in question resigned the following year and was subsequently named in the Stewart Royal Commission as a contact of notorious gangster and race-fixer George Freeman, who cultivated police, politicians and magistrates as well as racing people.

Meanwhile, more than 20 detectives from three states worked on the case but got nowhere. No one claimed the $250,000 reward and the Murwillumbah robbery became part of folklore.

Of course, there was never any smoking-gun proof that Graham Kinniburgh was behind the crime. But the fact was that he and his tight knit crew had perfected the magnetic drill technique which was used 14 times in less than two years.

It was known in underworld and police circles that Kinniburgh’s team had obtained high-grade safes and practised opening them in an empty warehouse. The Munster had the sort of technical and tactical brain that might have made him a captain of industry or a brilliant military officer had circumstances been different.

He was not just analytical and calm but decisive and occasionally dangerous. Once, in a crowded nightclub, when his erratic and violent friend Brian Kane was threatening to cut off an enemy’s head, Kinniburgh averted bloodshed and arrests by knocking the gun out of his hand.

He was a career crook and yet did not have a long criminal record beyond the usual youthful excesses. He was rarely charged, let alone convicted, of anything major.

In the weeks after the Murwillumbah job, police and the media had nothing new to add to the story but the drums were beating in the underworld.

Kinniburgh’s flamboyant and volatile contemporary (and sometime accomplice) Steve Sellers, was a cop-baiter and hater, and so Kinniburgh had left him out of the Murwillumbah caper.

Sellers was demanding a cut of the proceeds but he was trying to intimidate the wrong man. He got what was coming to him, and it wasn’t money.

On February 2, 1979, nine weeks after Murwullimbah, Sellers took a telephone call in the lobby of the Domain Motel in South Yarra. That’s when someone with a shotgun shot him three times in the back at close range.

Sellers didn’t die immediately. He said nothing to detectives who came to his hospital bedside. But it’s widely accepted that Kinniburgh pulled the trigger, wounding a man much disliked by police who posed a danger to several people. It was a shooting that might not have been probed as hard as some.

The best proof that Kinniburgh’s crew did the Murwillumbah raid is that it matched exactly the unique methods of other safecracking jobs credited to the same crew, mostly in Melbourne. Interpol told Australian police that no other known safecrackers in the world used the same methods.

Kinniburgh’s judgement was sharp enough that he gave up safebreaking before new security technology caught up. He invested his money and kept his hand in with less risky capers on and off the racecourse.

But by the late 1990s, of course, he was known for his association with big players in the underworld war — mostly for witnessing Jason Moran kill their mutual associate Alphonse Gangitano in his Templestowe home in early 1998.

Seasoned homicide investigator Charlie Bezzina and another detective went to talk to the young Moran at his house in Moonee Ponds. Kinniburgh happened to turn up with Lewis Moran while the detectives were there.

Bezzina found Kinniburgh a more likeable rogue than most he dealt with, including the Morans. But he didn’t underestimate him.

He and the other detective guessed they were the only ones in the room who were unarmed that day. They were definitely the only two who are still alive, as both the Morans and Kinniburgh were executed over the next few years.

Bezzina’s firm opinion about the Gangitano murder reflects the coroner’s finding that Kinniburgh was present but played no part. He had arrived under his own steam while Moran had arrived with one Russell Smith.

Kinniburgh’s blood and tissue were found on a security door, almost certainly left there in his haste to get out of the house and set up an alibi by rushing to a nearby service station to buy cigarettes.

That way he could claim Gangitano “was alive and well when I went to get the smokes.”

The coroner didn’t believe that bit of Kinniburgh’s story but it did the trick. He was never going to be charged over Gangitano.

A measure of the man was that when he saw Gangitano’s wife drive past on her way home, he rushed back from the service station to the house to help shield her in her time of distress. He might also have removed the tape from the Gangitano security camera.

He had a heart as well as a brain but it didn’t save him from heartless, brainless killers.

Graham Allen Kinniburgh was shot in his own driveway in Belmont Ave, near Kew cemetery, on the same date that American forces dragged fugitive Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein from a hole in the ground on December 13, 2003.

The doting grandfather and retired safecracker was fetching home an armful of groceries late at night when the hitmen opened fire.

The Munster managed to pull out a pistol and get off one shot but it was too late. He was 61.