Slain Melbourne underworld peacemaker Graham Kinniburgh was an ‘honest crook’

SPECIAL REPORT: NOT many wiseguys are wise, but Graham Kinniburgh came close. The master safecracker was a natural diplomat and a cool head in Melbourne’s lethal underworld game. Andrew Rule and Mark Buttler report.

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Letters revealed: Did Carl Williams order more murders?

- Benji, Carl and the Esky in the boot

- Munster died in shootout with killers

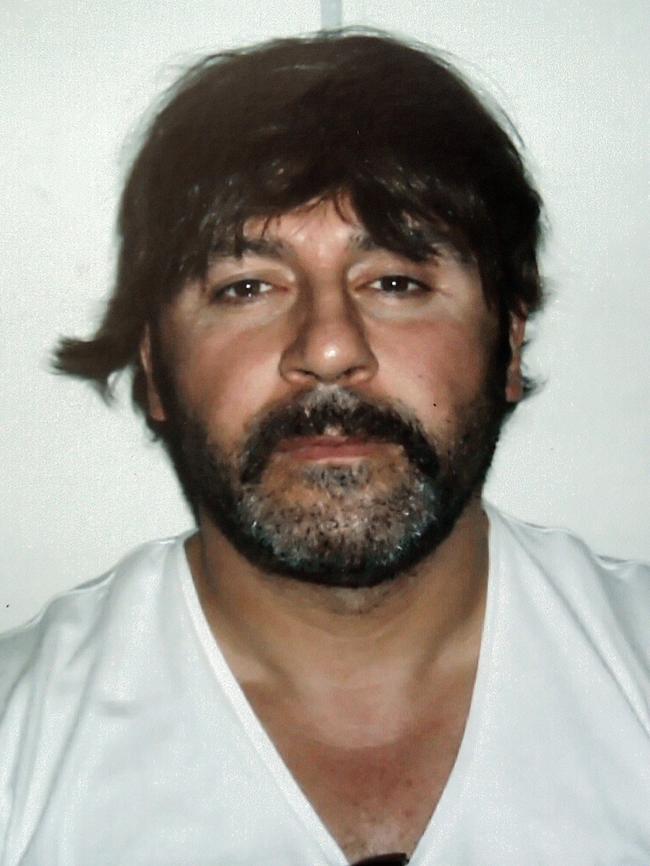

NOT many wiseguys are wise but Graham Kinniburgh came close.

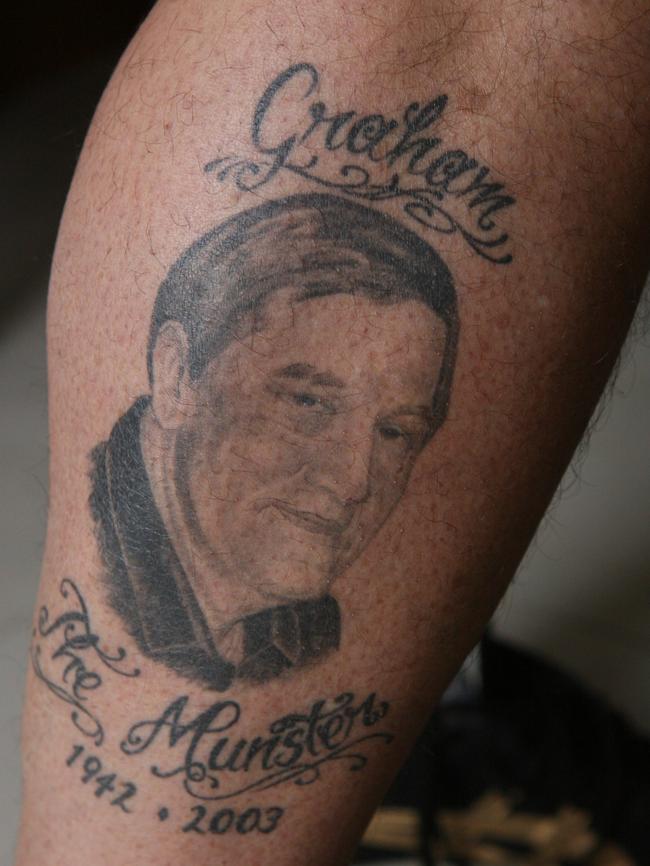

Right up until the night paid killers shot him down in his own driveway, the man they called “the Munster” had a name as an underworld deal broker and peacemaker.

In several decades of staying alive and out of jail, Kinniburgh had saved people in the underworld from themselves and from others.

But, in the end, the one-time master safecracker couldn’t save himself from being murdered to satisfy the bloodlust of a delusional drug dealer.

Compared with the mad, bad people in his world, Kinniburgh was more Kissinger than Dillinger, a natural diplomat and a cool head in a lethal game.

He was not only what old-time police a “good crook” but an “honest crook” as well.

This showed itself in small ways and large, from massive (and unsolved) safecracking heists in the late 1970s and early 1980s through to flogging “hot” goods in pubs.

Kinniburgh had seen underworld wars before the one featuring Carl Williams, “Benji” Veniamin, the Moran family and the rest.

Such as when armed robbers Raymond Patrick Bennett (alias Ray Chuck) and his mates Laurie Prendergast and Vinnie Mikkelsen were acquitted of abducting and killing painter and docker Les Kane in 1978, and Kane’s brother Brian became obsessed with revenge.

Kane saw Mikkelsen’s barrister at a nightclub and told him he was “going to cut your client’s head off and leave it on your front door step”.

This suggested he might do something silly, so when Kane pulled a gun on the same lawyer later, his mate Kinniburgh averted trouble by knocking the gun out of his hand.

He had fast hands and a quick mind.

The death of Big Al

After Kane was shot dead in a Brunswick pub in 1982, Kinniburgh widened his social circle to include Lygon St identity Alphonse Gangitano.

In fact, he was at Gangitano’s Templestowe house with Jason Moran on the hot night “Big Al” was shot dead in his underpants in January 1998.

Kinniburgh, knowing his presence (with the alleged shooter, Moran) could be misconstrued by the law or Gangitano’s few remaining friends, rushed from the house, went to a convenient convenience store — conveniently equipped with closed circuit cameras — then returned in time to comfort Gangitano’s wife, who had arrived home just after the shooting.

GANGITANO, MORAN AND THE SMOKING GUN

All of which meant he had a plausible alibi to avoid being charged over a murder widely blamed on Jason Moran.

Unfortunately for investigators, the security camera in Gangitano’s house was turned off.

Police believe Kinniburgh checked it after the shooting, just in case.

In truth, Kinniburgh liked to avoid gunplay because it attracted unwelcome attention that interfered with cash flow.

The evidence from Gangitano’s house is that he was shocked when his host was shot in front of him.

The brain behind a legendary gang

Strangers who met the polite grandfather at the races in the 1990s found his reputation hard to credit.

This was that he was the brain behind the fabled “magnetic drill gang”, which had got away with several million dollars in the late 1970s and early 1980s, most of it from two massive bank strongroom “jobs” — one in the northern NSW town of Murwillumbah in 1978, the other a Sydney bank in 1983.

The gang scored more than $7 million in an era when suburban houses sold for less than $50,000.

An old-school detective ran into Kinniburgh at a Caulfield Cup meeting and introduced him to the woman he was with.

She was charmed by his conversation — especially when he explained he couldn’t stay after the last race because it was his birthday and his wife had organised something at home.

“When he left,” recalls the since-retired policeman, “she said ‘What a lovely, lovely man’.”

“I said, ‘He is, isn’t he? He’s also the best safebreaker in Australia’. She just wouldn’t believe me.”

MAGNETIC DRILL GANG: HOW THEY GOT AWAY WITH RECORD HEIST

The same detective once saw Kinniburgh at Moonee Valley races just after a big heist that had lawmen and law-breakers humming.

“He said, ‘You know, I was the best’.”

“I said, ‘Graham, they tell me you’re still the best’. He said ‘Turn it up’ and walked off to the mounting yard.”

It’s no coincidence both meetings were at the track.

After the races at Flemington or Moonee Valley, if Kinniburgh had backed certain winners — or avoided backing certain losers — he would meet a favourite jockey at Jimmy Wong’s legendary Chinese restaurant in Footscray.

He always ordered the tasty dim sims made on the premises.

“Good boy,” he’d growl affectionately, discreetly palming the jock a wad of cash, possibly in a brown paper bag.

As one regular payee recalls with some warmth, “the Munster” wasn’t one to break promises or duck payments.

He paid promptly and well for the right information, which is why he had so much of it.

Even senior police who wouldn’t normally bet on the sun rising were happy to get a Munster tip. He was the nearest thing Melbourne had to Sydney’s “colourful racing identity” George Freeman, who also had a wide circle of acquaintances fascinated by uncannily accurate tips.

Kinniburgh moved easily between Jimmy Wong’s and the Flower Drum in the city — the main difference being the price of fried rice, he once joked.

“The Drum” was a little public for some meetings. When he wanted to be more discreet, he would meet certain jockeys at Choi’s restaurant in Hawthorn, conveniently close to where they both lived.

An occupation is a hard thing to pin down

When the boxer Barry Michael was heading towards his world title belt in the 1980s, he recalls, Kinniburgh was “in his corner” financially, helping set up a training gym in Flinders Lane in a building Michael thinks he owned.

“He was an absolute gentleman. He backed me against all of them (opponents) and won fortunes on me. But I never knew he was a safe cracker.”

Kinniburgh “worked” odd hours, if not playing games of chance then talking to people who could tilt the odds in his favour or others who might fancy buying quality goods at a heavy cash discount.

He’d be in a pub here, a motel there, a restaurant somewhere else. Nothing was too big or too small.

He was good at his trade — it’s just that no one knew exactly what it was. Even he was a little unsure.

Asked his occupation when police interviewed him after the Gangitano murder, he looked blank and stumbled before remembering that he was “a rigger”.

Presumably he meant a rigger that works on tall buildings and bridges, rather than rigging horse races or other ways of redistributing wealth.

The Clare Castle Hotel in Port Melbourne was one of his regular haunts.

He would turn up on the same weekday morning a few times a month and nurse a small drink while a large bodyguard stood with his back to the bar, studying who came in.

Sometimes Kinniburgh would sit down to chat with a contact.

During one such meeting, a flustered waitress approached the publican and whispered that a gun had appeared on the floor underneath Kinniburgh’s table.

“Don’t worry,” said the publican. “Just go over and kick it back out of sight and act natural.” She did, and “the Munster” calmly retrieved the pistol, slipped it back in his pocket and kept talking.

Sometimes he would borrow a side room at the pub so clients could try on high-quality clothes or jewellery he happened to have in the car. But he mostly left the retail side to a trusted associate, the late Byron Pantazis.

The Kinniburgh travelling emporium offered a wide range. Sometimes it would appear in an upstairs motel room in inner suburbs.

While Pantazis showed off the latest clothes and jewellery, Kinniburgh would sit in his car outside, ready to phone a warning if anyone unexpected turned up.

TONY MOKBEL: PIZZA COOK TO MR BIG

One occasional customer still prizes the imported tweed jackets and silk ties he got from the car boot boutique. “And they could get you crayfish, oysters, anything you wanted,” he recalls.

Kinniburgh’s sidekick Pantazis was a man of many parts — mostly stolen.

He and his wife would be accused of obtaining the yacht used to smuggle drug baron Tony Mokbel from Australia to Greece, and of driving him across the Nullarbor disguised as a deaf mute.

But that was later, after Kinniburgh was killed for no reason other than the fact Carl Williams’s hirelings could not get an easy shot at Lewis Moran.

“Strength is not measured down the barrel of a gun.”

It happened on December 13, 2003, the same Saturday that American special forces finally dragged Saddam Hussein out of a hole in Iraq.

It says a lot about Melbourne’s fascination with the underworld war that the Kinniburgh hit was almost as big a story in these parts as that of the tyrant’s capture.

Kinniburgh had always been a nocturnal animal. Even when the whispers reached him that he could be next on the Williams hit list, he wasn’t scared of the dark. Perhaps that’s what got him killed.

His wife was in bed reading when she heard “loud bangs” just after the midnight radio news as Friday night turned into Saturday morning.

Sybil Kinniburgh would tell a jury much later she heard “maybe three, maybe more” bangs that she did not realise were gunshots.

“I couldn’t work out what the noises were, so I got out of bed and walked to the front of the house,” she said later. But she couldn’t see anything unusual through the trees at the front of the family’s brick house in one of Kew’s better streets, so she went back to bed.

Then she heard police sirens, a knock at the door and the bad news.

Her husband of 36 years had been ambushed as he got out of his car carrying a bag of groceries. He had managed to fire one shot back but it didn’t help.

She said she did not know her husband had carried a gun or even that he was in any danger because he would not have told her.

A big crowd of mourners turned up at Sacred Heart Catholic Church a few blocks from the Kinniburgh’s solid two-storey red brick house.

The venue was a departure from other gangland funerals at the Mafia church of choice, St Mary’s Star of the Sea near Queen Victoria market in West Melbourne.

They played a song called The Last Farewell as “the Munster” took his last ride.

Former Pentridge prison chaplain Father Peter Norden stuck to the good parts of a life of crime in his eulogy, drawing the moral that “Strength is not measured down the barrel of a gun.”