Charlie Bezzina, Jason Moran and the 'smoking gun' in the Alphonse Gangitano underworld murder

CHARLIE Bezzina knew who killed Alphonse Gangitano in a bloody hit, but proving it was an entirely different thing.

The Investigator

Don't miss out on the headlines from The Investigator. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS investigators close in on the prime suspect in the slaying of gangland heavy Graham Kinniburgh, we revisit another of The Munster's encounters in the underworld.

This report was first published in True Crime Scene in March 2012.

THE paper bag that held the gun that killed Alphonse Gangitano flew off the West Gate Bridge, over the railing and into the darkness in the early hours of January 17, 1998.

It was literally the smoking gun that would have put the killer, Jason Moran, behind bars - possibly stopping Melbourne’s gangland war before it began.

Cops have prime suspect in The Munster's hit

The next year Moran shot his drug rival Carl Williams in the stomach, an act that sparked more than 20 tit-for-tat underworld slayings.

“Had they found the pistol, I was in a position to go straight out and charge Jason with murder,” former Detective Sgt Charlie Bezzina says.

Gangitano’s execution is one of the few cases in an exemplary 17-year career as a homicide investigator that Bezzina will never be able to officially describe as "solved”.

There’s no doubt in his mind that Jason Moran was the killer.

But being able to charge him with murder - and prove it - was another thing entirely.

Gangster traded in fear

THEY’D probably queued to get in, but many of Billboard’s patrons couldn’t get out the door fast enough when Alphonse John Gangitano made his presence known on September 7, 1993.

Police arrived to find terrified patrons fleeing and “there wasn’t a straight pool cue in the place”, according to the first officer to enter the Russell St bar after reports of an armed man inside.

Gangitano was searched but they didn’t locate the gun.

What they did find were several staff members who’d been assaulted - none of whom wished to make a complaint against him. It was a familiar story.

Fear was a weapon Gangitano was able to employ as effectively as any other as his reputation for violence spread beyond Carlton’s Lygon St in the late 1980s.

Former undercover policeman Lachlan McCulloch wrote in his book that Gangitano was able to carjack luxury vehicles he fancied, armed with nothing more than his name and a request for the driver to hand over the keys.

He became known for attacking off-duty police officers and extorting cash from bar and nightclub owners, threatening to bash patrons if management refused to pay.

His father was a successful Lygon St businessman and sent him to private schools, but even as a teenager the Gangitano name meant trouble.

Police first arrested him as a 19-year-old for offensive behaviour, and within a few years he was carrying a gun.

Gangitano made his money from illegal gambling, standing over local businesses and bars, and promoting fights.

He had part of an illegal card game run by Carlton identity Mick Gatto, in the days before the casino.

But he kept starting fights with the customers.

“”It became a bloodbath,” Gatto says in his autobiography. “People stopped going because they were afraid, and we lost a lost of clients.”

They fell out several times but Gatto – who would later start his own “mediation” business - was always able to sort things out, even after Gangitano tried to fight him in a Carlton restaurant in 1996.

Mark “Chopper” Read had also fallen out with Gangitano in the past, but had little interest in mediation.

The notorious standover man had once been ambushed by Gangitano’s crew, and wasted no time trying to track him down after being released from prison in 1991.

Gangitano was so scared that he packed up and fled to Italy with his young family, returning only when Read was back behind bars.

The crook turned crime author dubbed him the Plastic Gangster.

"Every time Al needs some advice he puts on 'The Godfather' movie to see how Marlon Brando did it," Read once wrote of Gangitano.

Charming, yet brutal

But he was no Don Corleone. He was said to have been a fan of the once-banned film A Clockwork Orange; like its anti-hero Alex, Gangitano could be charming and articulate, professed a love for the arts, and had lashings of “the old ultraviolent”.

His acquaintances included a bail justice and a professor of music. He loved reading about historical figures: Napoleon, Hitler, Al Capone.

He was a big punter but not a successful one, and it was rumoured he’d lost a packet when Barry Michael took the IBF super featherweight title from Lester Ellis in 1985.

Two years later Gangitano saw Michael having a quiet drink at Lazar’s in King St. Gangitano bit him and his crew broke his nose. The beating effectively ended Michael’s career.

"I was lucky to get out of the place in one piece,'' Michael later told the Herald Sun.

Well-liked petty crook Greg Workman wasn’t so fortunate.

On February 7, 1995, a drunken Gangitano shot him eight times outside a party in East St Kilda.

Two sisters saw him standing over the body and made statements to police.

They were placed in witness protection as investigators tried to build their case against Gangitano.

He was interviewed three times over the shooting, but it was not until two months later that he was charged with murder.

But by then it was too late.

Murder charge dropped

Feeling isolated and abandoned in witness protection, the two star witnesses contacted a man they knew could help them: Jason Moran.

You don’t still think I killed Alphonse do you Mr Bezzina?

He arranged for them to be collected from their remote country location and brought to Melbourne, where they secretly recanted their statements. They told prosecutors they would no longer cooperate.

Police believe Gangitano then paid for flights to England for the pair, covering all their expenses.

It was a small price to pay for his freedom.

The charge of murder was withdrawn shortly afterwards. But the close call did little to deter his public violence.

In December 1995, just months after Gangitano’s murder charge was dropped, he again flung himself into the spotlight with an ugly incident in King St’s notorious bar strip.

Without warning Gangitano and Moran had viciously attacked at least ten patrons at the Sports Bar, using pool cues until they broke and kicking those who fell to the ground hurt.

One woman’s jaw was broken and South African visitor Campbell Lawler suffered long-term eye damage.

"He had dark eyes, I will recognise him anywhere I go,'' Lawler later said of Gangitano.

His blood was later found smeared inside Moran’s coat: a damning smudge that, coupled with the tourist’s evidence about the brutal assault, would one day convict Moran of a count of affray.

Moran was later recorded on a police bug saying he had to shower “to wash the blood off" and admitting he’d sparked the fracas.

But even Moran was in agreement with the witnesses from the Sports Bar that night: it was Gangitano who escalated the violence.

“He’s f..ng lu-lu,” Moran once told a lawyer. “If you smash five pool cues and an iron bar over someone's head, you're f---ing lulu''.

Both were bailed over the incident and due to face the Melbourne Magistrates’ Court on January 16, 1998.

Gangster fiddled as court threat loomed

GANGITANO spent the early hours of that morning listening to a song from an opera that his friend had written about him.

He had been so eager to hear the composer’s ode that he’d called the composer four times between 9pm and midnight.

Gangitano had lost his licence but had a driver, Santo, whom he sent to the composer’s studio to collect the recording and its creator.

His lawyer sat with him at the kitchen table as they listened over and over, with Gangitano interpreting the Italian lyrics for him so he could identify anything “incriminating”.

“Al also spoke about Gudinksi wanting to make a film about Al and his associates,” the composer later told police. “Al said that if they were going to make a film about him that I had to make sure Andy Garcia play his part. Virginia was present at the time and both Virginia and I tried to talk him into doing it.”

Gangitano had met his partner Virginia when they were both teenagers. They lived together for 15 years and had two daughters. The dutiful mobster’s wife, she knew he wasn’t a “property consultant” but didn’t ask what he did when he left for in his chauffeured car each day.

Her husband had been in jail and often spoke of his hatred for police. He’d installed a surveillance system because he was worried they’d try to sneak in and bug the house.

Still she considered Alphonse a devoted father and husband, who was even trying to rearrange their mortgage so she could manage the repayments if he went to jail.

And that was a very real possibility as the hearing for the Sports Bar brawl loomed.

The falling out with Jason Moran

Gangitano fronted Melbourne Magistrates’ Court after 10am, and a police officer noted a distance between him and his co-accused Jason Moran.

Gangitano’s lawyer George Defteros said his client planned to "strenuously defend" his 20-odd charges of affray and assault.

But it was rumoured that Gangitano, who was by then aged 40 and facing a raft of other assault charges, was going to plead guilty.

Such a move would leave Moran - who was tied to the Sports Bar bashings through Lawler’s blood - in an uncomfortable legal position.

Gangitano left court around 11am, met with his legal team then had lunch.

His driver picked him up at 3.30pm and took him home to Glen Orchard Close, Templestowe.

Gangitano had a 9pm curfew but throughout the evening he spoke on the phone to several associates, including Perth identity John Kizon and a friend at Fulham prison.

His wife rang at 9.36pm to let him know when she would be home from visiting her sister.

His mistress rang later and they chatted about his day in court, which Gangitano thought “went well”. He was relaxed and “at ease”.

“Al told me that there was someone at the door and that he would have to call me back,” the mistress told police.

It was the last time they spoke.

Wife's bloody discovery

Gangitano’s wife pulled into the driveway at 11.45pm and the children raced ahead to the door, ringing the bell.

She was juggling wet towels, beach bags and a carry bag of drinks, but immediately noticed a dent in the security screen that had not been there when she left.

As she put her key in the door it opened.

Police raid, was Virginia’s first thought – it had happened before. She called out to her husband but heard no reply.

As she turned towards the laundry she saw him.

After telling the children to stay away she called 000. “I couldn’t speak as freely as I would like because the children were nearby and I didn’t want them to hear. I was asking them to hurry. I was told to check his pulse, which I did. He wasn’t cold.”

She was still talking to the operator when the sensor lights came on. It was Gangitano’s close friend Graham Kinniburgh.

The Black Prince's humiliating end

“THE Munster” was a life-long crook, but otherwise the pair had little in common.

Gangitano thrived on violence and intimidation. Kinniburgh, who was 16 years his senior, was known as a peacebroker.

And where Gangitano craved notoriety The Munster had spent years flying under the radar, despite being considered one of the country’s most successful safe-breakers.

Kinniburgh was someone Virginia knew she could trust.

He helped her roll her husband’s body over.

“I could see that his eyes were open and I knew that he was dead,” she said.

Gangitano liked to be considered well-dressed and owned many expensive suits.

But when Bezzina and the other homicide detectives arrived, they found the Black Prince of Lygon st on a laundry floor in his underpants and singlet.

For Bezzina, it was a vital clue about the identity of Gangitano’s killer.

“He wouldn’t open the door in the underwear, so we know it’s someone he’s comfortable with. He’s a vain sort of bloke,” Bezzina says.

The crime scene itself held other evidence.

The dent in the screen door that Virginia had noted when she arrived home was at elbow height and there was human tissue visible, which was taken for DNA testing.

A bullet was located in the laundry wall, and Gangitano had been shot once in the back and twice in the head.

A reconstruction of the likely trajectories of the four shots indicated to Bezzina that one shot had missed, and Gangitano was running for the laundry when he was shot in the back.

He was then finished off with two to the head.

There was a clothes horse blocking the laundry external door, which suggested that rather than trying to flee the house Gangitano may have been seeking a weapon hidden there.

None was found, but his killer may have taken it, Bezzina says.

Tapes were missing from Gangitano’s security monitor, which was housed in a linen cupboard upstairs.

It would later emerge that Gangitano only occasionally recorded off the security cameras.

But Bezzina says a blood droplet on the upstairs banister outside the cupboard meant somebody - most likely the person who had injured themselves on the screen door - had known they might have been filmed, and where to find the potentially incriminating tapes.

Witnesses were equally important to the investigating team.

The Munster is quizzed

They quickly ruled out Virginia as a suspect and turned their attention to Graham Kinniburgh.

He told the detectives he had arrived to visit his friend around 10.40pm, but was told Gangitano was expecting someone and to return later.

Kinniburgh said he headed out at 11pm to a Quix service station in Blackburn Rd to by cigarettes and returned to find Virginia with Gangitano’s body.

But the service station was only 2km away and he could offer no explanation as to why it took him 45 minutes.

He was sporting a fresh graze near his elbow.

Old-style criminals like Kinniburgh rarely cooperate with police, so his willingness to hang around and make a statement immediately aroused Bezzina’s suspicions.

But Kinniburgh was friendly with Gangitano, and while his record included some serious offences murder wasn’t one of them.

Gangitano had more enemies than friends, so Bezzina decided to start by tracking down his associates and find out what had been going on in the slain thug’s life.

Jason Moran was the obvious starting point – he’d been at court with him that very day.

Bezzina sent three detectives off to find him.

Others were tasked with checking out Kinniburgh’s story by obtaining the CCTV footage from the service station.

He’d been there all right. But the time stamp read 11.45pm, and he was only there for as long as it took to buy a packet of cigarettes.

What the witness saw

IT was 11.25pm and the young man argued with his girlfriend as they drove down the incline of Glen Orchard Close and parked.

The debate continued as they sat in the car. Welcoming the distraction, the male watched a stocky man walk quickly past and down a driveway. The security lights came on as he did.

Shortly afterwards he saw the same man leave the property and walk away with another man. The two men went their own ways.

The male witness later described the first man he saw to Bezzina’s detectives. He had either close-cropped hair or was bald; he wore a white top, and had tattoos on his arms. Of that he was certain.

He sat down with police and created a identikit of the man.

“You could hold the photo fit in one hand and a photo of Jason in the other and not tell them apart,” Bezzina says.

It would have been the perfect description if not for one rather important detail: Jason Moran did not have tattoos.

Moran had been difficult to locate in the hours after the murder. But his lawyer, Andrew Fraser, contacted Bezzina and agreed to bring his client in to speak to detectives on January 18, more than a day after Gangitano’s death.

He was “obviously nervous and a bit cocky”, Bezzina says, but answered “no comment” to every question. His wife Trisha gave him an alibi.

But once they were armed with the witness’s identikit image, Bezzina was sure they were on the right track, in spite of the problem with the tattoos.

He asked Moran to take part in a line up with their eyewitness. The request was declined, but that didn’t prevent Bezzina’s team from showing him a video line up including footage of Moran.

The witness picked him out as the man he’d seen entering Gangitano’s property that night.

He would later give evidence at an inquest years later, with Moran present in court. He agreed the tattoos may have been shadows, and was a solid witness. The coroner, Iain West, would later say he was satisfied Moran was the person the witness saw that night.

But a coroner’s inquest and a Supreme Court murder trial are very different proceedings, each with its own rules of evidence.

I think Jason Moran is the kind of person who could kill or harm me to keep me quiet

Face to face with Moran

Bezzina says his practice was to always think like a defence barrister - and if the witness was wrong about the tattoos, a lawyer could argue he had also identified the wrong person.

The line up had been a useful exercise, but hardly sealed their case against Moran.

In the weeks that followed Moran the murder was at pains to let Bezzina know he had the wrong man.

They approached Moran’s neighbours one afternoon to find out if they’d seen him on the night of the murder, but got little help from the terrified residents.

But thinking they were looking for him, Moran called out to Bezzina and his colleague Gavan Ryan and invited them in to chat.

He was adamant he had nothing to do with Gangitano’s death.

“He was a lot more confident that we had nothing hence his more animated and vocal denials,” Bezzina says. The seasoned detective was equally vocal about his determination to prove that he did.

As the two long-serving detectives stood talking to their chief suspect, Moran’s father Lewis and their other “person of interest” in the Gangitano case, Graham Kinniburgh, arrived at the house.

Lewis Moran was also a career criminal and long-time associate of Kinniburgh. They strictly adhered to the old criminal code of silence when it came to dealing with police.

The detectives exchanged a long, silent glare with the arrivals, then left.

Kinniburgh also refused to take part in an identification parade, and when called back in to answer more questions resorted to “no comment” responses.

He did consent to a blood sample being taken, and had no problem with them searching his house. Police found nothing.

Bezzina kept the identikit image and their eyewitness under wraps as the investigation progressed. It was the best evidence they had, and they didn’t want to share it with their key suspects just yet.

But without a weapon and little prospect of Kinniburgh telling them what really happened, the investigation stalled.

Three months later, they got their biggest break yet.

Toe to toe with murder suspect

And Moran remained cocky.

Things almost came to a head in a chance meeting at Melbourne Magistrates’ Court one day.

Moran, who was with his lawyer, approached Bezzina in the foyer.

“You don’t still think I killed Alphonse do you Mr Bezzina?” Moran teased.

“Not only do I think you did it, but I’m going to prove it,” Bezzina told him.

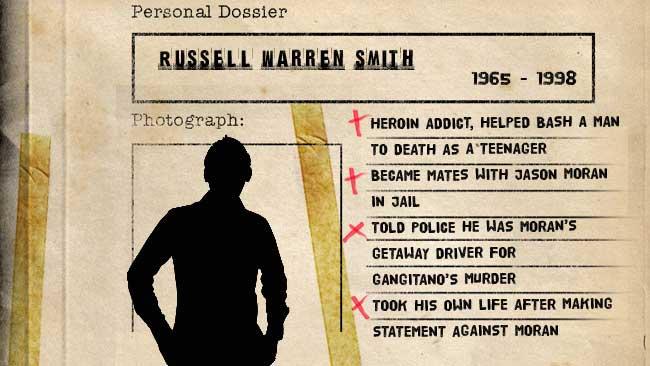

Read Russell Warren Smith's statement to police in full

The getaway driver

RUSSELL Warren Smith was just 18 when he helped kick a stranger to death in a St Kilda car park in 1983.

He’d only left home a month before, having led an ordinary suburban life with a loving and supportive family.

He had been a good student and worked steadily after leaving school, but was easily led and it didn’t take long for St Kilda’s streets to claim him.

He fell in with the likes of prostitute Jodie Jones, whose sad childhood could not have been more different to his own.

Jones had lived a series of tragic episodes: abandoned aged 2, pack-raped at 11, homeless at 14 - and a killer at 19. She later died of a heroin overdose – but remains a suspect in one of Victoria’s most baffling cold cases, the disappearance of Sarah McDiarmid from Kananook railway station in 1990.

Smith, Jones and two other teens pleaded guilty to manslaughter over the St Kilda death, and were jailed for at least ten years.

While serving his sentence Smith met a young inmate named Jason Moran in the yard one day. They got on well, but Moran appeared to be under the misapprehension that his name carried more clout than it did, Smith would later recall.

“He was always big-noting himself and I remember his big line he used to use was,” Do you know who the f… I am?”,” Smith said.

“I don’t know why he said this as Jason was only a young kid and nobody in jail had heard of him.”

Smith and Moran reconnected on the outside years later. If anything prison had enhanced Moran’s capacity for violence.

Smith recalled an incident where a motorist cut Moran off as they drove on Punt Rd. When they stopped at a red light Moran used a wheel brace to smash in the driver’s window and dragged the terrified man from his car.

“Jason beat this man quite severely,” Smith would later tell police. “After assaulting this man Jason got back in the car and was laughing.”

Smith was introduced to members of the Lygon St crew, including Alphonse Gangitano.

Around 1996, Smith progressed from cannabis to heroin and as soon as members of the Lygon St crew found out they dropped him “like a hot potato”.

But he stopped using and in January 1998 ran into Moran for the first time in years, while watching a lunchtime strip show at a hotel in Campbellfield. They had a drink, smoked some marijuana and chatted about old times.

' Lets go for a drive'

At 9.45pm that night Moran suggested they go for a drive. He threw Smith his keys and asked him to take the wheel. The car had “no smoking” stickers and the general look of a hire car.

Moran directed Smith to Templestowe. They stopped outside a house and Moran told him to wait.

“He said,” You can’t come in. Just wait here I’ll be back in five or ten minutes”,” Smith told police.

Moran walked up the street and Smith said he didn’t see which house he entered. About 15 minutes later he spied Moran walking back.

“He jumped into the passenger seat. Jason didn’t seem any different to when he left,” Smith said.

Moran directed him back towards the city, “still chatting away”. They passed a McDonalds on City Rd and bought hamburgers, then headed over the West Gate.

“When we got to the very top of the bridge Jason put down his window. He threw his McDonalds bag out of the window over the railing of the bridge. We were driving at that time in the far left lane heading towards Williamstown. The McDonald’s bag would have ended up in the water below or near there anyway.”

The next morning the news came over the radio that there had been a murder in Templestowe.

“As soon as I heard Templestowe I started to get nervous,” Smith said.

And when Gangitano’s identity became known Smith said he realised Moran was involved.

“I started to think about what had happened. It was then that I realised that when Jason threw his McDonalds bag out of the car that it had gone a fair distance. It seemed unusual as normally the wind would have grabbed it but it did not appear that way.”

Moran's warning to Smith

Two days later Moran showed up unexpectedly at Smith’s flat at 7am.

“He said, “Alphonse has been put off”, “Smith said.

“Well listen don’t talk to any of the crew … and don’t tell anyone you were driving me the other night,” Moran allegedly said.

Smith said Moran told him not to go to Gangitano’s funeral as there would be police everywhere.

The visit left Smith in little doubt that Moran was the killer.

“I was scared for my own safety as I thought that Jason may harm me or do something to keep me quiet,” Smith told police.

“I think Jason Moran is the kind of person who could kill or harm me to keep me quiet.”

A new lead for detectives

SMITH said nothing about the murder until some four months later, when he was arrested for stealing cars. A few days languishing in the Preston watch house gave him time to stew on the dangerous knowledge he held about the Gangitano murder - and his fear that he was simply a loose end waiting to be snipped by Moran.

He told the local detectives he had information on the case and soon found himself talking to members of Bezzina’s team.

“Not only am I sick of always looking over my shoulder for Jason Moran, but I just want to change my life around,” Smith later said. “I want to make a fresh start and I am sick of my whole life.

“I look on this as the first and most important step.”

Smith did not strike a deal or get any reward for the valuable clues he gave detectives.

“Some of them say I just want to clear my slate,” Bezzina says.

He set about trying to corroborate Smith’s story with tangible evidence, as he knew that the word of an informer alone can only carry so much weight.

But if he could produce the gun, Bezzina knew he’d have Moran lock stock and barrel.

Smith had pointed out where he believed Moran had thrown the paper bag from the West Gate, and the investigating team calculated its possible landing place.

The search area consisted of about 50 sq metres of river sludge in a high-traffic area of Australia’s busiest cargo port.

Every passing ship sent up silt to further muddy the already murky water, and visibility was zero.

The Search and Rescue Squad scoured the river floor by hand, as determined as Bezzina to find the weapon.

But after a fruitless search lasting several days, Bezzina says he could no longer justify the resources needed to keep looking. The gun could take months to recover, if it were found at all.

“As the investigator, you’ve got to draw a line in the sand,” he says.

It was a setback, but they still had their eyewitness; Smith; some DNA from Kinniburgh, and his demonstrably false story.

There was enough evidence to convince prosecutors, who finally gave them the green light to charge Moran in September 1998.

Dead men don't tell tales

Bezzina was ready to move on his chief suspect when his case was struck a final, fatal blow.

Smith’s body was found outside a church. He’d hoped to redeem himself in some way with his evidence against Moran, but perhaps salvation couldn’t wait. He’s taken his own life.

Dead men can’t give evidence in court, but Bezzina says he still held a lingering hope of charging Moran.

Even that dissipated on June 21, 2003, when Moran was gunned down on the orders of Carl Williams as he sat in a van with his kids at a children’s footy clinic.

Six months later Kinniburgh met a similar death outside his Kew home.

He became the 22nd victim of the gangland war that Moran started when he shot Williams in the stomach in October 1999.

But despite the unwanted attention Moran had brought upon him, Kinniburgh had remained loyal.

“I couldn't see Graham Kinniburgh giving up Jason Moran, because of his association with Lewis Moran,” Bezzina says.

“I think Jason pretty well thought he was pretty safe with Graham Kinniburgh being an eyewitness, that he's going be pretty staunch.

And he was staunch, til the day that he died.”

Follow Charlie on twitter: @HSInvestigator

email: theinvestigator@heraldsun.com.au