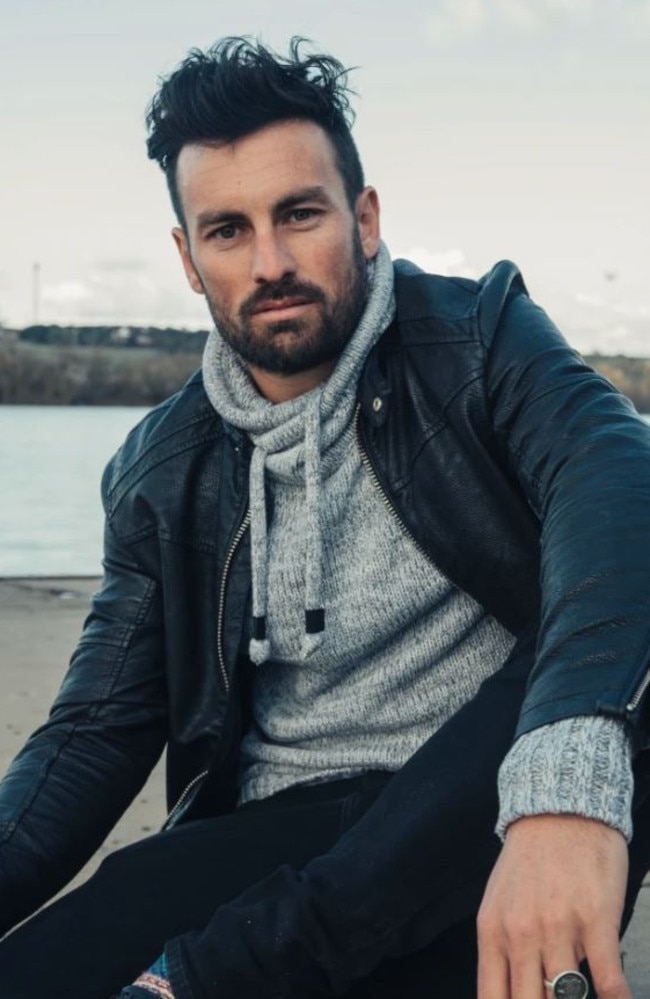

‘I imploded’: Tennis prodigy Todd Ley went from the world’s best to rock bottom

At just 12, Todd Ley was the best juniors tennis player in the world and Australia’s next Lleyton Hewitt, until his world fell apart.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

While Todd Ley was in the thick of it, rock bottom felt pretty good.

He’d spent all of his short life focused solely on tennis, working all day, every day to be the best, at the expense of a normal and happy childhood.

Child prodigies don’t get to have normal lives, he had discovered.

So, when his tennis career crumbled, he did too – and he relished the opportunity to destroy that perfect facade others had forced him to build and maintain at any cost.

“There was no ‘no’ for me,” Ley said of going off the rails. “No such thing. Drinking and partying, all that stuff, was the perfect remedy for me.”

Getting wasted, self-sabotaging, raging and venting felt “fantastic” because being in such destructive state was the most liberated he’d ever felt.

“That way of behaving was completely insufferable, and I was basically teetering on death,” he said.

“Death, jail or insanity. For a long period of time, if you asked anyone, a different life wasn’t on the cards for me. It just wasn’t.”

The making of a prodigy

When he was just 12, Ley was the best-ranked junior player in the world and became the youngest athlete ever signed by famed global sports manager IMG.

He moved from suburban Adelaide to the United States – alone – to train at an academy run by Nick Bollettieri, responsible for a long list of legends of the game like Andre Agassi, Venus and Serena Williams, Monica Seles and Maria Sharapova.

“It’s like a compound for sporting extremists,” Ley said, describing himself as an “inmate” rather than a student.

When not struggling to cope within the confines of the academy in Florida, he was travelling the world to compete in tournaments.

At 16, Ley scored a wildcard qualifier entry to the Australian Open and narrowly lost, shining a renewed spotlight on his extraordinary potential.

The future looked bright for the accidental rising star.

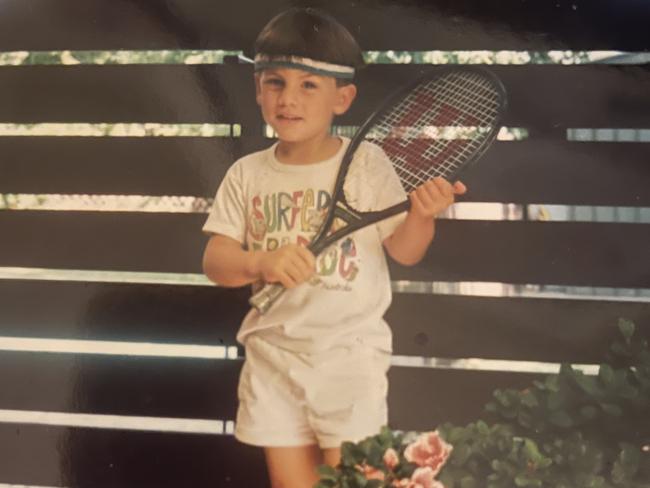

It was a Kris Kringle gift probably bought without much thought – a miniature tennis racquet from an uncle for a toddler to swing around in the backyard – that changed the trajectory of his life.

Ley took to it like a duck to water, and by the age of three, was hitting balls over the net with ease.

“As a kid, I had endless energy and I also liked repetition, doing something over and over,” he said. “And when I’m into something, I get totally lost in it. On top of that, I guess I had a natural talent.”

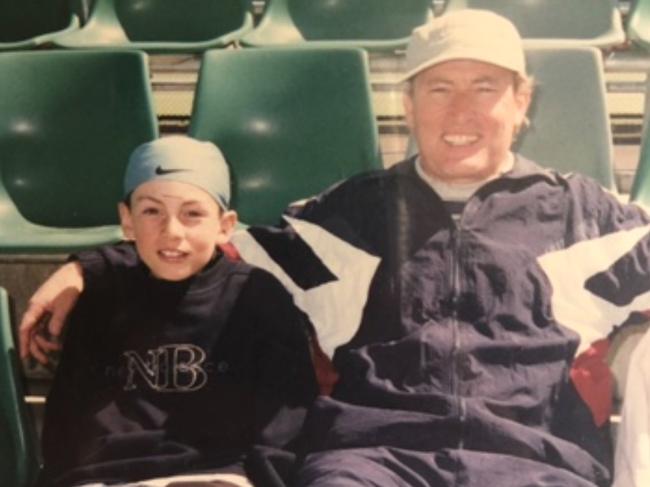

His father Max caught wind of his huge potential and latched onto the youngster as his full-time manager.

The old man had tried his hand at many professional pursuits in his life.

He owned greyhounds, flogged all kinds of wares as a door-to-door salesman, became a real estate agent, and trained his brother as a punter with hopes of landing him an NFL contract in the United States.

But Max was an entrepreneur who never quite found his golden egg-laying goose, until his son’s incredible natural talent presented itself.

“My tennis became priority number one,” Ley said.

As a manager, his dad was equal parts “fantastic and terrible”. An unrelenting taskmaster who was great at getting results, someone who could swing wildly between the roles of jovial mate and prison warden.

From the moment Ley woke each morning until he went to bed again, his existence was entirely about tennis.

“Even when I went to sleep, I had motivational stuff playing in my ears. It was just non-stop. I had no life.

“I was either playing tennis, thinking about playing tennis, or recovering from playing tennis. That was it. There was no off time.”

From Max’s perspective, tennis came first, and his son came a distance second.

“I mean, my nickname was ‘tennis boy’.

“I thought for a while he was doing it for the good of me. And then I could see he was lost in it himself. He was getting some vicarious glory out of it.”

Another troubled tennis dad

When he worked hard and played well, Ley was spoiled, but when he slacked off or didn’t perform, he was berated and punished.

Elite sport – and especially tennis – is littered with horror stories of overbearing parents who push their kids to the extreme to mould – often roughly – the next big star.

ESPN once famously ranked the 10 most harmful family members in sporting history, three of whom were tennis fathers.

The beloved Australian icon Jelena Dokic has described her father and former coach Damir as “the tennis dad from hell”, whose violence and erratic behaviour overshadowed her extraordinary career and meteoric rise to world No. 4.

Similarly, the Women’s Tennis Association has a coaches’ conduct regulation informally known as the ‘Jim Pierce Rule’, named after the man whose horrendous abuse of his star daughter Mary sent shockwaves through the establishment.

Like them and others, Ley’s suffering was a poorly kept secret.

In his view, the tennis machine saw it as a family matter to be handled at home, creating “a convenient loophole” that saw him “slip through the cracks and just get beaten, broken and battered” on his journey to greatness.

“The tennis machine – it will never change. I don’t see it.”

Ley was looked at as a “thing” and not a person – a commodity for others to “exploit” until after drop of potential had been squeezed out.

“Then you get dropped out and you’re wandering around like a broken-down racehorse. It’s better off putting it down because it’s going to be a rough time out there.”

A rapid and dark descent

A lot of buzz surrounded Ley after his appearance at the Australian Open, but he didn’t feel any of the excitement.

He was living “on a knife’s edge” and just about ready to break.

“I was starting to become more and more disturbed by what was going on. I was growing more into my own skin and my own self to some degree.

“I was always under the illusion that if I do well, this is going to get better. And then when [I was] doing better and then the treatment remains the same … it’s like, working hard isn’t getting me anywhere.

“It’s a pressure cooker. So yeah, even though I was doing well, it never felt like I was. It was always very temperamental.”

He was terrified to break the news to his dad that he was quitting.

They went to the pub and over a few schooners, working up the nerve to tell him, Ley expected the worst.

“But it didn’t bother him at all. He quickly went straight on to like, ‘I can teach you to become an NFL punter. You can coach. I can get you to sell pornographic calendars door-to-door with me’. There was a juice he reckoned could cure cancer.

“I realised he was just an extreme person who needed an extreme environment to be in because he found normal living just far too mundane.”

It had never really been about the tennis at all, Ley realised.

“It’s insidious. A lot of parents come into their child’s sport with very pure intentions … they want their child to be successful and prosperous in what they’re doing.

“And very quickly they start investing in their child, and with any investment, people start looking for a return. They completely have a blind spot to the fact the thing they’re investing in is a child. They just lose sight very quickly.”

The wheels came off pretty quickly after that, he recalled, and his poison of choice was “everything”.

“Whatever was going. More of whatever’s going. I just wanted to keep going – I didn’t want to leave where I was. I wanted to stay in fantasy land.

“It was a mess. And I was enjoying it. It felt like I was completely annihilating this image other people had created for me. The feeling of destroying myself was cathartic.

“Because I’d been robbed of a childhood, I felt like I had absolutely every right to make up for what I missed out on. So, I behaved like a child does. And it was fantastic, but also very problematic.”

Somehow, he clawed his way back from rock bottom. Today, Ley is completely sober.

The more things change …

At the highest level, professional tennis offers its players a whole host of welfare and wellbeing resources.

Since Ley’s days, the sport has recognised its obligations and made meaningful steps in the right direction.

But only to an extent, Ley clarifies.

At a grassroots level, where a lot of the damage of overbearing and dangerous tennis parents begins, there’s “nothing to support player welfare”.

Ley now coaches and has encountered the same kinds of fathers that aren’t meant to be tolerated anymore.

When the Damir Dokics of the world are mentioned now, it’s in the past-tense – as though the problems have been successfully rooted out.

“They haven’t,” Ley said. “They’re still around.

“I’ve witnessed it first-hand with players. What I’m saying, it may sound extreme and dramatic. But ultimately, the story I’m telling, I’ve seen happen in so many different forms.”

Working as a coach means remaining inside the machine that inflicted so much hurt and left so many deep scares.

It can be a tough reality to face some days, Ley admitted.

“I need to limit how much I do. I need to watch how much I take on. It is a very dangerous and difficult tightrope that I walk on.

“But with my set of skills and the [limited] things that I can do … I don’t really have that many other options because of the life that I’ve lived.

“I’m not interested in flipping burgers. I’ve got the mortgage to pay. I now have a son, I have a family, I have obligations.”

Ley’s father has advanced dementia and lives in assisted care.

The pair were able to reconcile and become friends later in life, post-tennis, and find some common ground.

Todd Ley’s book Smashed: Tennis Prodigies, Parents and Parasites is on sale now.

Originally published as ‘I imploded’: Tennis prodigy Todd Ley went from the world’s best to rock bottom