When the Spirit of Progress was one of Australia’s great trains

An Art Deco marvel that sped passengers from one end of Victoria to the other in the lap of luxury and in record time, the Spirit of Progress was the crowning glory of a railway visionary and went on to become one of Australia’s greatest trains.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was sleek, thoroughly modern and stacked up with the world’s greatest trains, covering its route at speeds never before seen in Australia and only marginally bested today’s more modern trains.

The Spirit of Progress lived up to its name.

It was Victoria’s own and arrived at the peak of our state’s railway system.

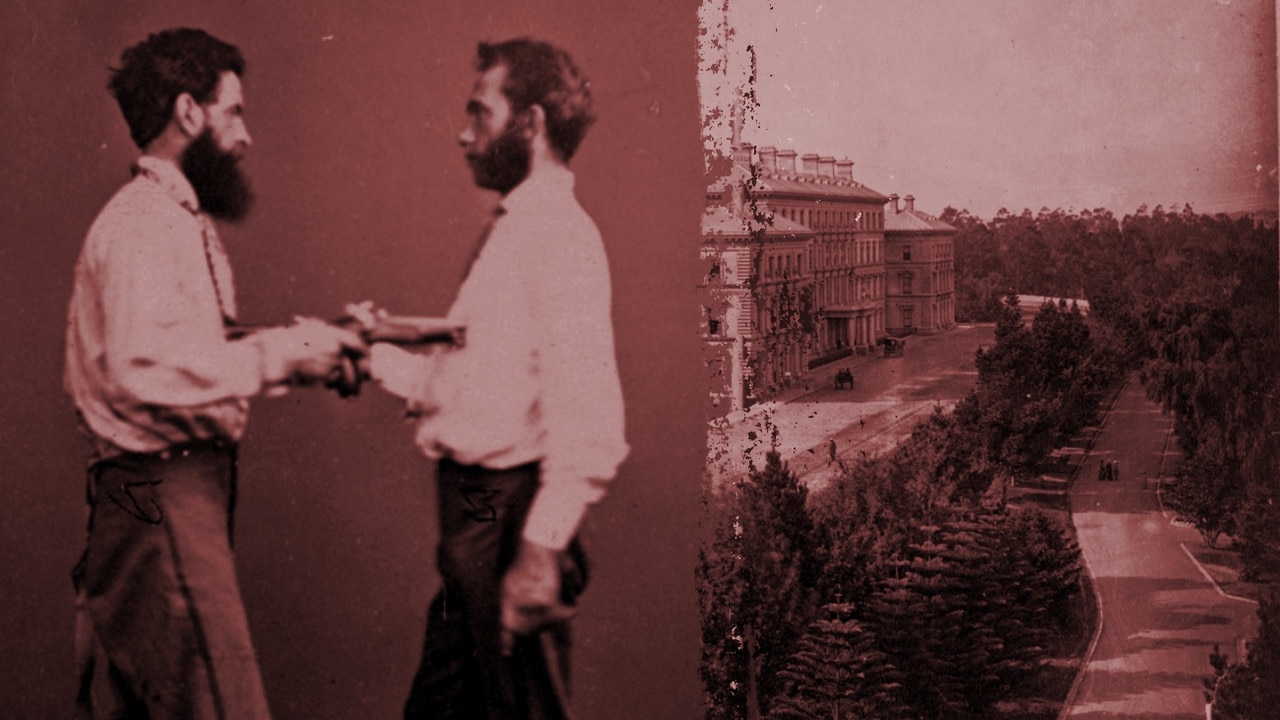

The father of the Spirit of Progress was Sir Harold Winthrop Clapp, who was born in Melbourne in 1875 to Isabella and Frank Boardman Clapp, an American businessman who came out in the gold rush and owned Cobb and Co. Coaches for a time before diversifying into horse-drawn mass transit and tramways.

Young Clapp was a tearaway at school. He completed an apprenticeship in engineering at a firm in South Melbourne and became superintendent of motive power at his father’s tram business in Brisbane before leaving for the US in 1900.

There, he gained great experience in General Electric and in railway companies including an early operator of New York’s subway system before taking the £5000-a-year job as Victorian Railways Commissioner in 1920.

That’s just shy of $350,000 today — and Clapp was worth every penny.

When he returned to Melbourne, Clapp told an interviewer: ”I am all for efficiency and team work and want to know my men and my men to know me”.

True to his word, he was famous for knowing the names of thousands of railway workers and maintained good relationships with union chiefs, at all times consulting with people at all levels on ways to improve the railways.

Clapp used his railway electrification experience to finish the rollout of electric trains across metropolitan Melbourne, made efforts to extend and regrade lines across the state and sped up timetables.

He established a railways bakery to sell food to passengers, especially items that contained dried fruit to support that industry, and established a kiosk at Flinders Street Station that sold fresh orange and lemon drinks to encourage agriculture.

Soon, Victorian Railways had its own butchery, poultry farm and laundry as it improved the standards of services for passengers.

He established the Better Farming Train and the Natural Resources development Train, which travelled to all parts of Victoria to educate farmers and link businesspeople.

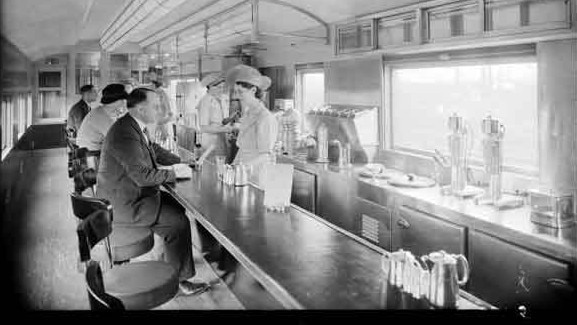

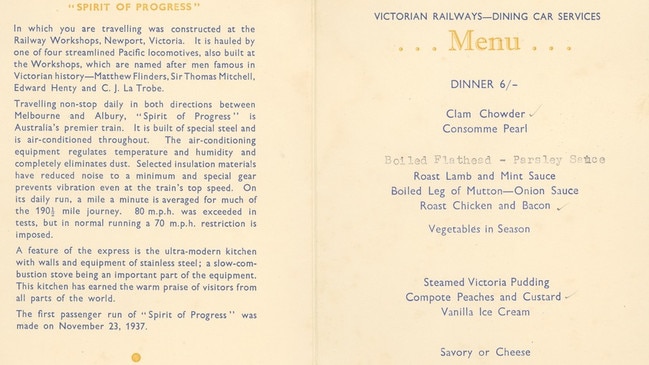

The bakery was soon joined by a railways butchery, poultry farm and laundry. Dining cars were improved and Clapp approved new all-steel buffet cars for passenger amenity.

By 1933, the railways had a creche at Flinders St to allow mothers to come to town and get their business done without hauling their kids around.

His crowning glory, though, came after a fact-finding mission to Europe and the United States in 1934 — the Spirit of Progress.

The Spirit was destined for service between Spencer Street Station and Albury, the most important line in the Victorian Railways empire.

Clapp determined that the old Sydney Limited Express needed to be faster and a modern showpiece for interstate travellers.

The Spirit was built at the Victorian Railways’ Newport workshops.

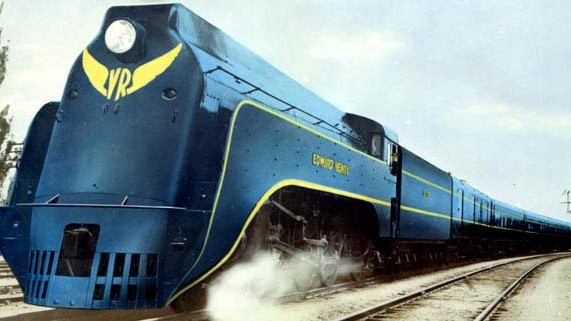

It was an all-steel train, replacing the old timber “dogbox” carriages used in earlier services, and was hauled by one of four sleek S-class “Pacific” steam locomotives, each named after Victorian pioneers — explorers Thomas Mitchell and Matthew Flinders, early pastoralist Edward Henty and CJ (Charles) La Trobe, Victoria’s first Lieutenant-Governor.

The powerful S-class locos had a streamlined cowl that hid the bulk of the boiler and smoke stack beneath a cloak of Victorian Railways blue and gold livery.

It took eight tonnes of coal and 59,000 litres of water for one of those S-class locomotives to haul 555 tonnes including 11 or so steel carriages, 465 passengers, their luggage and the mail non-stop between Melbourne and the break-of-gauge at Albury railway station, 300km away, where passengers would switch to the NSW standard gauge Sydney Limited Express.

Just one S-class loco cost almost $18.3 million in today’s currency.

The lines of the loco blended seamlessly with the carriages, also in VR livery, with double-glazed windows flush with the bodywork and sealed for passenger comfort.

The look was the height of modernity.

It was the same inside. A plush parlour car at the rear, rounded at the back and with a domed roof, allowed passengers to watch the rolling countryside in armchair comfort, with a separate smoking lounge featuring deep leather sofas.

The Spirit of Progress was one of the earliest trains in Australia with full airconditioning, a system tested on other VR carriages up to a year before.

Every carriage was thickly carpeted and heavily insulated, with leather seating and timber features.

Designers searched the world for venetian blinds that would not rattle in the windows of the dining and parlour cars.

The dining car was furnished in timber and leather too, with room for 48 diners at a time, and boasted a stainless steel kitchen with non-slip flooring, coke-fired ovens and a circulating system that reduced the internal temperature and drew cooking odours away from the diners.

State Electricity Commission experts drafted in the design specific indirect lighting for each carriage.

An extra touch for passengers was individual reading lights for each seat.

As construction of the Spirit’s rolling stock took place, major work was underway to strengthen the main northeast line with heavier rails and changes to signals and points.

Once test trains were available, a curious measure was used by engineers to ensure that the line was safe for a maximum speed for VicRail services of 112km/h for the express service.

It was a full bowl of soup in the dining car.

The Spirit was powered up the track above the maximum speed. If the soup splashed over the side of the bowl, the engineers would decide whether to reduce the speed at that spot or regrade a bend to ensure a smooth ride for passengers.

The Spirit of Progress was Clapp’s pet project, and he was intimately involved with almost every aspect of production from the steel construction to the interior fittings.

The response to the new train was rapturous. Ahead of the trains official launch on November 17, 1937, The Argus said: “Streamlining, airconditioning, comfort, efficiency — all are combined in a train the like of which Australia has never seen before. In many features it leads the Empire, and the Empire is interested”.

After an “open house” for the new train at Spencer Street and regional stations including Geelong, Ballarat, Bendigo and Castlemaine, the Spirit of Progress was pressed into service on November 23.

It covered the non-stop 300km Melbourne-Albury run in three hours and 45 minutes, cutting the time elapsed by up to 90 minutes.

The new train was credited with a jump in patronage of 28,000, to 209,000, in its first year of service, and an additional 13,000 the following year. By the end of 1958, the train still carried more than 200,000 passengers a year.

Clapp served the Victorian Railways for another 18 months.

As the clouds of war gathered, he became the general manager of the Aircraft Construction Branch of the Commonwealth Department of Supply and Development, which assembled military aircraft.

RELATED: VINTAGE TRAINS STOKE INTEREST IN HISTORY

SUNSHINE, 1908: ONE OF OUR WORST RAIL DISASTERS

GRANVILLE: HOW 3AW’S KEITH McGOWAN SAW DISASTER

He was knighted in 1941 and, while he never returned to railway service, in 1944 he wrote a report for the Curtin government advocating for rail standardisation across Australia.

Diesel engines had replaced the Spirit’s S-class locomotives by 1954.

Standard gauge railway was completed between Sydney and Melbourne in 1962.

The Spirit of Progress was converted to run on standard gauge but became second fiddle to the new Southern Aurora, taking passengers in the opposite direction to the new train.

As road standards improved and more people could afford to fly between Melbourne and Sydney, patronage fell away.

The Spirit of Progress was removed from service on August 2, 1986. The Sir Thomas Mitchell S-class loco hauled the train for the Victorian stretch of its final run.

A commemorative 70th anniversary Spirit of Progress service, funded by the Victorian government and featuring eight original carriages including the dining and parlour cars, was operated by the Seymour Railway Heritage Centre from Melbourne to Albury, in November 2007.

Recognising the importance of the Spirit of Progress to both Victoria and NSW, the new Hume Freeway bridge over the Murray River at Albury-Wodonga was named the Spirit of Progress Bridge when it opened in 2007.