How did 44 people die when two trains collided at Sunshine in 1908?

IT’S still Australia’s second most deadly railway accident but most of us have never heard of the Sunshine rail disaster that claimed 44 lives.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

AN almighty crash shattered the stillness of the night when a speeding train thundered into the back of another at Sunshine 110 years ago.

The accident, which until the Granville disaster in 1977 was Australia’s most deadly railway disaster, left 44 people dead and up to 500 injured.

Few people remember the crash, but the Sunshine rail disaster left its mark on railway authorities across Australia.

INSIDE THE SLUMS OF 1930s MELBOURNE

THESE ARE MELBOURNE’S OLDEST BUILDINGS

Late on April 20, 1908, two trains packed with passengers were steaming towards Melbourne from Ballarat and Bendigo.

It was Easter Monday, the end of a fine and sunny long weekend, and up to 500 people on each train were heading home after a short country break.

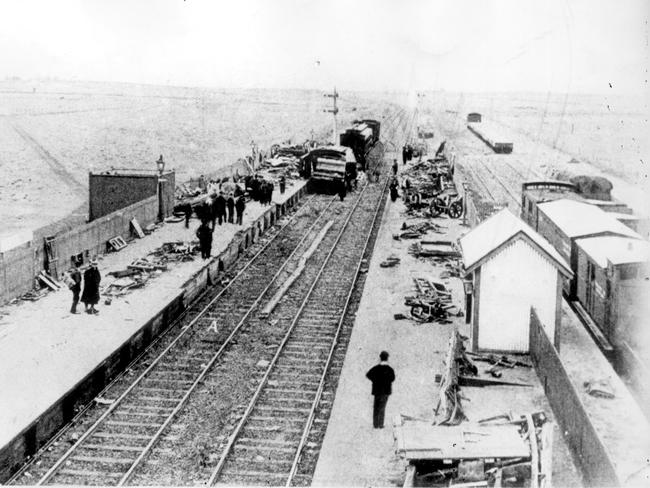

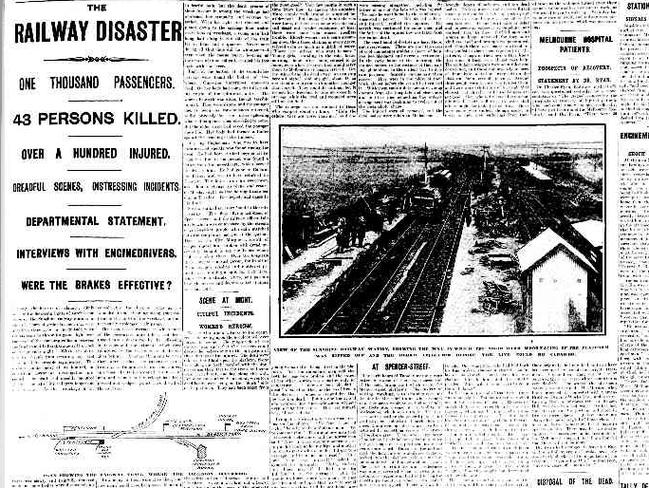

The Ballarat and Bendigo lines converge just north of Sunshine, then a small country railway station.

The Ballarat train was hauling two extra carriages to cater for the added demand.

Both trains were running late and the Bendigo service was operating as an express service to make up time unless passengers indicated they needed to alight before Spencer Street.

Carriages shattered, raining debris across tracks

The Ballarat train stopped at Sunshine about 10.47pm, 43 minutes late.

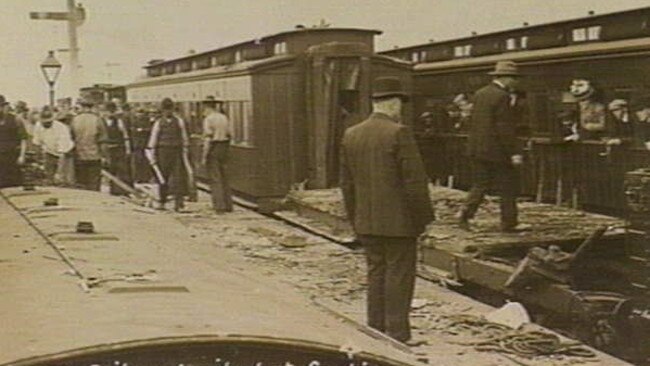

It was just beginning to pull away when the Bendigo train roared in, striking the guard’s van and ploughing through the guard’s van and four timber carriages.

Sunshine and District Historical Society curator Alan Dash says the impact was horrific.

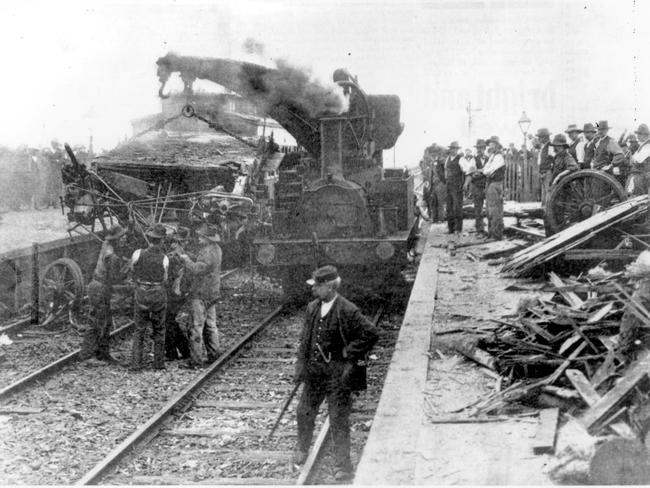

“The photographs of the carriages taken the next day shows there’s nothing of them left. They were wooden carriages and they just shattered to nothing,” he says.

Pieces of the splintered carriages rained across the tracks and both platforms, and a fire sparked by lighting gas hampered initial rescue efforts.

Mr Dash says 19 people died at the scene and between 400 and 500 people lay injured in the wreckage. Another 25 people died later in hospital.

The vast majority of the dead and injured were on the Ballarat train.

The two locomotives hauling the Bendigo train cushioned its passengers. The lead loco suffered only minor damage.

“It’s estimated that there were 1000 people on both trains, so one-in-two people were either killed or injured, depending on where they were situated,” Mr Dash says.

The first of three relief trains left Spencer Street at 12.05am with supplies and rescue workers.

The undamaged front section of the Ballarat train soon returned to Spencer Street, bringing the first of the injured in for treatment at city hospitals.

A steam crane and lighting soon arrived to allow rescuers to work through the night.

A temporary morgue was established at Spencer Street.

Three doctors from Footscray came by horse and buggy to assist. Stunned passengers and the people of Sunshine — then a small factory town for workers at the Sunshine harvester plant — also responded.

“The astounding thing was the quick response of the Railways, and the response by horse and jinker from the doctors,” Mr Dash says.

“I can only imagine the people on duty at the Sunshine railway station must have got on the phones very promptly and the response from the staff of the Railways in getting people there was remarkable in itself.”

Late historian and author Tom Rigg, a former stationmaster at Sunshine, told the Herald Sun in 2008 that his grandfather was a railway repairman who helped at the scene.

“It was terrible. People were decapitated with flying glass,” Mr Rigg said ahead of the 100th anniversary of the disaster.

“There were no axes to cut people free who were trapped in the carriages.

“So many people suffered.”

Who was to blame for the train wreck?

Mr Rigg researched the crash extensively for his book Sunshine Railway Disaster: A Railwayman’s Perspective.

“Sunshine was then a little country station with not many people there,” Mr Rigg said.

“They had no electricity, no doctors, no water, they used kerosene lamps, they had a very difficult time.”

Rescuers had to pick through the wreckage in search of the dead and injured.

“Amidst the ruins … was the dead body of an elderly lady. She died almost as she sat in the carriage. The recumbent attitude, with the grey hairs resting on what once had been a seat, showed how swiftly death had come,” The Argus reported on April 22.

“Within a few feet from her, on the other side, a man was being taken from the ruins. His cries were agonising, but in him there was life, and in life there was hope. The shattered timbers were cut from above, below and round him, and he was lifted out.”

THE UTE: A GREAT VICTORIAN INVENTION

A coronial inquest began in May. It heard that lead driver of the Bendigo train, Leonard “Hellfire Jack” Milburn and second engine driver, Gilbert Dolman, passed a signal at Sydenham indicating an open line and powered on.

They were confronted with a danger signal almost 900 metres from the point of impact.

Milburn reported that he applied the brakes and found them ineffectual, so swung his machine into reverse and applied all available power to slow the train before the collision. A Railways investigation found the brakes were in good order.

The Coronial jury in July 1908 recommended manslaughter charges for the two drivers and the Sunshine station master, Frederick George Kendall.

Charges against Kendall were dropped, but Milburn and Dolman faced the Supreme Court in September.

The Crown alleged Milburn and Dolman passed the Sydenham signal too quickly to stop if the line was obstructed further on, but a jury acquitted both men.

Mr Dash says the drivers were lucky. “Reading what I read, I really reckon they got off light, but that’s only a value judgement and my opinion. I wasn’t there, of course,” he says.

“Why didn’t the train stop? Why was it going so quickly? What happened with the signalling? It was never quite resolved.”

Signals on the approach to Sunshine and the platforms at Sunshine were reconfigured to prevent a repeat of the disaster.

Mr Dash says the disaster was largely forgotten by the general public following Granville, but was high in the minds of railway administrators across the nation.

“Really, the rail authorities of Australia have been very diligent on safety over the years. It took from 1908 to 1977 to have the two big rail disasters, and that suggests that the memory of Sunshine was on railway officers’ minds for many years,” he says.

“Some harsh lessons were learned, and Australia’s rail safety record is pretty good.”

A memorial plaque was unveiled 10 years ago at Sunshine railway station for the centenary of the crash, which remains Australia’s second worst rail disaster.

READ MORE: