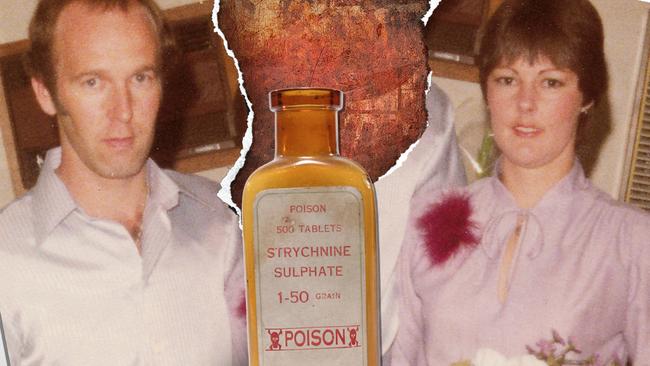

Tragic tale of Rosslyn Truman, a country girl dying to get married

Friends couldn’t understand Rosslyn Truman’s attraction to a man with a thin smile and thinning hair, a wife and two kids. But private reservations and veiled warnings couldn’t save her.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Rosslyn Truman was a friendly, cheerful country girl dying to get married. She got her wish: five years after marrying a man who spent most of what he had on divorcing his first wife, Rosslyn was dead.

Whoever or whatever killed her actually ended two lives. Rosslyn was heavily pregnant with her unborn son when she died in agony.

All that was in the future when Rosslyn decided to get out of Swan Hill after breaking off her engagement to an easygoing boyfriend who wasn’t keen to get married soon enough to suit her plans.

She went off to see the world and got as far as Bendigo, where she worked in a bank and shared a flat in Eaglehawk with her best friend, who’d broken out of Swan Hill the same year.

If Rosslyn had driven to work every day with her friend and flatmate, her life would have turned out differently.

She would, at least, have had a life. But Rosslyn liked taking the bus to work because she liked to sit behind the bus driver and chat.

The driver was Ray McQueen. A thin man with a thin smile and thinning hair, a wife and two kids, but Rosslyn fell for him.

Fell hard enough that when McQueen’s long-suffering wife knocked on the door one day to ask her to stop trying to steal her husband, it didn’t work.

Be careful what you wish for, the saying goes. The divorce cost McQueen most of what was left after he and his first wife left farming near Beulah, in the southern Mallee.

After being “let go” by the bus company, the one-time wool classer and keen country tennis player took up selling life insurance for National Mutual.

Not everybody shared Rosslyn’s confidence in the insurance man. Her friends were polite about him but couldn’t understand the attraction.

“I never took to Ray McQueen. He made my skin crawl,” Rosslyn’s former flatmate recalled this week.

“He was mean to her.”

That view, it turns out, was shared by others who swore on a Bible in court before expressing them.

But private reservations and veiled warnings didn’t help Rosslyn, whose world ended at breakfast time on April 1, 1986. April fool’s day.

That morning, Ray drove off just before 8am as he usually did to go to work in Bendigo.

On the way, he picked up Donna M, the teenage babysitter he was infatuated with and supposedly teaching to play tennis.

He drove her all the way to the shop where she worked. But he was quiet and distracted, according to Donna’s later evidence.

At work, he made a show of having to call home to check on details of some supposedly forgotten paperwork.

When no one answered, he called the closest neighbour, a kindly older man named Vin McKenzie.

The coroner would later describe both McQueen’s calls as a “ruse”.

The obliging McKenzie checked the McQueen house and discovered Rosslyn’s body, arched over a stool, spine rigid as if she had died convulsing.

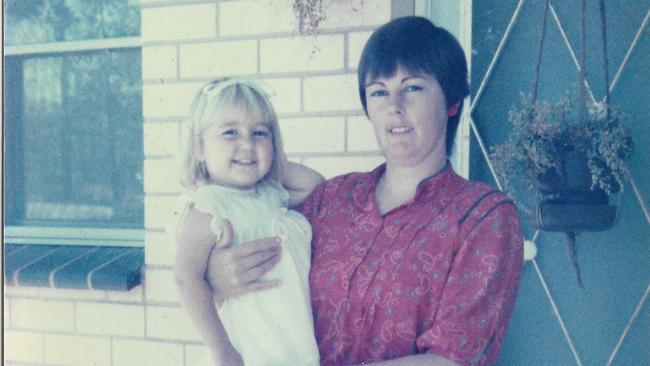

Her little daughter, Jodie, not yet three, was babbling something McKenzie later recalled as “Mummy’s dead and Daddy’s gone to work.”

The shocked McKenzie called McQueen, the ambulance and police.

When they all arrived, Ray pointedly told police Rosslyn had “cancer”.

But a doctor who checked the body refused to sign a standard death certificate for the apparently healthy 31-year-old woman. Meaning her death was referred to the coroner for post mortem.

By the time the pathology results came, Rosslyn’s body was buried in Kangaroo Flat cemetery.

The toxicology report showed that she had died of severe strychnine poisoning after ingesting five times the lethal dose.

The homicide squad arrested Ray McQueen and charged him in the first week of July — three months after his wife’s death.

An inquest began at Eaglehawk Court. The coroner, Geoff Hoare, would make his finding almost exactly a year after Rosslyn’s funeral.

The finding ran to 16 pages but the coroner’s points are plain and easily summarised. He agreed with the prosecutor, Nigel Parkinson, and detectives Ron Blackshaw and Mick Furlong, that troubling aspects of the story pointed to foul play.

Firstly, there is motive. In this case, it can be summarised as sex and money.

Several witnesses gave evidence that the 34-year-old McQueen was infatuated with the troubled teenager, Donna, who often stayed at the McQueen house and played tennis with him.

One witness, Debbie Wiegard, testified that she’d seen Donna with her head in McQueen’s lap in a car near the local tennis courts.

The court heard that McQueen asked Donna to move into the house with him days after Rosslyn’s death and proposed marriage soon after.

Then there’s the fact that Rosslyn’s life was insured. If she died, it was worth up to $17,000 to her husband — a year’s wages for a rural worker.

But if she lived and McQueen went through another divorce so close to his first, he would be stripped of almost all remaining assets. So a dead wife, financially speaking, would be a double win for him.

McQueen had mentioned to a work colleague not long before that he’d wanted to raise his wife’s life policy to $60,000 but couldn’t because of the “cancer” diagnosis. This implied he was preoccupied by both the possibility of insurance payouts and of a terminal disease.

Did an alleged killer have opportunity?

There were no other adults or children old enough to be witnesses living with the McQueens. Their house was in the country, on a generous block separated from its neighbours. Rosslyn’s family did not live locally and her friends were in Bendigo.

Thirdly, the means to murder. Though it was ultimately too difficult for investigators to prove to the necessary standard — beyond reasonable doubt — the coroner would conclude that on the balance of probabilities Ray McQueen had the means to poison his wife.

Other strands of circumstantial evidence support the coroner’s murder hypothesis. McQueen’s strange insistence that his wife had died of cancer was clearly not only inaccurate but insincere.

Just four days before her death, a specialist had assured her that she did not have cancer — meaning that a GP’s earlier suspicion that she might have cancerous cervical cells was wrong and that she would be able to have her baby safely.

This cheerful diagnosis, the coroner found, was good news for the pregnant woman — but calculated to upset secret plans her husband had already formed about taking up with Donna after Rosslyn succumbed to her supposedly fatal illness.

The sudden change of Rosslyn’s diagnosis coincided with a trip to see friends in the Mallee on the Easter weekend before she died.

The Mallee trip included a visit to see McQueen’s friend and former neighbour Paul “Warts” Boehm, who had grown up on a nearby farm in their home district near Beulah.

The significance of the Easter visit, the coroner found, was that it reminded McQueen of a farmyard incident years earlier at Beulah in which a tin of strychnine had spilt and killed several of the Boehms’ pigs.

The implication was that a trip to the Mallee that weekend meant it was likely that McQueen could obtain strychnine, commonly used by farmers like his own family to poison pests and wildlife.

The coroner dismissed any possibility that Rosslyn McQueen had accidentally been poisoned, or that some unknown person had administered strychnine.

He also found it overwhelmingly unlikely that she had committed suicide.

There was no evidence she was suicidal. But even if she had been, she had far easier options, such as “gassing” herself using a car exhaust, taking an overdose of sleeping tablets or even shooting herself, using her husband’s gun.

For her to be able to obtain strychnine and use it without leaving a trace was so implausible it was safe to rule out, the coroner found.

Rosslyn — not raised on a farm using poisons the way her husband was — had no knowledge of strychnine and no way of obtaining it. In any case (according to the coroner), a suicide scenario was unlikely, given that Rosslyn had just received good news about her health, was looking forward to her son’s birth, and would hardly kill herself knowing her tiny daughter would be alone all day.

The circumstances all seemed sinister. The coroner noted that Rosslyn took iron supplement capsules each day, meaning it would be relatively easy for someone to fill a capsule with strychnine to ensure she willingly swallowed it whole. The capsule would mask the poison’s bitter taste until it dissolved in her stomach, giving a poisoner time to flee the scene.

In other words, the coroner agreed with the prosecutor that every strand of circumstance indicated murder or manslaughter, not suicide or accident.

He wrote: “One reasoned and reasonable hypothesis (is) that she was poisoned in some way, with malicious intent, by her husband.”

But if the death of Rosslyn McQueen struck many people as something like a perfect crime, it was not the perfect crime investigation.

Which meant that when Kevin Raymond McQueen’s trial was finally scheduled to begin in the Supreme Court at Bendigo in June 1988, the family and friends of the dead woman were in for a shock.

Just days before the trial was to open, a spokesman for the Director of Public Prosecutions dropped a bombshell: the prosecution was quitting the case because it believed there was not enough admissible evidence to put before a jury.

The legal term for this is “nolle prosequi”. Withdrawing the charges did not mean that the accused man had been acquitted, the lawyer explained. But it did mean that experts believed there was no likelihood of a conviction because of the nature of the evidence.

What wasn’t said but seemed clear was that investigators had a gap in their otherwise compelling case: they could not show how strychnine came to be in the McQueens’ house, thus providing the “smoking gun” the prosecution needed to harden the web of circumstantial evidence.

The reasonable assumption that someone like Ray McQueen could covertly obtain strychnine in the farm districts of his youth was not the same as proving it.

McQueen erected a small black headstone on his second wife’s grave. It says “May you find comfort and peace in the little boy you carry. Love Ray.”

Donna the babysitter rejected his advances and moved interstate, far from Bendigo and the stares and whispers.

Soon after, McQueen married his third wife, Carmen. They moved to Melbourne and still live quietly in the outer northern suburbs.