The mystery of a truckie shot dead by a sniper

Bendigo truckie and keen punter Kevin Pearce didn’t stand a chance when a sniper opened fire with a high-calibre weapon powerful enough to hunt big game.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Killers do all the dumb things. They kill for stupid reasons, from the petty to the perverse to the pathetic.

Loss of face, an old grudge raked over, a flash of temper, jealousy or blind greed. Add alcohol or drugs and any one of those can lead to senseless murder, wildly out of proportion to the risk of a life sentence.

But none of those things applies to the cold-blooded shooting of Kevin Pearce as he loaded his truck at Bendigo late one night in 1985 ready for his Mildura mail run.

At 45, Kevin Pearce was no tough truckie, just a harmless family man doing the best he could.

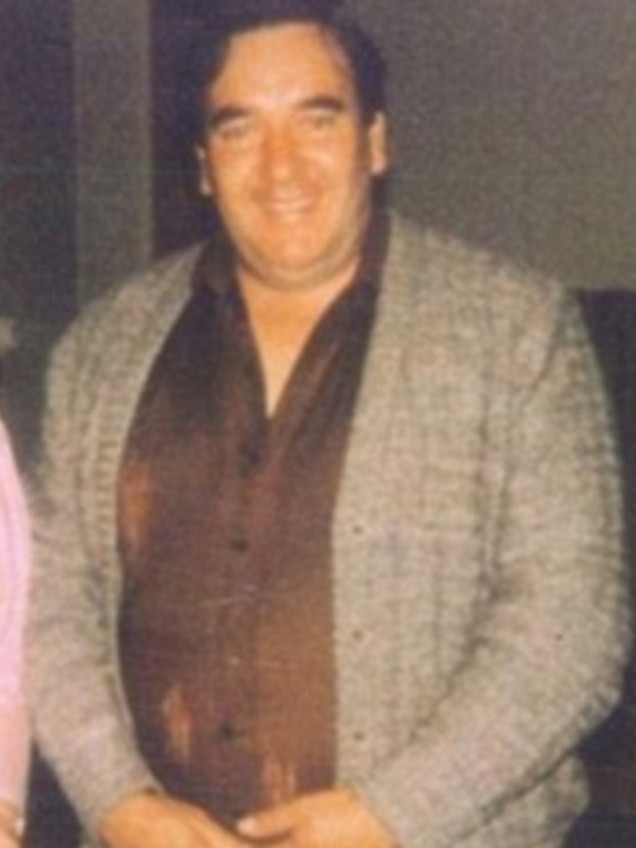

But the younger man that a coroner later named as causing Pearce’s death was tougher altogether, and the two had fallen out over money. His name was William James Matthews, known as Bill.

One aspect of the relationship that certain local police should have known about but homicide investigators probably didn’t, was that Pearce was an habitual punter — and Matthews was one of two SP bookmakers in Bendigo apparently “tolerated” by police.

Habitual gamblers lose over time, which leads to unpaid debts, and those who knew both men suggest that Pearce bet and lost more regularly than his wife and family suspected.

His wife Joan ran the family milk bar and queried why she was working seven days a week to subsidise the apparent continual loss-making of the truck business.

Whatever caused the friction between Pearce and Matthews, it turned deadly in 1985.

Just before midnight on April 15, Pearce was loading cargo in his truck at McPhee’s transport depot in Bellevue St, Golden Square, when a heavy calibre rifle boomed in the darkness.

The .308 bullet, a semi-military round heavy enough to hunt big game, smashed Pearce’s arm and blew a hole in his side. The wound was so big that fellow drivers jammed a roll of toilet paper in it to try to stop the bleeding.

Pearce’s wife, intending to keep him company on his overnight run, had been waiting a few blocks away at the Bendigo Mail Centre for the Melbourne mail truck. She heard the shot just before the truck pulled in and screamed at the driver, “For God’s sake, take me there!”, pointing up the road to McPhee’s.

“When I got to Kevin, lying on the ground, he said: ‘The bastard got me’.”

If Kevin Pearce had died then, the homicide squad would have come immediately and the investigation might have ended differently. But he survived the ambulance trip to the Austin Hospital and clung to life for another three weeks.

Joan and their three daughters got to say goodbye. But Kevin’s lingering death meant the trail of the killer had gone cold before the mystery shooting became a murder investigation.

No one has yet suggested that local detectives took short steps or missed clues and cues, but the results were disappointing for the devastated Pearce family. Mainly because there weren’t any.

By the time homicide investigators arrived, the trail was nearly a month old and getting cold. Local police had been all over the scene, muddying it without finding much. Witnesses had time to muddle their recollections, potential suspects had time to get their story straight.

But there was never any doubt that Joan Pearce and everyone else present knew which “bastard” the wounded Pearce meant. Everyone knew that Matthews had taken a violent dislike to Pearce.

At the time it was accepted, for good reason, that the enmity was because the pair, former partners in a freight delivery business, had argued over a large amount of fuel taken from a shared bowser.

After Pearce went to the police over the apparent fuel theft, he was warned by mutual acquaintances that Matthews was after him. But people in the local racing fraternity (in which both men mixed) saw the missing fuel as part of a bigger picture, probably involving gambling debts.

Whatever his reasons, Pearce became so nervous that he sometimes got his daughter Donna to follow his truck in her car on his nightly run. He told her that if he didn’t return from unloading mail behind country post offices late at night, to go straight for the police.

At a family wedding only weeks earlier, Pearce told a relative who was in the police force, Roger Irwin, that he’d heard Matthews was gunning for him. But police couldn’t act until an offence had been committed.

The homicide crew who got the job confirmed that the shooter had lain under a tree 44m from where Pearce was shot. Police had found several cigarette butts at the spot, and these would become of great interest 20 years later, when new DNA testing identified them as belonging to a young woman employed by Matthews, Dianne Robertson.

Investigators were not sure that Robertson had necessarily been with the shooter. It seemed just as likely that someone had planted her John Player butts to make it look as if the shooter were a smoker, which Matthews then allegedly wasn’t.

If the butts were deliberately planted, the ruse eventually backfired when DNA testing later confirmed the link with Matthews — reinforced by the fact a yellow car like Robertson’s was seen leaving the scene.

The then very young Robertson was mired in Matthews’ complicated private life. He had left his wife Mary, mother of their three children, to live with his de facto, Keryn Strawhorn. But while Strawhorn was having a baby he was intimately associated with Robertson.

Matthews was busy in other ways, too. Pearce had told family members that Matthews ran an SP book, and that he sometimes bet with him.

Punters who run up credit bets with illegal bookmakers can suffer reprisals. Murder is rarely one of them. But, as long as there have been bookies, there have been heavies to collect betting debts.

Matthews’ alleged SP bookmaking implied inside knowledge of a racket with underworld and corrupt police connections. Alert detectives would have noted the coincidence that his de facto wife’s rare family name is shared with former disgraced drug squad sergeant Wayne Strawhorn, sentenced to seven years in 2006 for drug racketeering.

One reason Pearce was nervous of Matthews after going to police about the missing fuel was (he told his wife and daughter) that Matthews had once casually discussed paying “a couple of grand” to harm another man over a financial dispute.

If Matthews was operating an SP book, and impeccable sources say he was, the fact he (and one other SP bookmaker in Bendigo) could operate with apparent impunity guarantees he was on close terms with at least one influential local police officer.

Persistent gossip, never substantiated, was that drugs or other contraband could be transported on the mail truck runs. The theory was strong enough that police stripped Pearce’s truck after the shooting, looking for contraband. They found nothing.

Pearce was against drugs and warned his daughters against them in strong terms. His daughter Donna is convinced that if her father were being stood over to ferry drugs to or from Mildura, he would refuse. But he had the mail contracts for the Mildura and Echuca runs and, according to the Pearce family, Matthews wanted them.

What at first seemed the most damning evidence against Matthews was that Pearce was shot with a .308 rifle using Musgrave brand ammunition — and Matthews had a .308 rifle (and Musgrave ammunition) stolen from a Footscray truck loading bay the year before.

Police had found an empty Musgrave .308 shell at the shooting site. They knew that the obedient Dianne Robertson had contacted another truck operator, Barry Coates, to get rid of a rifle and ammunition hidden in his backyard. Coates threw the rifle into Lake Eppalock but his daughter told police, who retrieved it.

It seemed like the “smoking gun” but it wasn’t. Ballistics experts said the shell found at the crime scene did not match shells test-fired from the Matthews rifle fished from the lake. Detectives were staggered by the coincidence that Matthews had got rid of a .308 rifle after Pearce was shot, yet it had not proved to be the murder weapon.

To be fair, it was logical that Matthews would be wary of being caught with a stolen firearm and would want to hide it.

The investigators might have wondered if anyone cunning enough to plant cigarette butts as a red herring might also be cunning enough to plant an empty shell from a different rifle.

Matthews did not have a watertight alibi for the exact time of the shooting. He had the means and at least one motive for murder. Both he and his secret lover Dianne Robertson refused to give evidence at Pearce’s inquest in 1986 on grounds of self-incrimination.

The coroner, Hal Hallenstein, said Pearce was killed by someone who knew his routine. He found that Pearce was “shot by or by the arrangement and organisation of William James Matthews.”

Matthews was committed for trial but the case was later withdrawn for lack of admissible evidence.

Two homicide detectives, one of them female, went to Queensland recently to speak persuasively to the middle-aged woman who used to be a frightened girl named Dianne Robertson. The squad is working with a television program highlighting murder cases for which there is a $1 million reward.

Those who know Bill Matthews say he is not looking forward to the Kevin Pearce episode. Someone, somewhere, might know enough to take a chunk of the million dollars.