Sinful pleasures, sickness: the sensational secrets of early Melbourne

TIME and 19th century austerity have hidden some of Melbourne’s darkest secrets. Back in the day, Melbourne was a hotbed of sinners, sickness and scoundrels.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

LADIES (and men) of the night, outbreaks of infectious diseases and one of Melbourne’s most audacious thefts were all part of the colour of Melbourne in the 19th century.

Here are a few of the dirty, long forgotten little secrets that set Melburnians abuzz in the 1800s.

PLEASURES OF THE FLESH

Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet, were part of the seediest parts of early Melbourne.

MORE VICTORIAN NOSTALGIA:

FADED HOUSEHOLD GEMS THAT BRIGHTENED AUSSIE HOMES

VICTORIAN PLACE NAMES THAT DON’T SEEM TO MATCH

Present-day Crossley and Liverpool streets, parallel lanes running from Bourke Street to Little Lonsdale Street between Spring and Exhibition streets, were once named Romeo Street and Juliet Terrace respectively.

SEE THE DODGY 1982 LUNCH MENU THAT FED A MELBOURNE PRIMARY SCHOOL

Officially, the nearby Shakespeare Hotel was the inspiration for the names, but these took on a new meaning when the lanes became one of Melbourne’s early red light districts.

Ladies of the night plied their trade in Juliet Terrace, and their male counterparts frequented Romeo Street.

The whole area was a hotbed of crime, drawing Melbourne’s underclass for an orgy of criminal enterprises in an area known unofficially as Bilking Square. Bilking was a colloquial term for cheating someone of their money.

Members of the oldest profession in that part of town had a habit of stealing their patrons’ wallets — a crime that was difficult to report in such austere times.

The Melbourne City Council was keen to end the area’s seedy reputation.

In 1876, it renamed Romeo Lane as Crossley Street in 1876 and, 14 years later, Juliet Lane became Liverpool Street, but many of the brothels remained until after World War I.

DID THE MISSING MACE GO TO THAT PLACE?

Victoria’s Parliamentary mace disappeared in 1891, never to be seen again, and it’s long been rumoured that it somehow found its way into a brothel near Parliament House.

Back then, you could have chucked a rock from the top of the steps hit the roof of a brothel in the Bilking Square precinct.

The mace, a symbol of the Parliament’s power and authority handed down to us through the Westminster system, is used by the Parliament’s Sergeant-at-Arms to lead the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly.

Up to the reign of Elizabeth I, it was used as a weapon by Westminster’s Sergeant-at-Arms to protect the Speaker of the House of Commons and maintain order and security in the chamber.

Victoria’s original mace, a timber one used when the Victorian Parliament was opened in 1857, was replaced with a far more ornate and valuable model made of gold and silver in 1866.

The mace had a Maltese cross at the head and was engraved with the Victorian and English coats of arms.

The Assembly used it from 1866 until it was famously stolen from its box in the Speaker’s office in 1891. Despite a widespread police search and several suspects, including the then Speaker, it was never found.

Around 1.30pm on October 9, 1891, at the beginning of the great 1891 depression, the mace was stolen from a locked box in the speaker’s office.

Theories abounded. A sozzled MP may have taken the mace for a lark and lost it.

The speaker (and future premier), Thomas Bent, and the parliamentary engineer, Thomas Jeffrey, were accused.

A tradesman working on extensions to the building may have swiped it, or an opportunistic thief may have grabbed the mace when no-one was looking.

But the press had a far more salacious theory — that it wound up in a nearby house of ill repute.

This captured the imagination of Melburnians and remains the most famous theory to explain the mace’s disappearance even though an 1893 inquiry dismissed the very idea.

The mace was never recovered. In 2001, the reward for the return of the mace was increased to $50,000.

CRIME AND DEBAUCHERY: THE DARK PAST OF MELBOURNE’S LANEWAYS

MELBOURNE: TYPHOID CITY

In an era when Melbourne grew into a grand, modern city thanks to Victoria’s gold wealth, typhoid killed thousands.

It is a bacterial fever that can be highly contagious and presents itself with red spots that erupt on the chest and abdomen.

Typhoid and paratyphoid can be transmitted through contaminated water or food, or by fecal-oral contact. Most of the 30 typhoid and 20 paratyphoid infections treated in Victoria each year are contracted overseas, but in the 19th century Melburnians had some filthy habits.

The city, nicknamed Smellbourne by some, was awash with raw sewage from cesspits and open drains.

Night-carters would use the back lanes of the city and suburbs to collect waste from residents’ outdoor dunnies, but they’d often dump what they had collected from the city’s thunderboxes into the streets.

In the years from 1869 to 1878, 1172 people died in Melbourne from typhoid fever, with the rate accelerating sharply from 1874 on. In 1871, Melbourne’s population was around 200,000.

Over the period, deaths were recorded all over metropolitan Melbourne but dozens of cases occurred in Hotham (present-day North Melbourne), Carlton, Collingwood, South Melbourne and Emerald Hill.

Typhoid-related deaths continued into the 1880s.

As the connection between infected water and typhoid became clearer, the city’s leaders began to act. The Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works was formed in 1891, and by 1898 Melbourne was connected to the Werribee treatment plant via a pumping station at Spotswood.

QUIT SPITTING

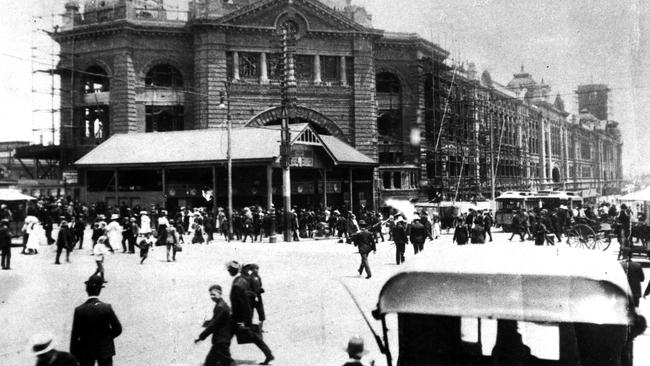

Those “do not spit” signs in the Flinders Street railway viaduct weren’t just there to prevent slips.

Apparently, it was quite common in the 19th Century for folks to spit and publicly perform a range of bodily functions frowned upon today including public urination and passing wind.

The push to stop public spitting was not about its unsightliness but the discovery that the habit might have contributed to the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis.

Happily, although most of us don’t spit these days, the “do not spit” signs will survive the $100 million redevelopment of Flinders Street Station.

MARKET AT DEAD END OF TOWN

Next time you pop into Queen Victoria Market for your fruit and vegies, and maybe a Spanish doughnut from that van in Peel Street, you might be walking right over up to 9000 bodies.

Melbourne’s first general cemetery was located in the southern part of the market.

The cemetery was established in 1837 and was closed in 1854 but burials to reunite loved ones in the afterlife were allowed there as late as the families had vaults or reserved allotments. It was divided into various religions, with a separate section for aborigines.

John Batman, one of Melbourne’s founders, was buried on the site, and a cairn in his honour remains at the market.

Over the years, the market was extended across former cemetery land, with new sheds and the southern car park constructed over the top.

Exhumations of marked graves began in 1920. There were 914 bodies shifted from marked graves in all, leaving the remains of about 9000 people still beneath the market.

There are other graves in central Melbourne. A short stroll from the market at Flagstaff Hill (once known as Burial Hill), where four adults and three children were laid to rest between 1836 and 1837.

There is no records that the bodies were exhumed, so historians believe the seven remain there.