Melbourne’s Docklands: Industrial wasteland to new suburb in 20 years

THE Docklands has been transformed from industrial eyesore to skyscraper suburb in the space of 20 years. Take a look back at how much it’s changed.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

MELBOURNE’S Docklands was once buzzing with hundreds of dock workers and ships unloading cargo from across the seas.

The Docklands thrived as the city’s busiest port until the 1950s, when a new port was built further down the river that better suited deliveries from container ships.

A decade later it was a forgotten industrial wasteland.

Take a look back at the history of Melbourne’s Docklands as it was transformed from an eyesore into a new suburb in the space of 20 years.

MELBOURNE’S PHANTOM TRAIN LINES

Before European settlers arrived in Melbourne, the Docklands area was wetlands with a salt lake and a large swamp.

One of the city’s founders, John Batman, set up his home on Batman’s Hill in the Docklands — but the area remained largely unused for decades.

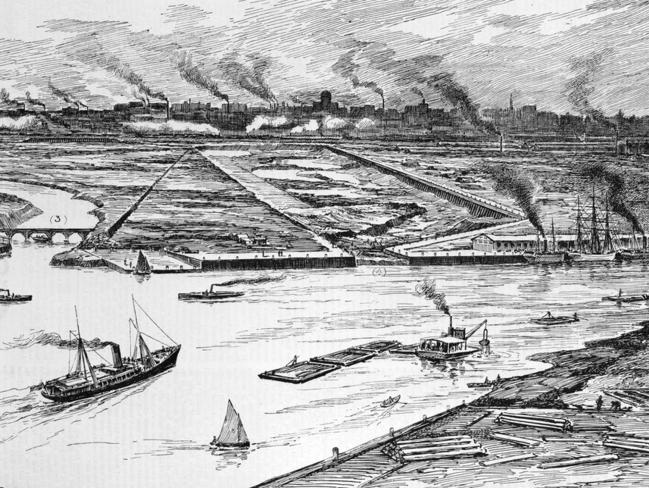

By the 1880s there were major engineering works underway to reroute the course of the Yarra River to make it wide enough for shipping.

THE MELBOURNE SUBURB NAMES THAT WERE SCRAPPED

It was lined with wharves and became a shipping hub, and by the 1920s Victoria Dock and the surrounding port had become Melbourne’s busiest.

It was the main port used for naval vessels, with most of the Victorian troops returning from world wars unloading at the docks.

HOW THE ICONIC GREAT OCEAN ROAD POLE HOUSE GOT BUILT

The old docks weren’t large enough for container ships, and in the 1950s shipping was moved further down the Yarra to east of where the Bolte Bridge sits today.

The Docklands went from bustling port to vacant land, and by the 1980s governments were looking at ways to make use of the land — which would continue to sit idle for a further decade.

A Docklands taskforce was set up in 1990 and by 1991 by the Docklands Authority was developing strategies try and reconnect the site to the city.

The challenge was to unlock an area that was hidden from the public and make it a useful and desirable location.

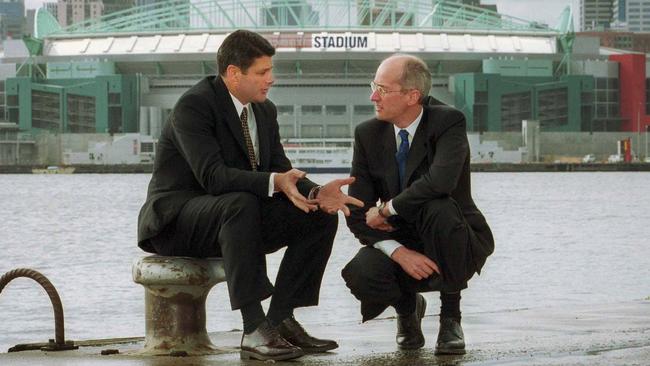

From 1993, the Kennett Government adopted Docklands as part of its plan to revitalise Melbourne and in 1995 proposals were sought from the private sector for seven precincts, including residential, commercial and recreation areas.

By 1997 the first development agreements were signed for Etihad and the Yarra’s Edge development and the stadium construction began.

Around 20 developers were short-listed by the Kennett government for major projects but most of the tenders fell through and much of the development stalled.

In 2000, a newly elected Steve Bracks government released a new tender for Docklands development and a period of rapid high-rise building began.

Etihad Stadium and the La Trobe and Bourke Street bridges opened the same year, and construction began on the first apartments, with the first tower completed in 2001.

By 2003 the City Circle tram extended through Docklands and a year later the Collins Street Bridge opened — extending Collins Street into the Docklands.

Docklands was home to three Commonwealth Games events in 2006 and a stopover point for the Volvo Ocean Race.

Most recently the retail precinct, Harbour Town Shopping Centre, opened its doors in 2008 and the Melbourne Star Observation Wheel was switched on in 2013.

Other big-ticket tenants include superstore Costco, dual Olympic-sized skating rinks at Icehouse, as well as ANZ, NAB, Myer and Channel 7 and Channel 9.

The retail and leisure sites at Docklands have been a struggle for governments and the precinct is often under attack for its alleged lack of charm, lack of greenery and terrible traffic congestion — and the ever present wind tunnel effect.

Despite being on the city’s doorstep, it is still perceived as inaccessible and still remains a mystery to many Melburnians — although there are 10,000 people that call the Docklands home.