Sam Fisher turned up to the County Court a couple of weeks ago with a dark suitcase.

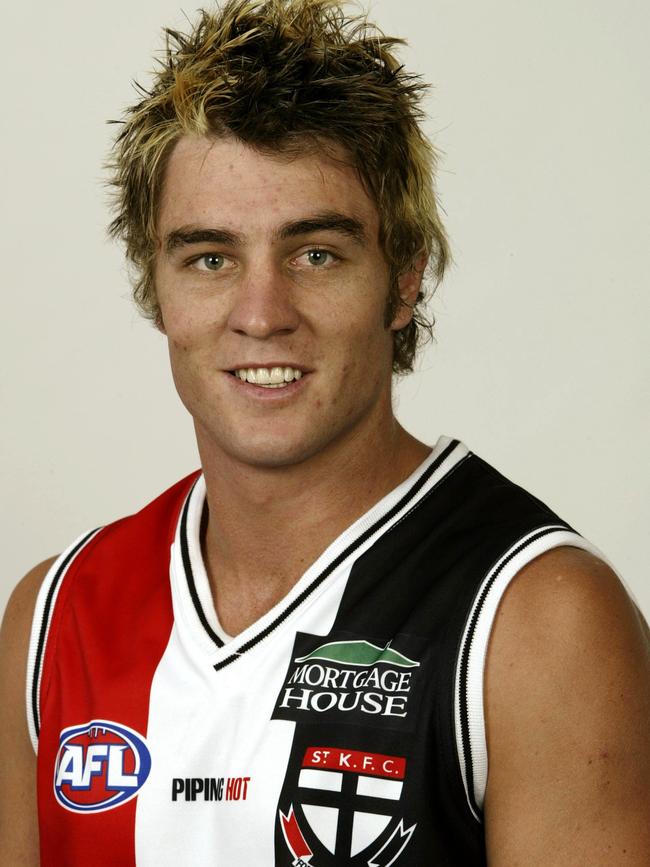

He wore a tie that looked to be borrowed, and an expression that made him look much older – and yet also much younger – than his 41 years.

If he was fuller of body, he was smaller of spirit. Surely this wasn’t the person whom St Kilda football fans once bowed to in times of stress?

Fisher dabbed at tears. His chin trembled. He was a condemned man going to jail.

This Thursday, he will turn up to court again, almost certainly with that suitcase, to project that odd mix of lost little boy and hardened junkie.

This time, there will be no more legal delays or chances to ponder his choices.

This time, Fisher will go to jail.

Everyone agrees that he should. He trafficked hard drugs, in a plot which sounded more elaborate than some misplaced impulse of opportunism.

Yet can we also hope for green shoots from his grim fate, albeit on a day that may stand as the worst of many bad days since Fisher retired from AFL football in 2016?

Stripped of his AFL star status, Fisher’s downward arc seems tawdry. He dabbled in drugs for a long time. As early as 2012, he was denying a newspaper report that his “controversial behaviour has begun to antagonise his teammates”.

In 2013, in an interview noted for his boyish ease, he denied using drugs, even arguing that such suggestions were upsetting his parents back home in South Australia.

Football was over for Fisher a few years later. He dabbled more, and discovered that a non-footballing life offers few safety nets.

He ran out of money. Jobs didn’t stick.

From afar, it seems he turned to drug trafficking to fund an isolated existence. Once famed for his unassuming lust for fun, he shunned friends and family. His core shrunk to a daily buzz of GHB and methamphetamine.

There was talk of a nasty break-up. He was a “bit lost”, as he later called it. The years of stardom faded fast.

One newspaper report had him asking St Kilda for money after he retired.

Another, citing his long-time coach Ross Lyon, had his ex-teammates trying to stage an intervention.

Fisher was bad news, even by the sometimes excessive trappings of sporting celebrity.

Enforced retirement in 2016 should not have surprised Fisher. Injury had limited him to 61 games in the five years before. After years of gritty service, his salary was pegged to the number of games he could play each season.

He was 34, and had trialled a couple of workplaces for a football-free future. Yes, he wanted to play footy forever – who wouldn’t? And like so many people, when they are denied their symbiotic sense of work, he lost his identity.

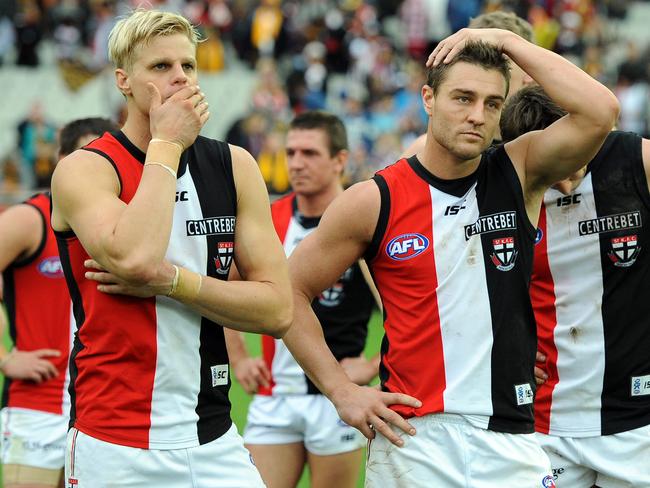

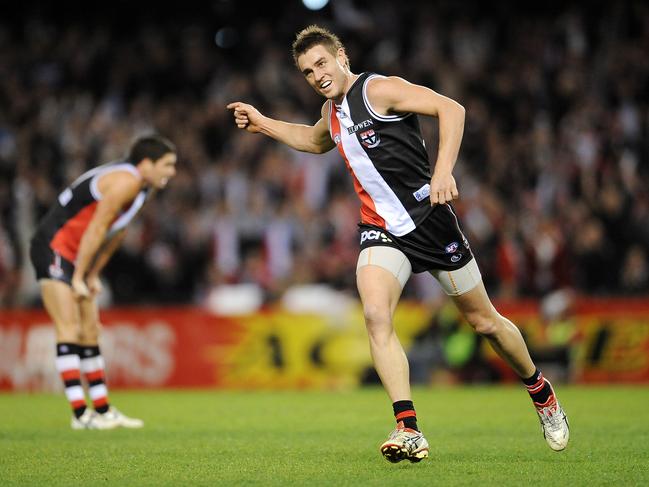

Fisher, the jailbird, will assume a role he would never have contemplated as he burst on the rebound in one of the three grand finals he played. Fisher has become a case study in how the transition from sporting star to has-been can go so wrong.

His tale has prompted a lot of hand-wringing within the football industry. Should there be more supports?

How do you help someone who refuses it? And, if Fisher had drug issues while he was still playing, how could they have remained a secret for so long?

Downward arc from decorated player to drug trafficker

Ex-football star doesn’t sit neatly with convicted drug trafficker.

For Fisher, as with Ben Cousins, the grubby details of the addiction seems so at odds with a player so blessed in verve and reliability.

Both players once oozed clear-eyed vitality on the park. Both, it turns out, defied systems of checks and balances to nurse double lives, each of which was in conflict with the other.

Fisher’s football triumphs, and their manner, confounds the understanding of his tale. Fisher prepared and prepared for every match. He prided himself on his readiness.

He credited his thoroughness for his successes. One imagines that he played every match, in all its infinite possibilities, in his mind long before he jogged on to the field.

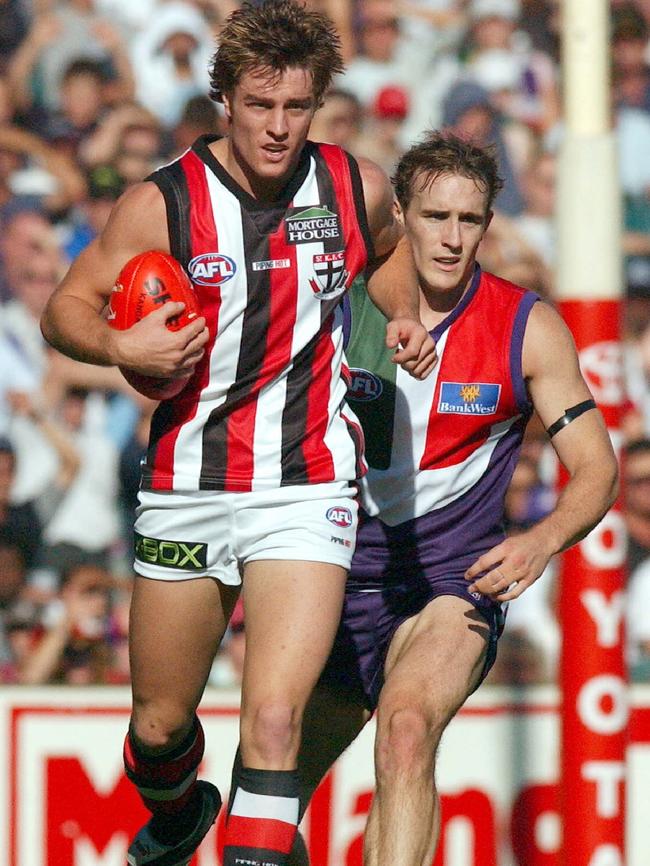

A long-time opponent, Geelong’s Cameron Mooney, serenaded Fisher’s career when it ended. He spoke of being embarrassed by Fisher’s “run and kicking” out of defence.

“I played on him a lot … ” Mooney said on radio.

“It was just great to play on him, it really was, because you just knew that you had a game on him every time.”

Reduced to a single word for his sporting prowess, the man himself chooses “reliable”.

Since football, Fisher has been unreliable.

He is going to jail because he picked up an oven rangehood from Harvey Norman in Moorabbin and delivered it to a nearby store connected to his trafficking accomplice.

When the rangehood, bound for Western Australia, was seized, it contained almost a kilogram of methamphetamine and 82 grams of cocaine.

A police search of his home turned up sizeable qualities of meth, LSD and other drugs.

His arrest, in May, 2022, may not have surprised those who knew Fisher well. Everyone else was caught out, even his parents in South Australia, who have since been emptied financially by their son’s legal bills.

He was tossed in jail, during Covid, and forced to withdraw from drugs in almost complete isolation.

The 43 days in jail was a “massive shock”.

There was no fresh air. He watched horse racing on the TV to pass the time. He walked slowly to and from prison phone calls to draw out the stimulation of this minor adventure.

He didn’t know how long he would be incarcerated. The lure of rehab – a notion it seems he had not really considered – beckoned if he could just get out of jail.

There, over the course of months, he discovered “emotions”.

“When I got to rehab, I didn’t really know what an emotion was,” he told a podcast last September.

“I had to get a chart printed off for me.”

He shared much of his story in the podcast, hosted by Shaun Wallis, of the Good Blokes Society.

The pair overlooked some of Fisher’s darker choices.

Relapses, for example, were not discussed – since being charged with drug trafficking, Fisher has also been fined for drug driving. Like all addicts, his toughest opponent lurks within.

Fisher instead spoke of his hopes for redemption. There was humour in his words, a country boy plainness which sounded unjaded by his experiences. He revealed a self-awareness that he did not possess until his life fell apart.

He was once the kid golfer, playing off scratch, who hoped to grow up and go pro. But he found he resented the forced solitariness of golf and its practice.

Footy clubs, in contrast, heaved with banter and united purpose.

The mateships and connections mattered to Fisher. He sounds as though he suffered for his removal from the environment and its “human connection”.

Fisher expressed guilt for his post-footy lifestyle. He had lacked courage, he said repeatedly, for not seeking help. Self-pity, if it was there, was masked by his stated desire to help others who stumble with drugs.

“If I can try and help someone that’s maybe in my position but before it gets too late (for them), that would be a really good feeling,” he said.

“To be able to turn this period of my life into a positive, hopefully there’s a silver lining under it. I think that there is and that’s me finding a new purpose, post footy, which I haven’t been able to do.”

His casting as a “cautionary tale” is a role he has tentatively tried to embrace.

The hard path, he learned from football, was about making good choices which did not necessarily feel pleasing – such as extra recovery sessions on a winter’s beach.

The easy path was sitting on the couch instead.

That’s how Fisher described his post footy choices. He forgot to be honest. He forgot the hard work. He forgot his mantra of “getting comfortable by being uncomfortable”.

There will be much discomfort in the coming months for Fisher, described by his former coach Ross Lyon as a “lovely person” with a “kind nature”.

“Drug trafficker” will soon sit alongside more pleasing labels, such as all-Australian player and twice St Kilda’s best and fairest.

A hard path, not of his choosing, awaits.

Perhaps he will draw on another of his footballing truisms which he offered, ironically, during an old interview in which he denied his drug problem: “I can control what I control and whatever happens outside I can’t control.”

These tiny changes appear in the brain before depression begins

More than 100 teenagers had their brain scans tracked throughout high school. The results could change our approach to depression.

Daughter breaks down in tearful mushroom trial testimony

The youngest daughter of Don and Gail Patterson wiped away tears as she recalled being at her dying parents’ bedsides in the days after the mushroom lunch. FOLLOW LIVE