Leyland P76: How a potential classic Aussie car was killed

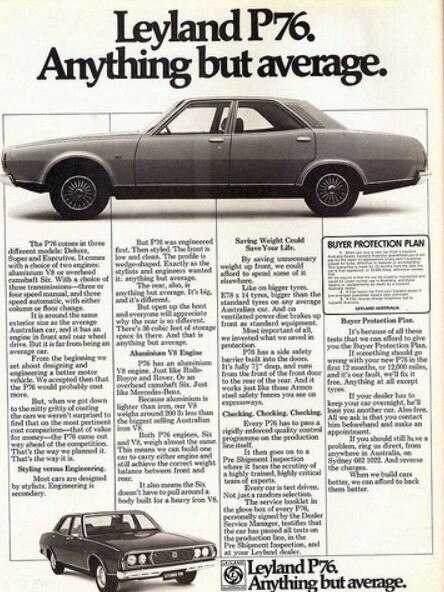

It was designed to be Australia’s best big car and blow away the Kingswood, Falcon and Valiant. But the innovative car instead became a national joke. So what went wrong?

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

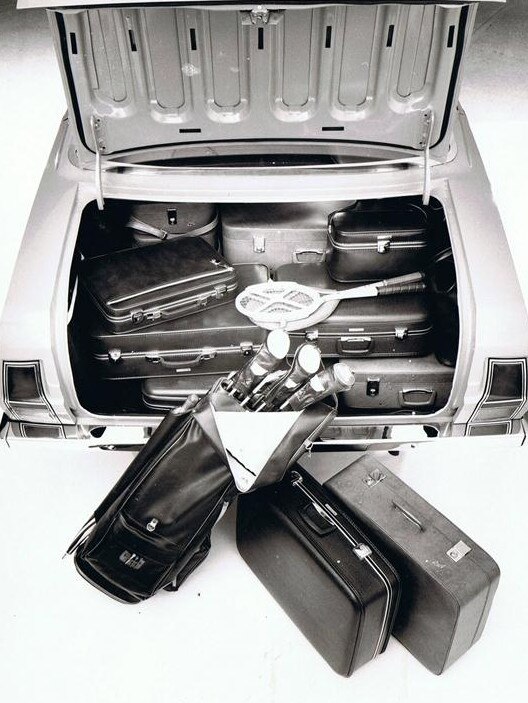

It may have had a boot large enough to hold a 44-gallon drum, but the Leyland P76 wouldn’t have sold any better if that expansive boot was stuffed with cash.

Leyland Australia’s great hope for grabbing a chunk of the nation’s lucrative family car market was tantalisingly close to its goal, but it failed thanks to a horrible collision of external factors, and more than a few others of the company’s own making.

Some wags dubbed it the “P38”, because it was only half a car, but in some respects it was way ahead of the Ford Falcon, Holden Kingswood and Chrysler Valiant.

AUSTRALIA’S MOST INNOVATIVE CARS

HOW FORD LAUNCHED AUSTRALIA’S MUSCLE CAR ERA

THE CARS YOU NEVER KNEW AUSTRALIANS MADE

British Motor Corporation Australia, later renamed Leyland Australia, began work on its homegrown family car in 1969, only four years ahead of the launch.

Until then, it built smaller front-wheel drive cars for the Australian market. Its largest car was the Austin Tasman and Kimberley range, stretched from the UK Austin 1800 range and with a 2.2-litre six cylinder engine to compete with Holden, Chrysler an Ford.

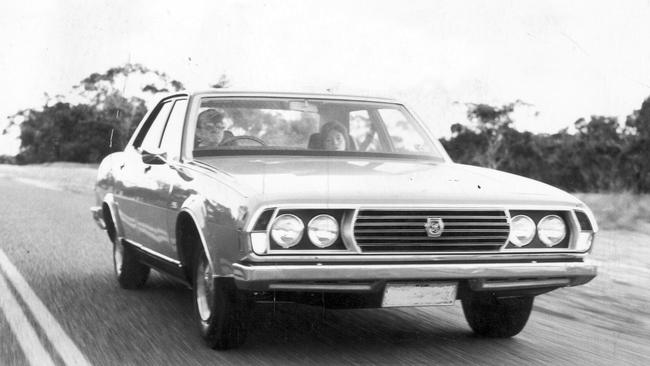

The Leyland P76, though, was to be a big, traditional rear-wheel drive car.

Dave Carey, a freelance writer who has penned a story about the troubled P76 project for Street Machine magazine this month, said problems set in right at the start, when

BMCA engineering director David Beech went to the company’s UK headquarters to fund the car’s development.

“Money was the problem from the start. David Beech went to his BMC overlords and said he’d need $30 million to pull this off — a realistic attack on the Aussie family car market — and he came back with $21 million, which is not a lot of money to build cars from scratch,” Carey said.

In today’s currency, Beech wanted just shy of $360 million to create a car from nothing. He walked away from headquarters with a tick over $250 million. By comparison, Chrysler Australia spent $22 million ($264 million today) to get its VH Valiant range to market in 1971, with an all-new body over existing mechanicals.

Beech was then faced withy the prospect of developing the car with no design studio to style the car and no proving ground to test its engineering.

He found a very sneaky way to get around the proving ground issue.

1976: WHEN AUSSIES DOMINATED THE AUSTRALIAN OPEN TENNIS

“They tested their vehicles under cloak and dagger by jamming their mechanicals under a bunch of Holdens. There were about 12, I think. It was pretty clever,” Carey said.

“There were varying amounts of Leyland technology underneath until the last one, which was a P76 underneath but an HK Kingswood on the outside.”

A wagon and a Monaro coupe were also used.

Leyland Australia planned a two-pronged attack on the Aussie car market with the smaller Morris Marina and the P76 family car.

The P76 was planned with the sedan, Force 7 couple and station wagon variants.

They enlarged the 2.2-litre Austin six to 2.6 litres and bored out a 3.5-litre V8 to 4.4 litres for the P76.

It was a bid to cut costs. Despite their similar looks, BMC’s Austin 1500, 1800, Tasman and Kimberley were costly to make because they did not share many parts. The Marina and P76 would change that, it was thought.

Carey said that although Giovanni Michelotti, a man associated with Ferrari, many sports cars and a range of BMC and Triumph models, was credited with designing the P76, it was almost entirely the work of Leyland Australia designer Romand Rodbergh.

Rodbergh, the Australian head of design, was overlooked by British Leyland as it sought a big name designer for the P76 project. Incensed, he sketched the eventual P76 while on holidays and submitted his design.

AUSSIE MUSCLE CARS PART TWO: HOW BROCK CHANGED EVERYTHING

It prevailed, but not before Michelotti spent a single week adding minor changes. Desperate for a big designer on which to market the car, Michelotti’s name stuck.

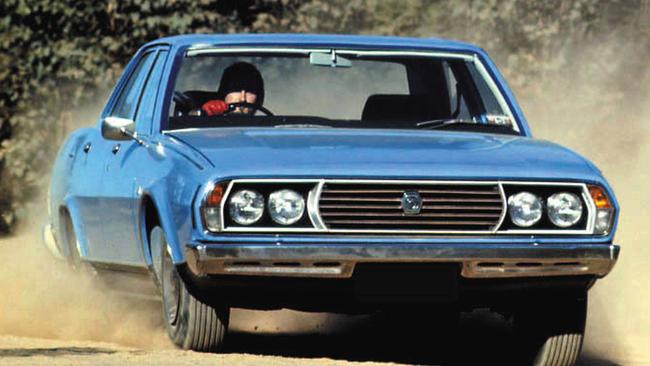

“It was a really futuristic design. It seems funny to say that now, but the design was a generation ahead of Ford and Holden. That squareness and wedginess of the P76 didn’t come to the fore until later in the ‘70s.”

Under the skin, there was a lot to like about the P76, starting with that huge boot.

It was the first car to offer front-wheel disc brakes on all models as standard, a much better system than the drum brakes still fitted to basic variants of the big three’s cars.

It included side intrusion bars for added crash safety years before these were mandated in Australian design rules, and it’s V8 was a winner.

“The V8 was all-alloy and it was super light for a V8 motor. I think there was only a few kilos’ difference between the V8 and Holden’s six. It was a larger motor. It was a lot lighter and it gave the car better ride and handling characteristics,” Carey said.

It was also the first Australian-built car with a bonded windscreen — glued into place to greatly enhance the strength and structural integrity of the roof and A-pillars. It was 15 years before Holden and Ford caught on.

Beech had German manufacturer Karmann in mind to construct tooling — machinery to stamp the P76’s panels and chassis — but Carey said this crucial aspect of production was compromised.

He said when it came time to produce the tooling, Karmann asked for a delay. Leyland was not prepared to alter its schedule and the job went to BMC-owned Press Steel-Fisher instead.

“But they had never worked on a big car before, Carey said.

“The P76’s bonnet was in one piece and was the biggest panel ever stamped it Australia at the time,” he said.

“There were problems with the tooling. It was done with substandard equipment and the A-pillars, the pillars on the side of your windscreen, would be drawn back and misshaped when they were attached to the roof.”

HOW TO DRIVE LIKE A MELBURNIAN

Poor tooling caused panels to fit badly all over the car.

To make matters worse, the production line, designed for those smaller Austin cars, was too narrow for the P76 to go down.

Carey said a press photo from the time showed a coupe with an obvious dent from the production line.

Many of the workers at Leyland’s Zetland plant in Sydney did not speak English and were unskilled.

“There were a lot of language issues because there were a lot of people there that were very new to Australia and were probably being taught by people who were patient enough either, at least initially,” Carey said.

“At first, they offered free English classes for the workers but they were fresh off the boat, they just wanted to get to work and start building a new life, and some of them culturally found it quite confronting to be in a classroom. Nobody showed up to the classes, so they ended up employing a gregarious Australian larrikin to teach these guys English as they worked.

“So they probably learned ‘door’ or ‘windscreen’ and 47 swear words because of the environment they were in, but not a lot else.”

DRIPPING, TELEDEXES: LONG LOST AUSSIE HOUSEHOLD ITEMS

Those slightly misshapen A-pillars and poor training combined to another issue — badly fitted bonded windscreens.

“Because the windscreens were glued in, there were no rubbers to absorb that distorted shape, and the workers weren’t well trained and didn’t put glue on all four sides, so the windscreens fell out or cracked, and it caused dust and water sealing issues.

“The only way to fix the problems was to put the cars back through the line, and that caused a lot of production delays and hurt sales.”

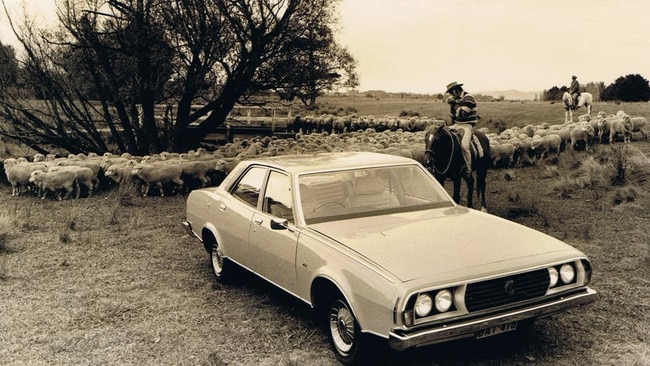

The P76 was unveiled to the public in June 1973.

By then, both Leyland Australia and British Leyland were drowning in debt.

Management had little choice but to offer for sale the flawed early cars it had already built.

The base model Deluxe started at $3250 ($30,770 today), with the 2.6-litre six and a three-speed column shift manual transmission.

An extra $180 would buy you the V8. Four on the floor cost $160, an automatic was an extra $250 and a luxury pack with bucket seats, a console with armrest, carpets and lighting for your glovebox, ashtray and under the bonnet was $98 more.

In September 1973, Wheels took a P76 Deluxe on a 4500km comparison test drive with the base model Falcon, Kingswood and Valiant.

Although its smaller engine was slightly down on performance, Wheels gave the P76 big ticks for its front disc brakes, its ride and handling, its interior comfort and its fuel economy.

“Clearly, P76 is right in there and capable of taking on the others. There are still rough edges to iron out and it doesn’t really live up to the European image bit, and we might wish for more power, but as a first effort in this class it works surprisingly well,” it said.

But cracks were showing. Test drivers noted the poor fit and finish of panels and exterior detailing, and the car was overheating through a mountain stretch of the 4500km test route.

The magazine later — and infamously — awarded its coveted Car of the Year award to the V8 version of the P76.

But the large car market in Australia was shrinking.

“The year before the P76 appeared on the market, Holden sales were down 12 per cent and Ford were down 7 per cent. People were still buying Holdens and Fords but people’s tastes were changing. They were buying Datsuns and Toyotas with better quality,” Carey said.

FUNKY SQUAD: VICTORIA POLICE IN THE 1970s

And then the first fuel crisis hit in 1973 as OPEC nations restricted supply and forced up fuel prices, in turn forcing more motorists to go smaller.

The P76’s quality bugbears and warranty claims were starting to hurt sales and Leyland Australia’s bottom line.

Cheap supplied components including dashboard knobs and switches, window winders and gear sticks, broke regularly.

Water and dust leaks from the bonded windscreens were widely reported.

Rattles and noises in the body and interior fittings such as the dashboards and consoles demonstrated the lack of proving ground testing.

Production delays plagued the factory because of strikes affecting components suppliers and demands from the big three that components they shared with Leyland for the P76 should go to Ford, Holden and Chrysler first.

It forced Leyland to stockpile mostly completed cars, again hurting sales because they could not supply cars to their dealers.

“You can’t deliver a car and say that we’ll send you those missing parts in a couple of weeks, so those cars had to wait around until the components could be sent,” Carey said.

Management in Sydney was denied the millions needed to invest in enlarging the production line but established a separate Rectification Centre, staffed by 60 of the Zetland plant’s best and brightest, to address quality issues and make the cars fit for sale.

END OF THE FORD FALCON ‘LIKE LOSING A FRIEND’

“Pretty much every car had to go through the Rectification Centre,” Carey said.

“That stuff eventually got rectified, but it created a reputation that was hard to get past.”

The company did a special run of 500 sporty Targa Florio sedans to celebrate the car’s win in a special stage of the 1974 World Cup Rally, a run from London to Munich through Spain, the Sahara Desert, Sicily, the Balkans and Turkey.

Drivers Evan Green and John Bryson won the special stage at the Targa Florio racing circuit in Sicily.

Targa Florio P76s came in three colours with special striping, alloy wheels, a sports steering wheel and the V8 engine.

It came late in the production run.

British Leyland pulled the plug on the P76 and the Zetland plant in October 1974.

Hundreds of jobs were lost at Zetland.

“People, when they malign the car, say the P76 really killed Leyland in Australia, but Leyland closed plants all over the world at the same time,” Carey said.

“They had plants in Spain, Italy and South Africa that closed at the same time, and there was a three-month coal strike in the UK that crippled a lot of companies, including Leyland. That wasn’t ideal for Leyland Australia.”

1970s: AUSTRALIA’S DECADE OF DISASTER

Carey said it’s rumoured up to 120 Force 7 coupes in V8 and six-cylinder variants were constructed but all but 10 were crushed, cash-strapped Leyland Australia, keen to enhance their value for a factory closure auction by enhancing the car’s rarity.

Three wagon prototypes were also built.

One was dismantled by the company engineers after testing to assess the strength of the body.

One was crushed, and the third was used as a factory workhorse until it sold at the auction.

Now the only one of its kind, the P76 wagon was been restored by a collector.

In all, 18,007 P76s were built.

Since production ended, P76 owners clubs have sprung up around Australia and, for that small group prepared to put up the slings and arrows of P76 ownership and all the jokes about the car, they remain highly prized.

But the P76 was always doomed, Carey said.

“All the planets needed to align but Leyland had a 56-planet solar system, and none of the planets aligned,” he said.

“The P76 had an endless stream of issues.

“Leyland put a lot of economic research into it but I think they misread the market and they were probably a bit enthusiastic about what they could pull off with the money they had.

“They entered a shrinking market. They only started designing the car in 1969, which is pretty late for a car they released only four years later, then 1972 was a bad year for the big three and then the fuel crisis hit.”

Read Dave Carey’s full story in the April edition of Street Machine.

Connect with Dave via his Facebook page, Garage of Awesome.